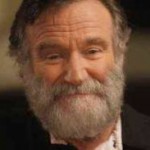

Now that the shock of it has passed, I’m left with a fog of sadness and anxiety, a sense of things being wrong in the world — more wrong than usual. Everyone loved Robin Williams. He gave so much of himself in his films and on-stage that we felt we knew him intimately. He was easy to connect with. He became part of our personal worlds.

Now that the shock of it has passed, I’m left with a fog of sadness and anxiety, a sense of things being wrong in the world — more wrong than usual. Everyone loved Robin Williams. He gave so much of himself in his films and on-stage that we felt we knew him intimately. He was easy to connect with. He became part of our personal worlds.

A few people have asked me what I think happened. Was his addiction to alcohol the problem, was it the inadequacy of his AA and other treatment choices, was it the shame he still carried during his dry periods, or his yearning to go back to booze and coke?

I think these are the wrong places to look for an explanation. In a somewhat bizarre interview with Decca Aitkenhead at The Guardian, published four years ago, Robin shifted the flow of dialogue directly to his personal problems.

After 20 years of abstinence, Robin started drinking again while shooting a film in Alaska in 2003. Here’s what he said about that moment in his life, quoted from the Guardian article:

After 20 years of abstinence, Robin started drinking again while shooting a film in Alaska in 2003. Here’s what he said about that moment in his life, quoted from the Guardian article:

“I was in a small town where it’s not the edge of the world, but you can see it from there, and then I thought: drinking. I just thought, hey, maybe drinking will help. Because I felt alone and afraid. It was that thing of working so much, and going fuck, maybe that will help. And it was the worst thing in the world.”

So why did he start drinking again?

[From the same article:] Some have suggested it was Reeve’s death that turned him back to drink. “No,” he says quietly, “it’s more selfish than that. It’s just literally being afraid. And you think, oh, this will ease the fear. And it doesn’t.” What was he afraid of? “Everything. It’s just a general all-round arggghhh. It’s fearfulness and anxiety.”

He continued drinking for about three years, then stopped. A residential rehab seemed to have helped, and he attended AA meetings about once a week since then.

He did not go back to drinking after that, as far as I know. But he must have been unable to deal with the anxiety that drove him to drink in the first place.

Those of us who’ve been through addiction know all about that fearfulness, that anxiety, that arggghhh. And the depression that is closely linked with it, and that reportedly engulfed Robin Williams in the last month of his life. Of those I’ve talked with, most have seen it up close, a jungle beast staring them eye to eye. I still feel it often. But I don’t use anymore, chiefly because that just makes things worse. Then the fear becomes concrete: this is what’s going to get me.

Otherwise, it’s just anxiety.

Just?!

We live in a dangerous world. The love and protection we got as children (whether we were smothered in it or had more occasional helpings) is gone. We realize that was a childhood gift. The world is a dangerous place. Everything is uncertain. We cannot control the threats of loneliness, loss of loved ones, the onset of disease or disability, the vice-like grip of sadness, and eventually old age (if you’re lucky) and death. We cannot even control our desperate deeds aimed at self-protection, harbingers of shame and self-loathing. At least not always.

We live in a time dominated by an existential view of reality. Few of us feel buoyed up by religion or hope of a pleasant afterlife. And yet we’re not very good at being here now. It’s not something we’re taught, and it doesn’t come naturally.

I think the fear, anxiety, the depression, the arggghh that became unbearable to Robin Williams is something we also know well. His death disturbs us so much, not only because we will miss him, not only because we feel for him, but because it reminds us of the brutality of that incessant uncertainty, that desolate isolation, which can turn into terror.

I think the fear, anxiety, the depression, the arggghh that became unbearable to Robin Williams is something we also know well. His death disturbs us so much, not only because we will miss him, not only because we feel for him, but because it reminds us of the brutality of that incessant uncertainty, that desolate isolation, which can turn into terror.

Of course we hear about the casualties. Philip Seymour Hoffman, and now Robin Williams. Yet most of us endure. We’ve learned something that Robin may have been too busy to learn. How to love ourselves a little. How to accept helplessness and keep going. How to absorb some degree of warmth and wonder from the universe, the same universe that refuses to grant us safety or permanence. Maybe battling our addictions  has made us stronger, more open, more accepting.

has made us stronger, more open, more accepting.

I’m sorry that wasn’t true for you, Robin.