So many of you have asked how it went last night, I thought I’d try to give you my take on it, right here.

In a nutshell, it went very well.

After working for days (sweating, obsessing, etc) on my Powerpoint presentation, Isabel forced me (don’t ask me exactly how) to redo the whole thing yesterday morning before she left for work. Isabel is a really skilled speaker, and she’s developed a style for “inspirational” talks that make intellectual and scientific points digestible, entertaining, accessible, and potent. I’m just a stodgy old academic, so I still tend to put a lot of text on my slides. Trying to make sure I cover everything and include the necessary facts and figures, even at the risk of boring or losing some of my audience. So…I’ve learned enough to do what she says.

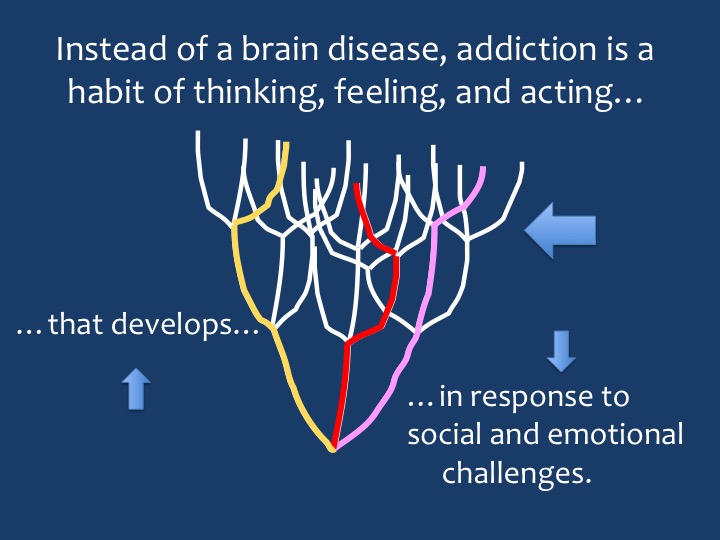

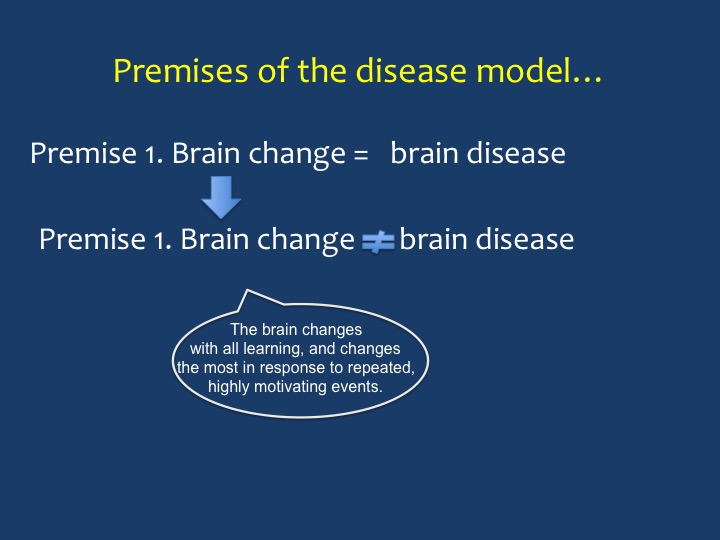

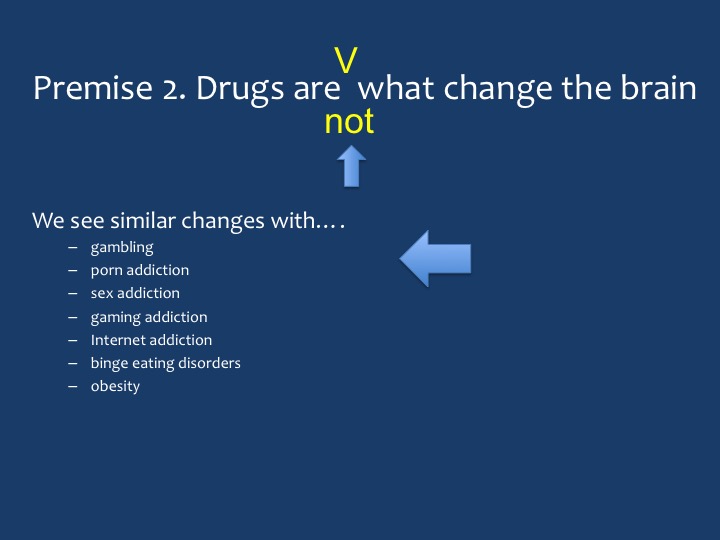

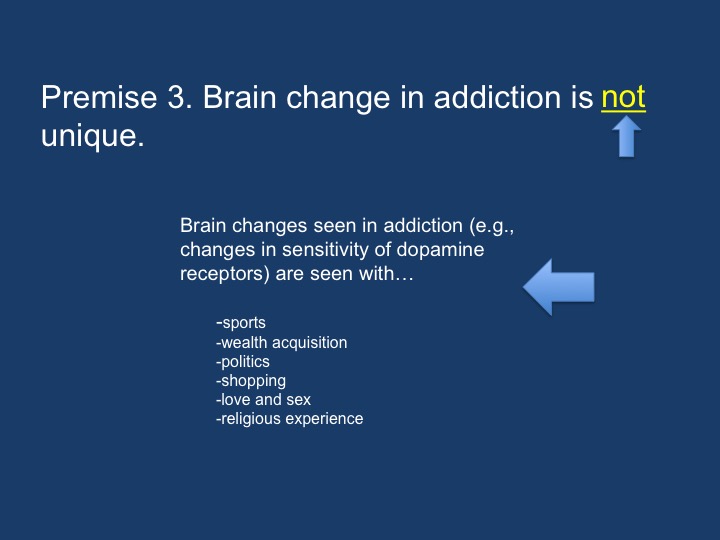

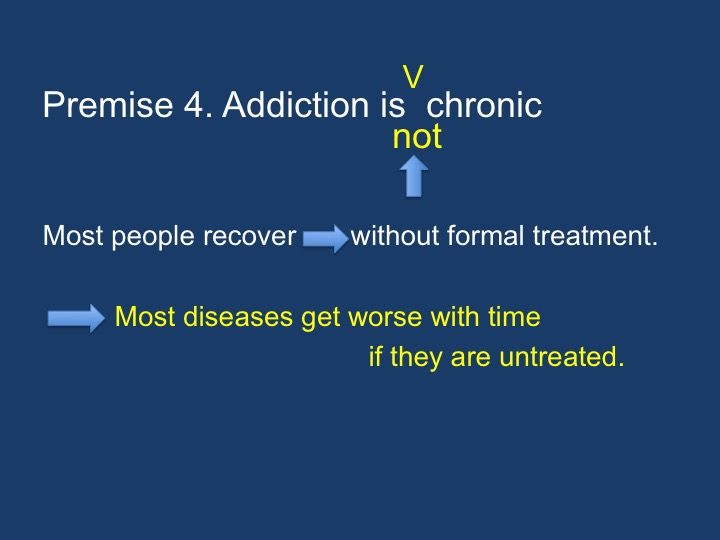

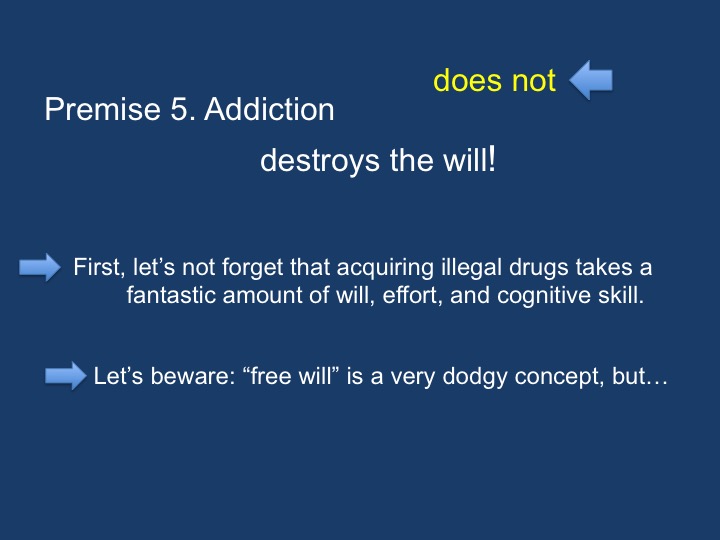

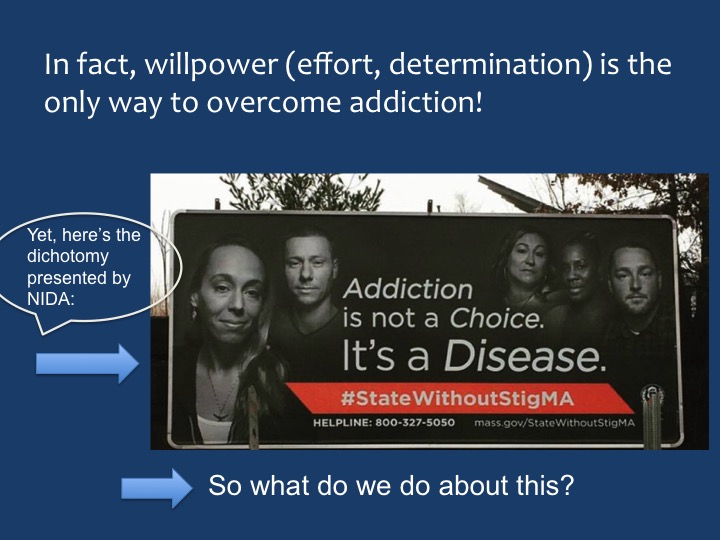

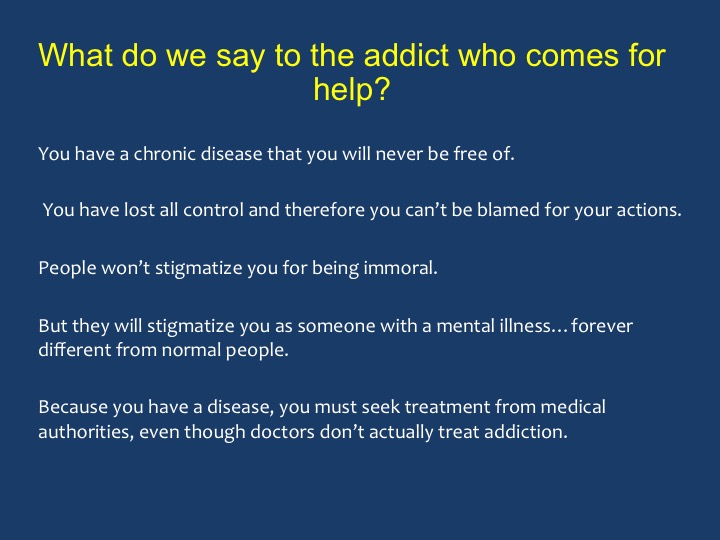

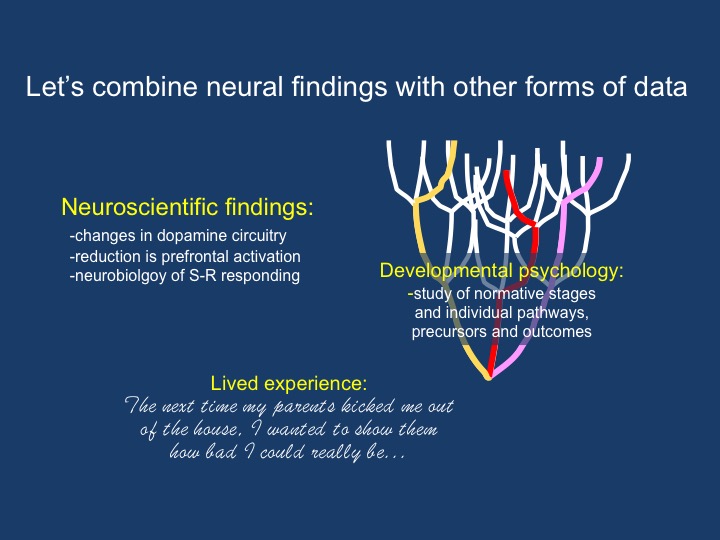

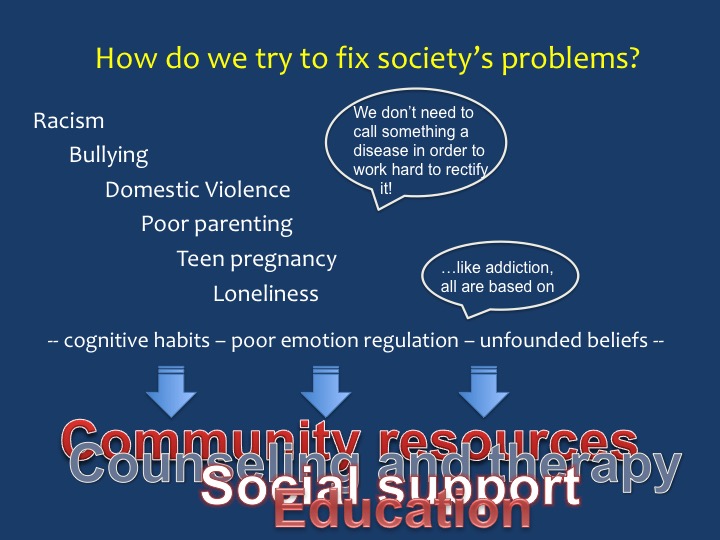

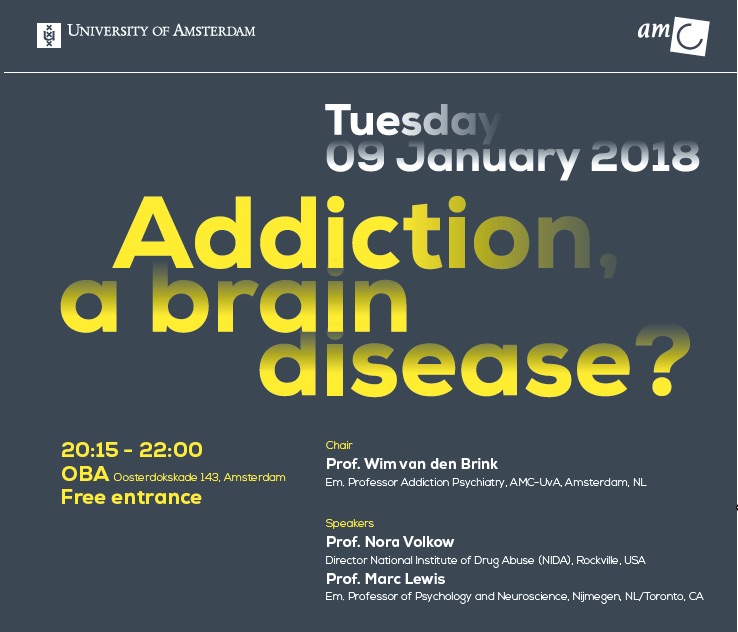

It took the whole day, but I finally got it done: a lean, mean, presentation. Slides with few words, mostly titles and bullet points, lots of cool animation, and a step-by-step breakdown of what the “disease model” of addiction gets wrong (in my opinion) and how to adapt/replace it with a more effective way to understand addiction and help those who suffer. I’ve printed all my slides below.

It took the whole day, but I finally got it done: a lean, mean, presentation. Slides with few words, mostly titles and bullet points, lots of cool animation, and a step-by-step breakdown of what the “disease model” of addiction gets wrong (in my opinion) and how to adapt/replace it with a more effective way to understand addiction and help those who suffer. I’ve printed all my slides below.

We were almost late and…there was a certain amount of anxiety involved. Parking in a highly questionable spot, racing through the train station to platform 11. Isabel had generously offered to go with me, essentially to hold my hand. I was kind of nervous but not too bad. And somewhat magically, the nervousness just evaporated when we got on the train.

I edited my slides obsessively during the trip, hardly noticed changing trains in Utrecht, and I babbled to myself all the way. What might Nora Volkow say to this, and to that, and did it matter? And how to deliver what I needed to deliver without being overbearing or attacking or…too wimpy.

It was a cold night in Amsterdam, but everything glittered: the magnificent structures of the old city interspersed with modern buildings that were also imaginative and beautiful in their own way. All of it reflected off the canals. We found the venue, about a ten-minute walk from the station: a beautiful and very modern library, and in it a classy theater that could seat about 250. Isabel looked fabulous. I looked dowdy. I guess we averaged out okay.

It was a cold night in Amsterdam, but everything glittered: the magnificent structures of the old city interspersed with modern buildings that were also imaginative and beautiful in their own way. All of it reflected off the canals. We found the venue, about a ten-minute walk from the station: a beautiful and very modern library, and in it a classy theater that could seat about 250. Isabel looked fabulous. I looked dowdy. I guess we averaged out okay.

So…there was Nora Volkow, in the flesh, We had a friendly enough greeting. She was there to receive an honorary PhD from the University of Amsterdam. I asked her how many PhDs she had now. She said she truly didn’t know. She is the most renowned and probably the busiest addiction scientist in the world. She’s earned her stripes. But of course she’s just a person, looking a bit tired and no doubt jet-lagged on this particular night.

So…there was Nora Volkow, in the flesh, We had a friendly enough greeting. She was there to receive an honorary PhD from the University of Amsterdam. I asked her how many PhDs she had now. She said she truly didn’t know. She is the most renowned and probably the busiest addiction scientist in the world. She’s earned her stripes. But of course she’s just a person, looking a bit tired and no doubt jet-lagged on this particular night.

By the time we started, the theater was completely packed. She got up on the stage and did her thing: energetic, committed, sure of herself, convinced that neuroscience was the main act when it comes to understanding addiction. She showed some colourful brain MRIs, talked about dopamine a lot, and…well if you want to know more about her message, go to the NIDA website.

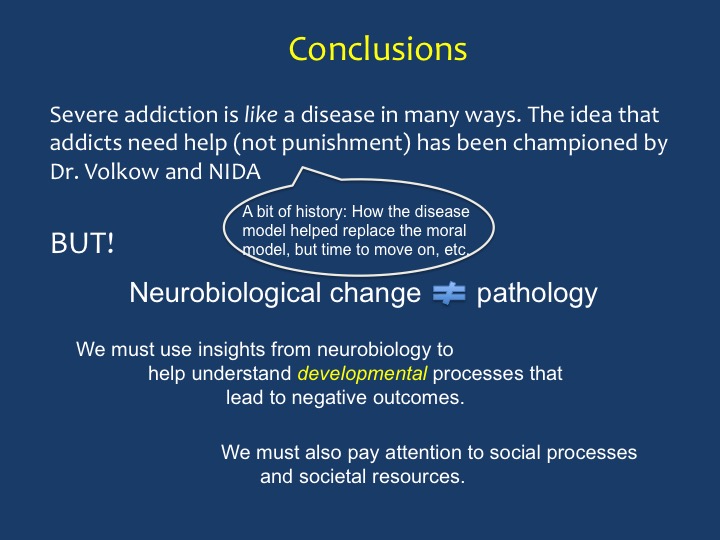

One thing that did impress me (and others) was that she talked a bit about recovery from addiction. For many years, the NIDA party line has been that addiction is a chronic brain disease. People don’t recover from chronic diseases. So…maybe that’s progress. Maybe the addiction neuroscientists are starting to listen to our messages about the experience of addiction, its developmental time course, the enormous individual differences in process and outcome, the gradations in levels of intensity…and the very important issue of free will — something that Nora has long claimed gets wiped out by drugs. The hijacked brain. In my talk I emphasized that addicts do not lose their willpower — in fact they have a great deal of it. Rather, they have a hard time making choices that are good for them in the long run. And choice is not a simple thing — for anybody.

Maybe the brain scientists, including Nora Volkow, are tuning into the personal and social and societal foundations of addiction. I hope so, and I hope that those in the “psychosocial” camp start listening to the brain scientists as well. These are all pieces of the same puzzle.

Nora talked for about 20 minutes, then I went up there and did my spiel. It was a good talk. If I was a religious person, I’d say the power moved in me…or something like that. I was hardly conscious of what I was saying. It was that thing they call “flow.” But man, it felt good, because I could tell it was coming out just right, and Isabel sat in the third row and smiled hugely every time we made eye contact. And then, lots of applause — especially for the Dutch — and then a debate between Nora and me with input from a panel of three experts and the audience.

And so on and so forth. I won’t try to capture any more of it for now. The evening was recorded, and I think the talks and debate will all show up on YouTube before long. I’ll let you know.

Meanwhile, here are my slides. I’ve inserted blue arrows to try to give you a sense of what words and images appeared partway through the slides (via animation). I’ve also included some “speech balloons” to approximate the things I said that don’t appear on the slides. A lot is missing, I know. As per Isabel’s instructions, there was less to read and more just to speak.

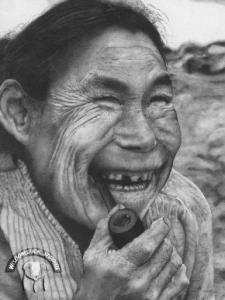

of ice. When spring arrives, it is of no use to try to clear it up all at once. The only thing to do is to let each layer appear one after another as the higher chunk thaws. So one layer thaws and is cleared away, then another, then another. No one can force their way prematurely to the bottom of the heap, but they can rest assured that every layer will finally be revealed and dealt with.

of ice. When spring arrives, it is of no use to try to clear it up all at once. The only thing to do is to let each layer appear one after another as the higher chunk thaws. So one layer thaws and is cleared away, then another, then another. No one can force their way prematurely to the bottom of the heap, but they can rest assured that every layer will finally be revealed and dealt with. This parable corresponds beautifully with the Inuit concept of time. I have come to understand this. From the birth of man and consciousness, in earlier agricultural societies, time was circular. The rhythm of life was cyclical, from the beginning of life in spring through growth, harvest and finally death. Death was followed by rebirth, for nature and for man. The cycle would start all over again. The industrial revolution changed our concept of time, nature did not dictate it any more, but production lines did. Time became linear, just like production and progress. Peak performance was always in demand. Be productive! Act now! Consume now! Be happy now! And be greedy!

This parable corresponds beautifully with the Inuit concept of time. I have come to understand this. From the birth of man and consciousness, in earlier agricultural societies, time was circular. The rhythm of life was cyclical, from the beginning of life in spring through growth, harvest and finally death. Death was followed by rebirth, for nature and for man. The cycle would start all over again. The industrial revolution changed our concept of time, nature did not dictate it any more, but production lines did. Time became linear, just like production and progress. Peak performance was always in demand. Be productive! Act now! Consume now! Be happy now! And be greedy! The old Inuit concept of time sees no time spent, no time wasted, no time gone. Time arrives. Time only arrives. Each and every moment we receive the gift of time to be added to all the gifts of time already received. Yes, nature is cyclical, yet still unpredictable; the variations in weather, the movements of the sea animals and of the ice are never exactly the same. Nature asks of you only attention and time.

The old Inuit concept of time sees no time spent, no time wasted, no time gone. Time arrives. Time only arrives. Each and every moment we receive the gift of time to be added to all the gifts of time already received. Yes, nature is cyclical, yet still unpredictable; the variations in weather, the movements of the sea animals and of the ice are never exactly the same. Nature asks of you only attention and time. change what all this means to me now. I have gained an insight that I would almost call spiritual, where even my ancestors and the story of my extended and immediate family belong. And where all of you (in this community) belong. Instead of disconnection there is now connection, over space and over time. There is, in each moment, attention, time and power to grow.

change what all this means to me now. I have gained an insight that I would almost call spiritual, where even my ancestors and the story of my extended and immediate family belong. And where all of you (in this community) belong. Instead of disconnection there is now connection, over space and over time. There is, in each moment, attention, time and power to grow.

control. I had people coming up to me while I stood rigid, paralyzed, in the middle of a busy hotel lobby between session, and carry or drag me to the nearest sofa (it was a pretty plush hotel). And even sitting, I could not unspasm; my body seemed like a lighting rod that would not stop zapping. People I didn’t know — strangers — found me a wheelchair, wheeled me to the elevator, got me down to the street level and called a taxi to take me to the hospital. And the next day, at a doctor’s office near my own hotel, I was howling so bad that the doctor and his assistants dragged me out of the waiting room because I was scaring the other patients. They then lifted me into a taxi — back to the hospital again. When all I really needed was a shot of morphine or a substantial dose of oxycodone. Getting high was the furthest thing from my mind.

control. I had people coming up to me while I stood rigid, paralyzed, in the middle of a busy hotel lobby between session, and carry or drag me to the nearest sofa (it was a pretty plush hotel). And even sitting, I could not unspasm; my body seemed like a lighting rod that would not stop zapping. People I didn’t know — strangers — found me a wheelchair, wheeled me to the elevator, got me down to the street level and called a taxi to take me to the hospital. And the next day, at a doctor’s office near my own hotel, I was howling so bad that the doctor and his assistants dragged me out of the waiting room because I was scaring the other patients. They then lifted me into a taxi — back to the hospital again. When all I really needed was a shot of morphine or a substantial dose of oxycodone. Getting high was the furthest thing from my mind. So why couldn’t they provide that? Even at the hospital, I had to lie on a gurney intermittently screeching in pain for over an hour before the morphine came. People passing by had pity written all over their faces. Has the opioid scare infested Europe too? Not as much as the US, but yes, seemingly, to a degree.

So why couldn’t they provide that? Even at the hospital, I had to lie on a gurney intermittently screeching in pain for over an hour before the morphine came. People passing by had pity written all over their faces. Has the opioid scare infested Europe too? Not as much as the US, but yes, seemingly, to a degree. from that kind of pain as well. But of course no doctor will prescribe opioids for your depression, unless you’re getting methadone or Suboxone because you’re a “registered” addict, whatever that happens to mean in your corner of the world. Maybe just lining up at some seedy clinic, maybe being sneered at, maybe not being able to get a job, maybe having your license revoked…hell, in the Philippines it means being lined up and shot.

from that kind of pain as well. But of course no doctor will prescribe opioids for your depression, unless you’re getting methadone or Suboxone because you’re a “registered” addict, whatever that happens to mean in your corner of the world. Maybe just lining up at some seedy clinic, maybe being sneered at, maybe not being able to get a job, maybe having your license revoked…hell, in the Philippines it means being lined up and shot. When we’re in that kind of pain, and if we’re pretty sure that opioids can help relieve it, we’re trapped. We can’t get an opioid prescription for emotional relief. (Don’t get me started on “antidepressants” — SSRIs — which are so much less effective than hoped, which carry their own batch of side effects, and which require as much tapering as opioids to minimize withdrawal symptoms.) So we buy, borrow, steal, forge, or do whatever we have to do to acquire the medication that can bring us back to some semblance of normality, of peace.

When we’re in that kind of pain, and if we’re pretty sure that opioids can help relieve it, we’re trapped. We can’t get an opioid prescription for emotional relief. (Don’t get me started on “antidepressants” — SSRIs — which are so much less effective than hoped, which carry their own batch of side effects, and which require as much tapering as opioids to minimize withdrawal symptoms.) So we buy, borrow, steal, forge, or do whatever we have to do to acquire the medication that can bring us back to some semblance of normality, of peace.