Hi you people! I haven’t forgotten about you. In fact I really miss you. This blog community has been like a second family to me, and I’ve gotten a lot of warmth and a lot of learning from communicating with you.

As I mentioned last summer, I’ve moved to L.A. with my family — temporarily. And I’ve spent the last two months feverishly trying to finish my new book: The Biology of Desire: Why Addiction is Not a Disease. That’s why I haven’t been posting.

I have to get a full draft to my publishers by tomorrow, then I’ll be off traveling again (this time to South America!) for two weeks. Then I think I’ll be able to start regular posting again.

For now, I’ll copy the first few paragraphs of the book. It’s still only a draft, and the argument will be old news to those of you who have followed this blog. But it’s the best summary I can give you of what I’ve been thinking and writing about.

“Public attention has been riveted by the harm addicts cause themselves and those around them. More in the last few years than ever before. And the way we view addiction is changing, molting, and perhaps advancing at the same time. We’ve begun to separate our ideas about addiction from assumptions about moral failings. We’re less likely to dismiss addicts as simply indulgent, spineless, lacking in willpower. It becomes harder to relegate addiction to the down-and-outers, the gaunt-faced youths who shuffle toward our cars at traffic lights. We see that addiction can spring up in anyone’s backyard. It attacks our politicians, our entertainers, our relatives, and often ourselves. It’s become ubiquitous, expectable, like air pollution and cancer.

To explain addiction seems more important than ever before. And the first explanation that occurs to most people is that addiction is a disease. What else but a disease could strike anyone at any time, robbing them of their wellbeing, their self-control, and even their lives? There is indisputable evidence for physiological changes with addiction. Research over the last 20 years reveals distinct alterations in brain structure and function that parallel substance abuse. This seems to clinch the definition of addiction as a disease — a physical disease. And it gives us hope, or at least forebearance; because the notion is sensible, comforting in its own way, and part of our shared reality. If addiction is a disease, then it should have a cause, a time course, and possibly a cure, or at least agreed-on methods of treatment. Which means we can hand it over to the professionals and follow their directions.

But is addiction really a disease?

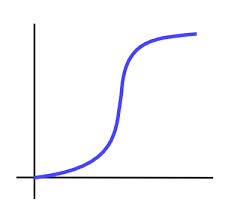

This book makes the case that addiction results from the motivated repetition of certain thoughts and behaviors until they become self-perpetuating habits. Thus, addiction develops, and it can develop quickly, through a process I call accelerated learning. A close look at the brain tells us why this occurs: because the neural circuitry of desire governs many other brain functions, so that highly attractive goals will be pursued repeatedly, and that repetition (not drugs, booze, or gambling) will change the brain’s wiring. As with other entrenched habits, this developmental process is underpinned by a neurochemical feedback loop that’s present in all normal brains but now spirals more quickly than usual because of the allure (and repeated pursuit) of particular goals. There’s mounting evidence that addiction arises from the same neural hardware that binds children to their parents and lovers to each other. And it builds on the same cognitive mechanisms that permit humans to seek goals selectively and to pursue symbols — goals that stand for something. Addiction is unquestionably destructive, yet it is also uncannily normal: an inevitable feature of the basic human design. That’s what makes it so difficult to grasp — societally, philosophically, scientifically, and clinically.

I believe that the disease idea is wrong, and that its wrongness is compounded by a biased view of the neural data — and by scientists’ habit of ignoring the personal. It’s an idea that can be replaced, not by shunning the biology of addiction but by examining it more closely, and then connecting it back to lived experience. Medical researchers are correct that the brain changes with addiction. But the way it changes has to do with learning and development — not disease. Addiction can therefore be seen as a developmental cascade, often foreshadowed by difficulties in childhood, always accelerated by the narrowing of perspective with recurrent cycles of acquisition and loss. Like other developmental outcomes, addiction isn’t easy to reverse, because it’s based on the restructuring of the brain. Like other developmental outcomes, it arises from neural plasticity, but its net effect is a reduction of further plasticity, at least for awhile. Addiction is a habit, which, like other habits, gets a major boost from the suspension of self-control. Addiction is definitely bad news for the addict and all those within range. But the severe consequences of addiction don’t make it a disease, any more than the consequences of violence make violence a disease, or the consequences of racism make racism a disease, or the folly of loving thy neighbour’s wife make infidelity a disease. What they make it is a very bad habit.

Although this book uses scientific findings to build its case, it works through the testimony of ordinary people. I relate detailed biographical narratives of five very different people, each struggling with addiction, as the scaffolding on which brain science is introduced and interpreted.Through these stories, I show what it’s like and how it feels when addiction takes hold, while explaining the neural changes underlying it. There’s no doubt that these changes mark a difficult passage in personality development. But I conclude each chapter on a positive note, following my contributors through their addictions to their growth beyond it — a phase often termed “recovery.” And I provide the neuroscientific facts and concepts to help us understand how they get there. Most addicts end up quitting: uniquely and inventively, through effort and insight. Thus quitting is best seen as further development, not recovery from a disease.”

Sayonara! More soon….