I am finally finished the tapering period, finished getting off the oxycodone I was on pre- and post-surgery. It took about four weeks to go from 100 mg/day to zero. Nice and gradual, and I suffered nothing worse than a runny nose, some diarrhea, some insomnia, and a few twitches. Oh, and that sense of impending loss, depression, and despair. Did I mention that? The old circuits carrying that old message, because that’s what old circuits do.

So there I was, flickering into my “addict self,” as people like to call it, and thinking, I like this stuff and I’m not eager to stop…

I don’t remember who gave me this line — one of you, I’m sure: Quitting drugs is like going to the funeral of your best friend. Funny how it still feels like that. That’s what I anticipated. Not as intense as in the old days. But qualitatively pretty much the same.

I don’t remember who gave me this line — one of you, I’m sure: Quitting drugs is like going to the funeral of your best friend. Funny how it still feels like that. That’s what I anticipated. Not as intense as in the old days. But qualitatively pretty much the same.

What I wasn’t anticipating, what I’d forgotten about, was the relief I’m feeling now. An unexpected flush of freedom, breathing in lungfuls of fresh air. And feeling strong again. I feel centered, and focused, and strong. I feel like me again. It’s been awhile.

But…freedom from what? That is the big question, don’t you think? Freedom from the sense of impending loss, the sort of cowering that goes with ingesting something you imagine is enhancing your sense of okayness, knowing it’s not going to last, and putting  off the inevitable. Freedom from the compulsion, the greedy hording (mentally, at any rate) of the crumbs of wellbeing that I was still getting from these pills — even on a medically supervised, perfectly legal, moral, and even necessary detox regime. I was still getting the crumbs. And the freedom I feel now is from the anxiety — pure and simple: anxiety — about losing those crumbs.

off the inevitable. Freedom from the compulsion, the greedy hording (mentally, at any rate) of the crumbs of wellbeing that I was still getting from these pills — even on a medically supervised, perfectly legal, moral, and even necessary detox regime. I was still getting the crumbs. And the freedom I feel now is from the anxiety — pure and simple: anxiety — about losing those crumbs.

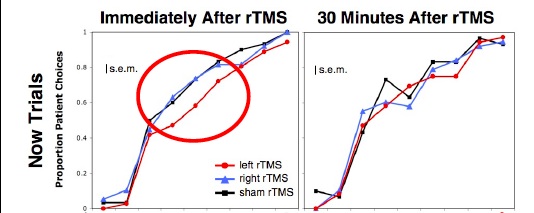

My last post addressed how it might be possible to make the future seem as good or better than the present, by adjusting the subjective value, the sense of value, of the immediate reward (drugs, booze, whatever) versus the long-term reward (that list of seeming  abstractions) and/or changing their timing. And then you guys asked, and I asked myself, how exactly do you do that? How do you do it for yourself (if you’re the addict) and how do you do it for someone else (if you’re the helper, sponsor, therapist, partner)? If we’re not in some artificial experimental setting, and it’s not just a matter of changing the numerals on a computer screen (e.g., from 10 to 45 euros in the “next week” column), how do you get the future to feel like it’s worth it?! Worth whatever you have to go through to “just say NO.”

abstractions) and/or changing their timing. And then you guys asked, and I asked myself, how exactly do you do that? How do you do it for yourself (if you’re the addict) and how do you do it for someone else (if you’re the helper, sponsor, therapist, partner)? If we’re not in some artificial experimental setting, and it’s not just a matter of changing the numerals on a computer screen (e.g., from 10 to 45 euros in the “next week” column), how do you get the future to feel like it’s worth it?! Worth whatever you have to go through to “just say NO.”

And here, ladies and gentlemen, is the answer. At least one answer.

Remind yourself or your addicted friend, lover, client or patient about this sense of relief! This feeling of being a whole person. Of being strong. Make it palpable. Get it back on the radar. Bring it to mind (hint: that’s the first half of the word “mindfulness”). This is what it feels like to finally be free of this shit! Remember? Do you get it? There is peace here.

Certainly there are twinges of wistfulness. Yes, some kind of magical sheen, winking on and off like an old neon sign, has gone missing. Craving still bunches up in your throat like a reflex, a need to swallow — or cough. But the place you land in, after these dust devils have passed…that place feels like home.

Certainly there are twinges of wistfulness. Yes, some kind of magical sheen, winking on and off like an old neon sign, has gone missing. Craving still bunches up in your throat like a reflex, a need to swallow — or cough. But the place you land in, after these dust devils have passed…that place feels like home.

Now, as to the details, how exactly to do that, I’m going to turn the floor over to someone in the treatment world. First up is my friend (through this blog) and long-time contributor (to this blog), Matt. And if anyone else would like to help us out here — anyone, but especially those of you in the treatment community — please do: get in touch about writing a guest post. Soon! I think we could all use some concrete ideas about manipulating awareness, about expanding awareness beyond the upcoming delivery of today’s lollipop, about shifting your focus…away from the siren call of the moment and back to the main voyage.