…by Peter Sheath (lightly edited by Marc)…

Here is a more detailed account of the community-wide treatment approach being implemented in Birmingham. Thanks very much to Peter for stepping up to the plate. Note that this post is a response to the questions and concerns raised by blog members following my last post.

——————

I’m pretty much overwhelmed by your positive messages and support. It’s taken some time to get to this point. Now we are about to take the quantum leap of helping people begin to deal with addiction problems within their community — as a community. The program has much in common with policies implemented in Portugal, where there have been dramatic reductions in almost everything negative associated with drugs. If it works, and many of us firmly believe it will, it will be a real game changer for the way we approach health care in general. It will help move us away from the “deficits approach” — needing an “expert” for just about every problem we encounter within our societies — to a more co-productive community-based “expert by experience” model, whereby people can take responsibility for resolving their own problems.

Jasmine makes some great points, and we have thought long and hard about almost every one of them. The only one I don’t get is her query, “how the heck could this not create a sense of stigma, othering, and sense of hierarchy?” Much of the model is already happening in a very informal way all across Birmingham.  The city is probably the most diverse city in the UK, with lots of communities where English isn’t the first language — communities that just wouldn’t dream of looking for outside help. Part of my role has been to find out what goes on in these communities, how they deal with addiction, and if there’s anything we (ROR) can do to help. Most of the time all I’ve found are very dedicated people doing it for themselves, having developed some astonishing networks involving community elders and local businesses. Far from stigmatizing addiction, these networks have served to normalize it and, in many ways, make it the responsibility of the community.

The city is probably the most diverse city in the UK, with lots of communities where English isn’t the first language — communities that just wouldn’t dream of looking for outside help. Part of my role has been to find out what goes on in these communities, how they deal with addiction, and if there’s anything we (ROR) can do to help. Most of the time all I’ve found are very dedicated people doing it for themselves, having developed some astonishing networks involving community elders and local businesses. Far from stigmatizing addiction, these networks have served to normalize it and, in many ways, make it the responsibility of the community.

Note that the start date of our project is March 3, and the leaflet that Jasmine is referring to is intended for interested parties, professionals and commissioners. Once we launch, we intend to consult with service users to develop a pamphlet that’s both user friendly and accurate.

Most of the people we will be working with are already engaged with community resources on a daily basis. Nearly 5000 are in receipt of opiate substitute prescribed medications, which they pick  up most days of the week from a community pharmacy, and around another 1000 are accessing the various needle exchanges delivered by community venues. Most people with alcohol problems presently go to either their general practitioner or a community pharmacist as a first point of contact. But most of those professionals have little or no support, supervision and/or training, so they simply refer them on to the alcohol team. That usually causes further delay in getting the necessary help — a problem that could have been resolved at first point of contact.

up most days of the week from a community pharmacy, and around another 1000 are accessing the various needle exchanges delivered by community venues. Most people with alcohol problems presently go to either their general practitioner or a community pharmacist as a first point of contact. But most of those professionals have little or no support, supervision and/or training, so they simply refer them on to the alcohol team. That usually causes further delay in getting the necessary help — a problem that could have been resolved at first point of contact.

We have gone to great lengths to ensure that professional help, when needed, is easily accessible and readily available. Clinicians, keyworkers, and structured group activities are never more than a short bus ride away and available within community centres, libraries, etc. The ROR outlets, pharmacies, retail premises, eventually taxi drivers, and many other participants will know exactly where an d at what time help is available. All sorts of on-line/telehealth support will be available as backup. We are hoping that, as the community develops and community champions come forward, professionals can begin to focus on people with complex issues and those who have become dependent on the treatment system for years. Anyway, as you can no doubt imagine, I have work to do, please watch this space for further updates.

d at what time help is available. All sorts of on-line/telehealth support will be available as backup. We are hoping that, as the community develops and community champions come forward, professionals can begin to focus on people with complex issues and those who have become dependent on the treatment system for years. Anyway, as you can no doubt imagine, I have work to do, please watch this space for further updates.

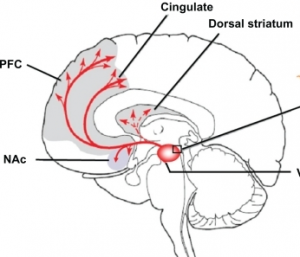

Thank you very much, Richard, for your support. I agree with everything you’ve said, and your words resonate with my experience, both as a person who couldn’t deal with life without substances and as a person who has dedicated his life to try to make things better. I believe the answer lies just where it always has, in the community. We, the treatment industry, have in many ways created a monster: we have persuaded people that they are sick and they need professional help to get better. Just as the great Bruce Alexander, Carl Hart and Marc have been saying, addiction is what happens when people try to soothe away things like dislocation, marginalization, poverty, and dissa tisfaction. Yet these come about because of the systems or communities people come from. If we create an environment where communities can begin to heal themselves and their members can take responsibility for

tisfaction. Yet these come about because of the systems or communities people come from. If we create an environment where communities can begin to heal themselves and their members can take responsibility for each other, then maybe change can happen. Up until now, focusing on individuals, isolating them, and treating them as sick has not taken us where we need to go.

each other, then maybe change can happen. Up until now, focusing on individuals, isolating them, and treating them as sick has not taken us where we need to go.

xclusion from evaluations of how they’re doing, what they’re doing, and when they’ve had enough. At the outset they are told, “We’ll have to break you down so we can build you back up again”—a phrase commonly heard in institutional settings, according to Matt Robert, a friend, former addict, and group facilitator in both institutional and community-based programs. It’s not that such policies are borne of ill intent. It’s just that they’re wrong-headed. Disease model advocates like

xclusion from evaluations of how they’re doing, what they’re doing, and when they’ve had enough. At the outset they are told, “We’ll have to break you down so we can build you back up again”—a phrase commonly heard in institutional settings, according to Matt Robert, a friend, former addict, and group facilitator in both institutional and community-based programs. It’s not that such policies are borne of ill intent. It’s just that they’re wrong-headed. Disease model advocates like