…by Hanna Pickard…

Hanna is one of several addiction researchers who wrote commentaries about my book and my theory of addiction. Here she explains how we can view addiction as guided by choice without the extra baggage of blame, shame, and stigma. Following are segments of her revised commentary, which can be seen in full here.

Hanna is one of several addiction researchers who wrote commentaries about my book and my theory of addiction. Here she explains how we can view addiction as guided by choice without the extra baggage of blame, shame, and stigma. Following are segments of her revised commentary, which can be seen in full here.

Hanna and I have discussed her viewpoint in detail, and we are largely in agreement. However, she sees me as rejecting a “choice” model of addiction. I don’t agree with that. I think that addicts do have choices, but they are not simple choices. They are difficult, effortful choices to struggle against years of habit formation and the conditioning that goes with it — especially since habitual behaviours become wired in our brains, at least for a while. This makes choice difficult — but certainly not impossible.

Despite our disagreement about what I think of choice, Hanna’s essay makes some excellent points. Here’s what she has to say —

……………………….

Drug use and drug addiction are severely stigmatised around the world. Cross-cultural studies suggest that social disapproval of addiction is greater than social disapproval of a range of highly stigmatised conditions, including leprosy, HIV, homelessness, dirtiness, neglect of children, and a criminal record for burglary… Our common language also expresses stigma: people who use drugs are “junkies”, mothers who use drugs are “crack moms”, and abstinence is called “getting clean” — implying, of course, that when people use drugs they are dirty…

Why are drug users and addicts subjected to stigma and harsh treatment? No doubt a full explanation depends on a variety of complicated historical, socio-political and economic forces. But…we must also recognise how much these attitudes and policies resonate with the moral model of addiction which was dominant in the first half of the Twentieth Century.

The moral model of addiction has two distinctive features. First, it views drug use as a choice, even for addicts. Second, it adopts a critical moral stance against this choice. Addicts are considered people of  bad character with antisocial values: selfish and lazy, they supposedly value pleasure, idleness and escape above all else, and are willing to pursue these at any cost to themselves or others. In contemporary Western culture, we typically hold people responsible for actions if they have a choice and so could do otherwise, and we excuse people from responsibility if they don’t. Because the moral model of addiction sees drug use as a choice, it views addicts as responsible — deserving of the stigma and harsh treatment they in fact receive.

bad character with antisocial values: selfish and lazy, they supposedly value pleasure, idleness and escape above all else, and are willing to pursue these at any cost to themselves or others. In contemporary Western culture, we typically hold people responsible for actions if they have a choice and so could do otherwise, and we excuse people from responsibility if they don’t. Because the moral model of addiction sees drug use as a choice, it views addicts as responsible — deserving of the stigma and harsh treatment they in fact receive.

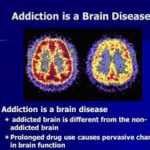

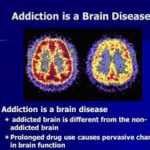

For those who recoil from the attitudes embodied in the moral model, the disease model of addiction can appear by contrast to offer a desperately needed [alternative]. “When addiction specialists say that addiction is a disease, they mean that drug use has become involuntary.” According to the disease model, addiction is a chronic, relapsing neurobiological disease characterised by compulsive use despite negative consequences. Repeated drug use is supposed to change the brain so as to render the desire for drugs irresistible: the disease model maintains that addicts literally cannot help using drugs and have no choice over consumption.

For those who recoil from the attitudes embodied in the moral model, the disease model of addiction can appear by contrast to offer a desperately needed [alternative]. “When addiction specialists say that addiction is a disease, they mean that drug use has become involuntary.” According to the disease model, addiction is a chronic, relapsing neurobiological disease characterised by compulsive use despite negative consequences. Repeated drug use is supposed to change the brain so as to render the desire for drugs irresistible: the disease model maintains that addicts literally cannot help using drugs and have no choice over consumption.

I agree with Lewis that addiction is not a disease — at least given the typical meaning and implications of that concept. And I believe Lewis is correct to emphasise the central importance of a sense of agency, empowerment, and personal growth and self-understanding, in overcoming addiction. But I do not agree [with Lewis] that we must reject a choice model of addiction.

There are two straightforward reasons why. The first is that the evidence is ever-increasing that, however hard it is for addicts to control their use, and however important it is for others to recognize and respect this struggle, addicts…have choice over their consumption in many circumstances. To briefly review some of this evidence: Anecdotal and first-person reports abound of addicts (including those with a DSM-based diagnosis of dependence) going “cold turkey”. Large-scale epidemiological studies demonstrate that the majority of addicts “mature out” without clinical intervention in their late twenties and early thirties, as the responsibilities and opportunities of adulthood…increase.  Experimental studies show that, when offered a choice between taking drugs or receiving money then and there in the laboratory setting, addicts will frequently choose money over drugs. Finally, since Bruce Alexander’s seminal experiment “Rat Park” first intimated that something similar might be true of rats, animal research on addiction has convincingly demonstrated that…cocaine-addicted rats will…forego cocaine and choose alternative goods, such as saccharin or same-sex snuggling, if available. In short, the evidence is strong that drug use in addiction is not involuntary: addicts are responsive to incentives and so have choice and a degree of control over their consumption in a great many circumstances.

Experimental studies show that, when offered a choice between taking drugs or receiving money then and there in the laboratory setting, addicts will frequently choose money over drugs. Finally, since Bruce Alexander’s seminal experiment “Rat Park” first intimated that something similar might be true of rats, animal research on addiction has convincingly demonstrated that…cocaine-addicted rats will…forego cocaine and choose alternative goods, such as saccharin or same-sex snuggling, if available. In short, the evidence is strong that drug use in addiction is not involuntary: addicts are responsive to incentives and so have choice and a degree of control over their consumption in a great many circumstances.

The second reason to maintain a choice model of addiction is that the process of overcoming addiction through a sense of agency, empowerment, and personal growth and self-understanding — a process that Lewis describes in The Biology of Desire with great care and acuity — itself presupposes that addicts have choice and a degree of control. Agency needs to exist to be mobilized: you can only decide to quit and do what it takes to stop using and change how you live and the kind of person you are if you have some choice and control over your use and your identity.

The second reason to maintain a choice model of addiction is that the process of overcoming addiction through a sense of agency, empowerment, and personal growth and self-understanding — a process that Lewis describes in The Biology of Desire with great care and acuity — itself presupposes that addicts have choice and a degree of control. Agency needs to exist to be mobilized: you can only decide to quit and do what it takes to stop using and change how you live and the kind of person you are if you have some choice and control over your use and your identity.

Recall that the moral model of addiction has two features. It views drug use as a choice. And it adopts a critical moral stance against this choice. Because of the evidence [just reviewed], I believe we must accept the first feature. But that does not mean we must also accept the second. Just as addicts have choices with respect to drug use, we have choices with respect to how we respond to people who use drugs.

Marc Lewis has diagnosed a genuine dilemma: the disease model is neither credible in the face of the evidence nor helpful in so far as it disempowers addicts; but…a choice model invites blame and stigma by attributing agency and responsibility to addicts. In response, he has opted to distance himself from both. But that is an unstable position… We must accept a choice model of addiction – although [we also] need to contextualise choices and understand the variety of ways control, agency, and so too responsibility, may be reduced in addiction.

However, accepting a choice model of addiction incurs a moral burden… Choice models of addiction ought…to be paired with a practice of [questioning] our own attitudes towards addiction alongside a commitment to working for social justice. [It is possible to distinguish] our concept of responsibility from our concept of blame.

Suppose we begin by asking a direct question to challenge the moral model: What precisely is supposed to be wrong with using drugs? Throughout human history, drugs have been used as means to achieve a host of valuable ends, including (1) improved social interaction; (2) facilitated mating and sex; (3) heightened cognitive performance; (4) facilitated recovery and coping with stress; (5) self-medication for negative emotions, psychological distress and other mental health problems and symptoms; (6)  sensory curiosity – expanded experiential horizon; and, finally, (7) euphoria and hedonia – in other words, pleasure. Drugs make us feel good, provide relief from suffering, and help us do various things we want to do better. [It] is difficult to see what could possibly be wrong with using drugs in and of itself. Suppose now we ask a further direct question: When use escalates to the point of addiction, who is to be held responsible for the ensuing negative consequences? According to the moral model, it is addicts themselves, who are not only responsible but [blameworthy], as they are considered to be fundamentally people of bad character with antisocial values… As an advocate of a choice model of addiction, I do not of course deny that some responsibility — but, crucially, responsibility as distinct from blame — lies with addicts themselves… The point I wish to emphasise however is that, in placing blame squarely on addicts or their disease, both models are united in enabling us to keep the focus of our attention away from ourselves and our society, avoiding the question of whether we, as a society, also collectively bear some responsibility for drug use and addiction and their consequent harms.

sensory curiosity – expanded experiential horizon; and, finally, (7) euphoria and hedonia – in other words, pleasure. Drugs make us feel good, provide relief from suffering, and help us do various things we want to do better. [It] is difficult to see what could possibly be wrong with using drugs in and of itself. Suppose now we ask a further direct question: When use escalates to the point of addiction, who is to be held responsible for the ensuing negative consequences? According to the moral model, it is addicts themselves, who are not only responsible but [blameworthy], as they are considered to be fundamentally people of bad character with antisocial values… As an advocate of a choice model of addiction, I do not of course deny that some responsibility — but, crucially, responsibility as distinct from blame — lies with addicts themselves… The point I wish to emphasise however is that, in placing blame squarely on addicts or their disease, both models are united in enabling us to keep the focus of our attention away from ourselves and our society, avoiding the question of whether we, as a society, also collectively bear some responsibility for drug use and addiction and their consequent harms.

Do we collectively bear such responsibility? …A disproportionate number of addicts come from underprivileged socioeconomic backgrounds, have suffered from childhood abuse and adversity,  struggle with mental health problems, and are members of minority ethnic groups or other groups subjected to prejudice and discrimination. They may experience extreme psychological distress alongside a host of mental health problems apart from their addiction, feel a lack of psychosocial integration, and are at a socioeconomic disadvantage such that they have severely limited

struggle with mental health problems, and are members of minority ethnic groups or other groups subjected to prejudice and discrimination. They may experience extreme psychological distress alongside a host of mental health problems apart from their addiction, feel a lack of psychosocial integration, and are at a socioeconomic disadvantage such that they have severely limited  opportunities. These circumstances are central to understanding addiction in many contexts. Put crudely, the reason is simply that drugs offer a way of coping with stress, pain, and some of the worst of life’s miseries, when there is little possibility for genuine hope or improvement… In such circumstances, whatever harms accrue from using drugs must be weighed against whatever harms accrue from not using them. For this reason, the explanation of addiction and its associated negative consequences must lie in no small part with the psycho-socio-economic circumstances that cause such suffering and limit opportunities. And the existence of these circumstances is a feature of our society for which we must all collectively take some responsibility.

opportunities. These circumstances are central to understanding addiction in many contexts. Put crudely, the reason is simply that drugs offer a way of coping with stress, pain, and some of the worst of life’s miseries, when there is little possibility for genuine hope or improvement… In such circumstances, whatever harms accrue from using drugs must be weighed against whatever harms accrue from not using them. For this reason, the explanation of addiction and its associated negative consequences must lie in no small part with the psycho-socio-economic circumstances that cause such suffering and limit opportunities. And the existence of these circumstances is a feature of our society for which we must all collectively take some responsibility.

Both the moral and the disease model of addiction can therefore be seen to function as a psychological defense — protecting us from focussing our attention on the existence of these circumstances and their role in explaining drug use and addiction, thereby keeping consciousness of our own collective responsibility for these facts at bay. Perhaps one reason, then, why we blame and stigmatise addicts for their choices is that it is more comfortable than facing up to aspects of our society which make drugs — whatever their costs — such a good option for many of our already vulnerable and disadvantaged members.

Note: Hanna will be talking about drugs and addiction on Radio 4 on Wednesday, 12 July, at 20:45 BST. (After that date, the broadcast will be available for download here.)

Why is it so hard? Why is there so much suffering, in the world, in ourselves? That question comes up all the time, especially among us addicts (recovered or not). We’re not the only ones. We just tried to find a way out through the back door. The proportion of people in the Western World (e.g., the US) who suffer from anxiety and/or depression (and related conditions) is astronomical. And for today’s young people it seems to be getting worse, though that conclusion is conflated with changes in the way people communicate with each other and with mental health professionals.

Why is it so hard? Why is there so much suffering, in the world, in ourselves? That question comes up all the time, especially among us addicts (recovered or not). We’re not the only ones. We just tried to find a way out through the back door. The proportion of people in the Western World (e.g., the US) who suffer from anxiety and/or depression (and related conditions) is astronomical. And for today’s young people it seems to be getting worse, though that conclusion is conflated with changes in the way people communicate with each other and with mental health professionals. One simple answer is that we evolved from physical matter to become the unfathomably sensitive and intelligent creatures we are. And evolution doesn’t concern itself with suffering. In fact suffering (struggle, loss, and death) is a big part of what drives it.

One simple answer is that we evolved from physical matter to become the unfathomably sensitive and intelligent creatures we are. And evolution doesn’t concern itself with suffering. In fact suffering (struggle, loss, and death) is a big part of what drives it. know, someone who has struggled on and off with addiction throughout his life. He told me of his childhood traumas and hardships, and of the brutal treatment received by his parents in an internment camp during World War II who, as a result, were never able to give him what he needed as a child. He sees himself as someone who has to struggle and persevere just to get through each day, fending off anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and meaninglessness — you know, the usual quartet of background singers.

know, someone who has struggled on and off with addiction throughout his life. He told me of his childhood traumas and hardships, and of the brutal treatment received by his parents in an internment camp during World War II who, as a result, were never able to give him what he needed as a child. He sees himself as someone who has to struggle and persevere just to get through each day, fending off anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and meaninglessness — you know, the usual quartet of background singers. present, accepting the ebb and flow of forces that sometimes bring happiness but undoubtedly bring suffering and lead, inevitably, to loss and death. And certainly these forces are intermingled with the disconnection, competition, and often cruelty that we face from other humans who are, when you stop and think about it, just as caught up in their own struggles to survive from day to day and hold onto a bit of happiness.

present, accepting the ebb and flow of forces that sometimes bring happiness but undoubtedly bring suffering and lead, inevitably, to loss and death. And certainly these forces are intermingled with the disconnection, competition, and often cruelty that we face from other humans who are, when you stop and think about it, just as caught up in their own struggles to survive from day to day and hold onto a bit of happiness. But there are other ways to think about it. Fairness is a construction we learn at around age five, and it has absolutely nothing to do with the natural universe. It’s just a social norm, a code for resolving petty rivalries. It’s no more relevant to nature than tea ceremonies or Facebook.

But there are other ways to think about it. Fairness is a construction we learn at around age five, and it has absolutely nothing to do with the natural universe. It’s just a social norm, a code for resolving petty rivalries. It’s no more relevant to nature than tea ceremonies or Facebook. In fact, we are lucky as hell to be here at all. And suffering is just part of the process that brought us here and that continues to give us the chance to evolve and, hopefully, to grow more intelligent, compassionate, and beautiful.

In fact, we are lucky as hell to be here at all. And suffering is just part of the process that brought us here and that continues to give us the chance to evolve and, hopefully, to grow more intelligent, compassionate, and beautiful. guy with Huntington’s Disease, a guy who is presently in the process of losing everything, his body and his mind. And he’s talking about connecting and accepting and loving. He’s nowhere close to despair. I’m only partway through and I can’t yet recommend it confidently, but take a look if you like. There are certainly gems of wisdom in the book, and even the fact that this guy can think this way and write this way is astonishing and uplifting.

guy with Huntington’s Disease, a guy who is presently in the process of losing everything, his body and his mind. And he’s talking about connecting and accepting and loving. He’s nowhere close to despair. I’m only partway through and I can’t yet recommend it confidently, but take a look if you like. There are certainly gems of wisdom in the book, and even the fact that this guy can think this way and write this way is astonishing and uplifting.

Hanna is one of several addiction researchers who wrote commentaries about my book and my theory of addiction. Here she explains how we can view addiction as guided by choice without the extra baggage of blame, shame, and stigma. Following are segments of her revised commentary,

Hanna is one of several addiction researchers who wrote commentaries about my book and my theory of addiction. Here she explains how we can view addiction as guided by choice without the extra baggage of blame, shame, and stigma. Following are segments of her revised commentary,  bad character with antisocial values: selfish and lazy, they supposedly value pleasure, idleness and escape above all else, and are willing to pursue these at any cost to themselves or others. In contemporary Western culture, we typically hold people responsible for actions if they have a choice and so could do otherwise, and we excuse people from responsibility if they don’t. Because the moral model of addiction sees drug use as a choice, it views addicts as responsible — deserving of the stigma and harsh treatment they in fact receive.

bad character with antisocial values: selfish and lazy, they supposedly value pleasure, idleness and escape above all else, and are willing to pursue these at any cost to themselves or others. In contemporary Western culture, we typically hold people responsible for actions if they have a choice and so could do otherwise, and we excuse people from responsibility if they don’t. Because the moral model of addiction sees drug use as a choice, it views addicts as responsible — deserving of the stigma and harsh treatment they in fact receive. For those who recoil from the attitudes embodied in the moral model, the disease model of addiction can appear by contrast to offer a desperately needed [alternative]. “When addiction specialists say that addiction is a disease, they mean that drug use has become involuntary.” According to the disease model, addiction is a chronic, relapsing neurobiological disease characterised by compulsive use despite negative consequences. Repeated drug use is supposed to change the brain so as to render the desire for drugs irresistible: the disease model maintains that addicts literally cannot help using drugs and have no choice over consumption.

For those who recoil from the attitudes embodied in the moral model, the disease model of addiction can appear by contrast to offer a desperately needed [alternative]. “When addiction specialists say that addiction is a disease, they mean that drug use has become involuntary.” According to the disease model, addiction is a chronic, relapsing neurobiological disease characterised by compulsive use despite negative consequences. Repeated drug use is supposed to change the brain so as to render the desire for drugs irresistible: the disease model maintains that addicts literally cannot help using drugs and have no choice over consumption. Experimental studies show that, when offered a choice between taking drugs or receiving money then and there in the laboratory setting, addicts will frequently choose money over drugs. Finally, since Bruce Alexander’s seminal experiment “Rat Park” first intimated that something similar might be true of rats, animal research on addiction has convincingly demonstrated that…cocaine-addicted rats will…forego cocaine and choose alternative goods, such as saccharin or same-sex snuggling, if available. In short, the evidence is strong that drug use in addiction is not involuntary: addicts are responsive to incentives and so have choice and a degree of control over their consumption in a great many circumstances.

Experimental studies show that, when offered a choice between taking drugs or receiving money then and there in the laboratory setting, addicts will frequently choose money over drugs. Finally, since Bruce Alexander’s seminal experiment “Rat Park” first intimated that something similar might be true of rats, animal research on addiction has convincingly demonstrated that…cocaine-addicted rats will…forego cocaine and choose alternative goods, such as saccharin or same-sex snuggling, if available. In short, the evidence is strong that drug use in addiction is not involuntary: addicts are responsive to incentives and so have choice and a degree of control over their consumption in a great many circumstances. The second reason to maintain a choice model of addiction is that the process of overcoming addiction through a sense of agency, empowerment, and personal growth and self-understanding — a process that Lewis describes in The Biology of Desire with great care and acuity — itself presupposes that addicts have choice and a degree of control. Agency needs to exist to be mobilized: you can only decide to quit and do what it takes to stop using and change how you live and the kind of person you are if you have some choice and control over your use and your identity.

The second reason to maintain a choice model of addiction is that the process of overcoming addiction through a sense of agency, empowerment, and personal growth and self-understanding — a process that Lewis describes in The Biology of Desire with great care and acuity — itself presupposes that addicts have choice and a degree of control. Agency needs to exist to be mobilized: you can only decide to quit and do what it takes to stop using and change how you live and the kind of person you are if you have some choice and control over your use and your identity. sensory curiosity – expanded experiential horizon; and, finally, (7) euphoria and hedonia – in other words, pleasure. Drugs make us feel good, provide relief from suffering, and help us do various things we want to do better. [It] is difficult to see what could possibly be wrong with using drugs in and of itself. Suppose now we ask a further direct question: When use escalates to the point of addiction, who is to be held responsible for the ensuing negative consequences? According to the moral model, it is addicts themselves, who are not only responsible but [blameworthy], as they are considered to be fundamentally people of bad character with antisocial values… As an advocate of a choice model of addiction, I do not of course deny that some responsibility — but, crucially, responsibility as distinct from blame — lies with addicts themselves… The point I wish to emphasise however is that, in placing blame squarely on addicts or their disease, both models are united in enabling us to keep the focus of our attention away from ourselves and our society, avoiding the question of whether we, as a society, also collectively bear some responsibility for drug use and addiction and their consequent harms.

sensory curiosity – expanded experiential horizon; and, finally, (7) euphoria and hedonia – in other words, pleasure. Drugs make us feel good, provide relief from suffering, and help us do various things we want to do better. [It] is difficult to see what could possibly be wrong with using drugs in and of itself. Suppose now we ask a further direct question: When use escalates to the point of addiction, who is to be held responsible for the ensuing negative consequences? According to the moral model, it is addicts themselves, who are not only responsible but [blameworthy], as they are considered to be fundamentally people of bad character with antisocial values… As an advocate of a choice model of addiction, I do not of course deny that some responsibility — but, crucially, responsibility as distinct from blame — lies with addicts themselves… The point I wish to emphasise however is that, in placing blame squarely on addicts or their disease, both models are united in enabling us to keep the focus of our attention away from ourselves and our society, avoiding the question of whether we, as a society, also collectively bear some responsibility for drug use and addiction and their consequent harms. struggle with mental health problems, and are members of minority ethnic groups or other groups subjected to prejudice and discrimination. They may experience extreme psychological distress alongside a host of mental health problems apart from their addiction, feel a lack of psychosocial integration, and are at a socioeconomic disadvantage such that they have severely limited

struggle with mental health problems, and are members of minority ethnic groups or other groups subjected to prejudice and discrimination. They may experience extreme psychological distress alongside a host of mental health problems apart from their addiction, feel a lack of psychosocial integration, and are at a socioeconomic disadvantage such that they have severely limited  opportunities. These circumstances are central to understanding addiction in many contexts. Put crudely, the reason is simply that drugs offer a way of coping with stress, pain, and some of the worst of life’s miseries, when there is little possibility for genuine hope or improvement… In such circumstances, whatever harms accrue from using drugs must be weighed against whatever harms accrue from not using them. For this reason, the explanation of addiction and its associated negative consequences must lie in no small part with the psycho-socio-economic circumstances that cause such suffering and limit opportunities. And the existence of these circumstances is a feature of our society for which we must all collectively take some responsibility.

opportunities. These circumstances are central to understanding addiction in many contexts. Put crudely, the reason is simply that drugs offer a way of coping with stress, pain, and some of the worst of life’s miseries, when there is little possibility for genuine hope or improvement… In such circumstances, whatever harms accrue from using drugs must be weighed against whatever harms accrue from not using them. For this reason, the explanation of addiction and its associated negative consequences must lie in no small part with the psycho-socio-economic circumstances that cause such suffering and limit opportunities. And the existence of these circumstances is a feature of our society for which we must all collectively take some responsibility.

and use. You should just give up and settle for less, because this isn’t gonna get any better. Besides, nobody will know…or care.

and use. You should just give up and settle for less, because this isn’t gonna get any better. Besides, nobody will know…or care. One of the Trumpocalypse’s unintended contributions to the rational world was the reminder that not everything we hear on the news is real. Neither is everything we hear in our heads — especially the automatic negative thoughts blaring from our own fake news channel.

One of the Trumpocalypse’s unintended contributions to the rational world was the reminder that not everything we hear on the news is real. Neither is everything we hear in our heads — especially the automatic negative thoughts blaring from our own fake news channel. Fake news triggers urges, and vice versa. The satellite feed for the lead story originated long ago and far away — for some of us the stories started in early childhood. The stories can be as incessant as muzak playing over and over in your head. We have to change the channel to stay ahead of it…to stay in front of the fuck-its. Because when do the fuck-its happen? When terrorists demand action, now — no time to stop and think — or else.

Fake news triggers urges, and vice versa. The satellite feed for the lead story originated long ago and far away — for some of us the stories started in early childhood. The stories can be as incessant as muzak playing over and over in your head. We have to change the channel to stay ahead of it…to stay in front of the fuck-its. Because when do the fuck-its happen? When terrorists demand action, now — no time to stop and think — or else. Fake news is now not only a meme but an apt tag for the harmful diatribes that go off in our heads and often drive our behavior. But if we can recognize them, we can label them, and if we can label them, we can stop listening. If we can slow down enough to classify the news as real or fake, then, if it’s fake, we can turn down the volume — all the way down.

Fake news is now not only a meme but an apt tag for the harmful diatribes that go off in our heads and often drive our behavior. But if we can recognize them, we can label them, and if we can label them, we can stop listening. If we can slow down enough to classify the news as real or fake, then, if it’s fake, we can turn down the volume — all the way down.

I think the main reason is that our thinking and feeling, our personalities, and consciousness itself are so immediate, so personal, that we can’t entertain the idea that they emerge from electrochemical pulses among a bunch of cells. Our experience is so intricate, nuanced, and private — it’s difficult to imagine that it comes from a remarkable bodily organ. This paradox has been a real problem for philosophers ever since the time of the Greeks. It was made famous by Descartes, who said there must be some part of us that does not come from our bodies: this was termed “mind-body dualism.”

I think the main reason is that our thinking and feeling, our personalities, and consciousness itself are so immediate, so personal, that we can’t entertain the idea that they emerge from electrochemical pulses among a bunch of cells. Our experience is so intricate, nuanced, and private — it’s difficult to imagine that it comes from a remarkable bodily organ. This paradox has been a real problem for philosophers ever since the time of the Greeks. It was made famous by Descartes, who said there must be some part of us that does not come from our bodies: this was termed “mind-body dualism.” dark things we’ve thought and done. The dishonesty that often comes with addiction (the lying, stealing, etc) feels like an incontrovertible personal failure, unforgiveable (at some level) because…well because shouldn’t I be a better person?

dark things we’ve thought and done. The dishonesty that often comes with addiction (the lying, stealing, etc) feels like an incontrovertible personal failure, unforgiveable (at some level) because…well because shouldn’t I be a better person? according to the codes built into it over millions of years of evolution, most critically: attempt to minimize suffering and maximize relief. Stave off deprivation. And it puts those requirements above other goals, like obeying social conventions. This brain of yours has been adjusting to whatever has happened to you every single day since (and before) your birth. And some of what’s happened to you has no doubt been frightening, uncontrollable, and perhaps deeply traumatic.

according to the codes built into it over millions of years of evolution, most critically: attempt to minimize suffering and maximize relief. Stave off deprivation. And it puts those requirements above other goals, like obeying social conventions. This brain of yours has been adjusting to whatever has happened to you every single day since (and before) your birth. And some of what’s happened to you has no doubt been frightening, uncontrollable, and perhaps deeply traumatic. rather not do aren’t simple choices between right and wrong. They arise from a sequence of developmental adaptations in an organ that does its best to keep us going in a hugely challenging world.

rather not do aren’t simple choices between right and wrong. They arise from a sequence of developmental adaptations in an organ that does its best to keep us going in a hugely challenging world.

flavours? The chocolate sprinkles?

flavours? The chocolate sprinkles?