…by Bill Abbott, M.D….

Bill has been a long-standing member of this blog community and he has contributed his leadership and knowledge to the SMART Recovery movement. Thanks, Bill, for taking the time to share your thoughts here.

……….

I’ve recently completed two books. The first is Marc Lewis’s recent one and it is a winner. In this book Marc describes a “model” to explain addiction that is counter to the prevailing “disease model” and he does so in a very credible and lucid way that is based on neuroscience integrated with personal experiences of people he interviewed. A very effective approach indeed.

The second book, republished recently, is entitled Love and Addiction by Stanton Peele, which was first published in 1975 – 40 years ago. In this book (and other books of about the same vintage, such as Diseasing of America) Peele described the problem of addiction in very similar ways – obviously without the neuroscience available today — and showed the similarities between addiction and some forms of love, as Marc does also.

The second book, republished recently, is entitled Love and Addiction by Stanton Peele, which was first published in 1975 – 40 years ago. In this book (and other books of about the same vintage, such as Diseasing of America) Peele described the problem of addiction in very similar ways – obviously without the neuroscience available today — and showed the similarities between addiction and some forms of love, as Marc does also.

This has left me both frustrated and somewhat sad – that is, so much was clear forty years ago and yet we seem to have learned so little, and I can only come to conclude the following:

- The current way we approach the problem of addiction in the United States is abysmal; it isn’t working because it is wrong.

- We have failed to learn from our mistakes.

- Much of what we really need to know to understand addiction has been known for a long time, but we haven’t paid attention.

- We know enough about the problem to effectively deal with it.

- And finally, the disease model is not only wrong; it is harmful.

Marc suggests that the disease model is harmful to a certain extent, but my purpose here is to expand on that idea. I feel justified perhaps because I am a medical doctor — and in long term recovery from alcohol misuse.

As a disclaimer, what I describe pertains to the United States, where I live… but probably to some extent to other western countries as well.

The harm stems from two sources:

The harm stems from two sources:

The first is a practical issue. If addiction is a disease, doctors will be expected to “treat” it. That may not be too bad in theory, but unfortunately the medical profession (in the United States at least) is ill-prepared by virtue of knowledge, training, and — most problematic — insufficient time.

What about psychiatrists, you say? They are doctors. This is true (although many seem to forget clinical medicine)… but because they are doctors they treat patients by managing their patient’s diseases by prescribing medication, hoping for cure.

The underscored words lead to the second and greater problem with the brain disease model; and that is that it shifts the focus away from people with a problem to an outside entity, thereby mitigating personal responsibility. This position in essence means looking for an outside solution for an inside problem…that only an inside solution can help.

Let me expand on that a little.

Marc brings up two very important concepts in his book: what he calls “now appeal” (officially delay discounting) and ego fatigue or depletion (the depletion of cognitive resources for applying self-control). A related idea is the concept of locus of control.

This concept has been around for a number of years and has been described a number of ways. In general terms what it refers to is whether an individual believes in or relies on self-management or tends to look to  outside resources for problem solving. This is not a fixed or constant trait but rather a tendency that varies with the problems and stresses people face. It often tends to be more on the external side in those encountering hard times – not uncommon in the addicted person. Some incorrectly call it low self-esteem.

outside resources for problem solving. This is not a fixed or constant trait but rather a tendency that varies with the problems and stresses people face. It often tends to be more on the external side in those encountering hard times – not uncommon in the addicted person. Some incorrectly call it low self-esteem.

So if addiction is a formerly useful coping strategy, now gone amiss, then one needs to look for other coping strategies that work better and be motivated to put them to use. And these work better if they are self-empowered. They don’t work if you rely on someone or something else. They just can’t.

The neuroscience points to the same conclusion; it is the “desire” that Marc is talking about that makes recovery work.

What is needed is a shift toward an internal locus of control. Something which the disease model tends to undermine because it fosters dependence on another power.

Surely you can and ought to seek help, advice, support, or what have you, if that can help. But ultimately you have to do it—for yourself

This is why the disease model is so insidious and counterproductive to successful recovery in many people. Although your doctor will encourage your participation, basically he is telling you what to do. This is prescription — be it medication or behavior. “You must stop drinking or you will die,“ my doctor said to me. I went home and poured a drink to think about that.

The evidence supporting the self-management approach is all over the place.

Consider so-called natural or spontaneous recovery — statistics show that as many as 80% of those who meet criteria for substance use disorder in the DSM-5 recover with no intervention or support whatsoever.

This is the epitome of self-management and empowerment.

For those who do need some help, self-management can be learned or better relearned in any number of ways… but I am skeptical that it will ever be learned in a doctor’s office, where you wait next to people with medical illnesses like hypertension and hemorrhoids.

A disease like cancer needs the doctor to manage it; addiction does not.

A disease like cancer needs the doctor to manage it; addiction does not.

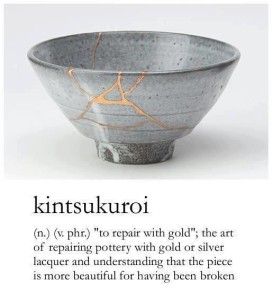

What those of us who solved the problem of addiction share is self-empowerment and then learning the skills to manage life’s many stresses in a different and ultimately less destructive manner.

The whole disease model concept is based on some really bad science and that in itself is harmful. But the fallout is potentially more damaging.

The whole disease model concept is based on some really bad science and that in itself is harmful. But the fallout is potentially more damaging.

I only hope people start paying attention, because the problem is getting worse and we gotta do better. The people who suffer deserve that much, and if we help them to see what they can do for themselves, they may in fact do it — and feel good about the fact that they did.