…by Matt Robert…

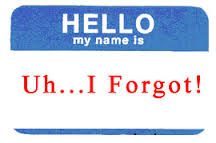

When I was finally ready to stop, I began the ignominious journey of failing at rehab after rehab. My resolve to stay clean was firm, but I often struggled with aspects of treatment. One of the most baffling things to me was how people were told to refer to themselves in meetings. “Joe– alcoholic/addict.” It never sat right with me. But virtually no one in the programs would sit down and explain it to me. Why should someone refer to themselves  as the very thing they were trying not to be? I had to go to 3 or 4 meetings a day in residential treatment, and I noticed that this repeated, retrograde self-disclosure had unintended effects. When people were called to the phone, they often stumbled and said, “Hello, this is Jim– alcoholic.”

as the very thing they were trying not to be? I had to go to 3 or 4 meetings a day in residential treatment, and I noticed that this repeated, retrograde self-disclosure had unintended effects. When people were called to the phone, they often stumbled and said, “Hello, this is Jim– alcoholic.”

Early on I stopped adhering to this meeting routine. It made me feel worse, not better. I had no illusions about my problem and did not harbor the fantasy that I would be able to use again in safety. But the self-naming routine made me feel resistance, not acceptance. Sometimes, when it was my turn in the in-house meetings, I made something up:

“Hi, I’m Matt. Chemical Recycling Dump.”

“Hi, I’m Matt. Chemical Recycling Dump.”

“Matt, Emotional Disaster Area.”

“Matt, Seething Cauldron of Broken Dreams and Missed Opportunites.”

It had never occurred to me that there were so many sarcastic, unsympathetic ways to refer to addicts. I started sifting through the alphabet for the day’s meeting moniker, (Altruistic, Atheist Addictoholic, Benevolent Bipolar Boozebag, etc….). I had to keep a sense of humor in all this. Otherwise, I was lost.

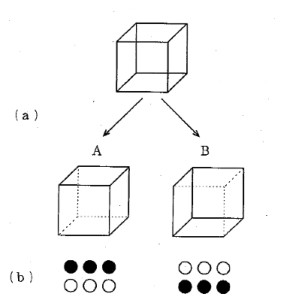

Finally, I began to piece together the reasoning behind the practice: by calling myself an addict it meant I was gradually accepting it, “faking it till you make it,” at least until my sobriety started to stick. This practice was supposed to keep my awareness on the problem— to keep it fresh, keep it green, keep it up front— to be a part of the community, and the fellowship, and not alone.

I could see the benefit of repeating the label as a pseudo-reality check when someone is in denial that there is a problem, when they’re still in the subacute phase of early recovery. But after we move deeper into recovery, I couldn’t see the point anymore. It was counterintuitive and, for me, counterproductive. By self-identifying, I was reinforcing my connection to a negative behavior that I was trying to replace with something positive. I realize this doesn’t happen for everyone who attends 12-Step meetings. I still attend AA/NA meetings, but because of the personalities, not the principles. It’s the people who I identify with. My principles are fine, otherwise my sobriety wouldn’t be. The most important thing about meetings is to find ones that we like— where we can relate to someone’s story, where we feel better when we leave than when we walked in. Meetings that make us want to stay clean.

anymore. It was counterintuitive and, for me, counterproductive. By self-identifying, I was reinforcing my connection to a negative behavior that I was trying to replace with something positive. I realize this doesn’t happen for everyone who attends 12-Step meetings. I still attend AA/NA meetings, but because of the personalities, not the principles. It’s the people who I identify with. My principles are fine, otherwise my sobriety wouldn’t be. The most important thing about meetings is to find ones that we like— where we can relate to someone’s story, where we feel better when we leave than when we walked in. Meetings that make us want to stay clean.

I facilitate a group at an inpatient program for homeless women waiting to be placed in sober living situations. I’m there to tell them about SMART Recovery as another option, but my goal is not to push any particular agenda or approach. It’s to get them to go to meetings. Any meetings. We have an open discussion around that, which starts to resemble a SMART meeting. When I first started going , we collectively agreed on a way for everyone to introduce themselves. I would explain the skewed logic of labeling, and suggest that during introductions you could say your name, something about who you are or are working toward (not what you are trying not to be), and an adjective about how you are feeling that night. A similar approach is portrayed in the documentary The Anonymous People and is powerful and compelling: “My name’s Sue…and I’m a person in longterm recovery (…or early recovery…or trying to stay clean).” “I’m Jill, a mother of 4 who likes rock climbing. Tonight, I’m feeling hopeful.”

By the time we get around the room, everyone knows a little more about each other and where they are at emotionally that night. It often makes for a deeper, more meaningful discussion. People learn things about each other.

Sometimes there are longtime AA members in the meeting who are resistant to this different way of self-introduction, just as I was resistant to the traditional AA self-introduction practice. I try to encourage them to remain open-minded (something also stressed in the Big Book). Try everything that seems to help, and accept suggestions. Because we never know where or when that opportunity, that moment of clarity, that motivational window will appear, and we don’t want to miss it.

Sometimes there are longtime AA members in the meeting who are resistant to this different way of self-introduction, just as I was resistant to the traditional AA self-introduction practice. I try to encourage them to remain open-minded (something also stressed in the Big Book). Try everything that seems to help, and accept suggestions. Because we never know where or when that opportunity, that moment of clarity, that motivational window will appear, and we don’t want to miss it.