I recently came across a paper in Addiction Biology called “Recent updates on incubation of drug craving: a mini-review.” The studies summarized here show that drug craving increases progressively for weeks after we stop using. And by “we” I mean rats, mice, and humans, all experimental subjects in this review.

Since many of my readers are “in recovery” — and maybe I am too — this may not come as a big surprise. But rats? What’s the story here? And what does it tell us about how to help ourselves get through this difficult time?

Well, we’re all mammals and we share a lot of the same neural hardware — in particular the amygdala and the nucleus accumbens. I’ll remind you what those do in a minute, but for now let’s just call them the motivational engine of the brain. What I want to emphasize here is that, besides these similarities, humans have other problems that make rodent life look like easy street. We have this enormous cortex (linked to a hippocampus that fills it with zillions of explicit, linked memories), and so the cues that trigger craving often come from, and are magnified by, our own ruminations. That can be a real drag.

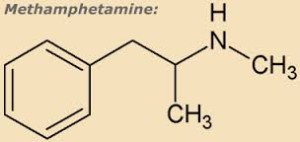

Most of the studies in this review involve rats. In a typical study, rats get themselves addicted to cocaine, meth, or heroin (with considerable help from humans), and then once they start taking it reliably, on their own, their supply is cut off. After the  withdrawal period is over, they are given cues that are associated with the drug they were on. These are called “conditioned stimuli” in Pavlovian conditioning. And then the experimenters measure how much they crave the drug (based on how much they take it, or how much they hang out in the place where it gets delivered) in the days and weeks that follow. The craving goes up, not down, as time goes on. And then finally it peaks and diminishes several weeks later.

withdrawal period is over, they are given cues that are associated with the drug they were on. These are called “conditioned stimuli” in Pavlovian conditioning. And then the experimenters measure how much they crave the drug (based on how much they take it, or how much they hang out in the place where it gets delivered) in the days and weeks that follow. The craving goes up, not down, as time goes on. And then finally it peaks and diminishes several weeks later.

The first thing to note is that the craving is always “cue induced.” It is literally triggered by a sight or sound — a green light or a buzzer — that previously meant “Come and get it!”

The second thing to note is that the incubation period, the period of increasing craving, is longer than we might like, but it’s not forever. Typically 10 days to a few weeks for rats. For humans, undoubtedly longer (in one study, it peaked at 60 days abstinence for alcoholics; in another, it peaked at 3 months for meth users).

It’s very important to realize that craving in the absence of cues decreases much more quickly, often beginning almost immediately after quitting.

What’s going on in the rat’s brain that makes it vulnerable to cue-induced craving? The amygdala is the main culprit, and the nucleus accumbens (ventral striatum) is its partner in crime. The amygdala registers rapid emotional significance. If something  is emotionally meaningful, whether the emotion is fear, anger, desire, or whatever, the amygdala will increase its firing. This is where the cue starts the process of emotional arousal and readiness. Then the nucleus accumbens takes over (stoked as it is by a tide of dopamine, thanks to the amgydala’s output). As you know from my writing, the nucleus accumbens is the part of the brain that produces an urge go after a goal: it narrows attention to the goal, gives you that feeling of “I really want it”, and then activates behaviours…like prancing to the part of the cage where the coke gets dispensed, if you’re a rat, or picking up the phone and calling your dealer, if you’re a human.

is emotionally meaningful, whether the emotion is fear, anger, desire, or whatever, the amygdala will increase its firing. This is where the cue starts the process of emotional arousal and readiness. Then the nucleus accumbens takes over (stoked as it is by a tide of dopamine, thanks to the amgydala’s output). As you know from my writing, the nucleus accumbens is the part of the brain that produces an urge go after a goal: it narrows attention to the goal, gives you that feeling of “I really want it”, and then activates behaviours…like prancing to the part of the cage where the coke gets dispensed, if you’re a rat, or picking up the phone and calling your dealer, if you’re a human.

If you’re a rodent, that’s all it takes. Craving is the emotional response to something you have learned. You’ve learned that something felt really nice, and it might be available, and because your brain is efficient and determined, you’re going to go after it. I should mention that rats on a high sugar diet show very much the same response once they’re cut off. So we’re not just talking about drugs.

If you’re a rodent, that’s all it takes. Craving is the emotional response to something you have learned. You’ve learned that something felt really nice, and it might be available, and because your brain is efficient and determined, you’re going to go after it. I should mention that rats on a high sugar diet show very much the same response once they’re cut off. So we’re not just talking about drugs.

But what if you’re a human? — and I assume you are if you’ve read this far. Then you’ve got a whole other set of problems. The initial cue can be the hands on the clock, telling you it’s about that time. It can be a mental image, a rumbling in your gut, the ragged touch of rising depression. It can be a baggie, an email, a neon sign, a dream. So far, you’re just a very intelligent rat. Your amygdala just sent a surge of dopamine to your nucleus accumbens — you’re alert, wanting, wishing… But you’re also thinking, and that’s where things get much worse.

You’re thinking that the day feels so empty without it. What am I going to do with my time? Thinking that there’s really nothing that can fill that gap. Thinking maybe that you deserve it, or you deserve how shitty you’re going to feel tomorrow, or both. One thought leads to another leads to

You’re thinking that the day feels so empty without it. What am I going to do with my time? Thinking that there’s really nothing that can fill that gap. Thinking maybe that you deserve it, or you deserve how shitty you’re going to feel tomorrow, or both. One thought leads to another leads to  another, and these thoughts fill your head. The amygdala and accumbens both connect to many many parts of the cortex, and they literally unleash these thoughts, which then trigger other related thoughts through direct synaptic connections. That’s rumination.

another, and these thoughts fill your head. The amygdala and accumbens both connect to many many parts of the cortex, and they literally unleash these thoughts, which then trigger other related thoughts through direct synaptic connections. That’s rumination.

The problem is that the habit you’ve developed isn’t just a learning and feeling habit — it’s a thinking habit. And until you start to become accustomed to living without that thing, those habits have little to replace them.

So, it would be ideal to avoid cues, but that’s just not entirely possible, since they can come from anywhere (including your own brain). In which case, you have to work on your thinking habits until the cue-trigger starts to lose its force (this can take weeks or months for humans) and until thought patterns readjust substantially.

But how do you work on those ingrained habits of thought? There are many ways. Two come to mind immediately:

- Shift your thinking as soon as you start to ruminate. Don’t even wait ten seconds. You can turn off cascades of thinking far more easily before they build momentum.

- Fill your days with other attractive, compelling activities. Provide your day with contour: a beginning, middle and end, so that the rumination habits don’t have so much traction.

But there’s one more highly valued strategy, and in this you’re no different from a rat. Get connected to others when you quit. Cue-induced craving is greatly reduced by “environmental enrichment” for rats and for humans. (Remember Rat Park?) From the journal:

In 2012, Thiel et al. (2012) demonstrated that environmental enrichment reduces incubation of cocaine craving. They first trained rats to self-administer cocaine for 15 days (3 hours/day) and then either housed rats individually or exposed them to an enriched environment (group housing, toys and running wheels, etc.) during the withdrawal period. They found that environmental enrichment reduced cue-induced cocaine seeking on both withdrawal days 1 and 21.

And one more thing: Be brave.