Hello all. I have to admit I’m becoming addicted (again!) — this time to addiction memoirs. I’ve read four in the last four months, all written by alcoholics:

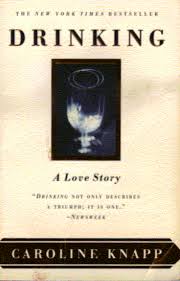

Drinking: A Love Story — Caroline Knapp.

Drunk Mom — Jowita Bydlowska.

Drunkard: A Hard-Drinking Life — Neil Steinberg.

The Couch of Willingness — Michael Pond & Maureen Palmer.

I’m still finishing the last two. I pick them up in my spare time, packed up on my Kindle for train rides and class breaks, or late at night when I’ve got time to myself. I really like them. I find them delightful, suspenseful, fascinating, epochal, and redemptive — redemption seems to be a big word in this genre.

But really, why do I like them so much? First, I’ve written one of my own. I know how the story goes from inside out. Second…okay, let me reconsider the list of adjectives I just used:

Delightful. Really? These are without exception intimate portrayals of people who are living horrific lives, cutting out hunks of flesh and soul without knowing how to stop, committing reprehensible acts and then choking on shame, guilt, and remorse. Why is that delightful?

Delightful. Really? These are without exception intimate portrayals of people who are living horrific lives, cutting out hunks of flesh and soul without knowing how to stop, committing reprehensible acts and then choking on shame, guilt, and remorse. Why is that delightful?

Suspenseful. I already know that they are going to keep drinking until they finally quit. And then they’re going to feel better. Where’s the suspense?

Fascinating. Ditto. The stories are remarkably similar, as though they are simply variations on a theme — sitcom formulas. I mean, right down to the details. They hide bottles all over the house. They get rid of empty bottles in the neighbours’ trash cans. They feel embarrassed going back to the same liquor store day after day. Then they go to another store. How is this fascinating?

Epochal. That’s a word used to describe Greek myths, classic tragedies, and so forth. These folks just get drunk a lot. How epochal is that?

Redemptive. Well, they do finally quit. (I’m still not sure about Neil Steinberg, having not gotten to the end. But I’d be surprised if he didn’t). But “redemption” seems like a pretty strong word for finally behaving in your own best interests rather than continuing to torment yourself and everyone around you.

Redemptive. Well, they do finally quit. (I’m still not sure about Neil Steinberg, having not gotten to the end. But I’d be surprised if he didn’t). But “redemption” seems like a pretty strong word for finally behaving in your own best interests rather than continuing to torment yourself and everyone around you.

So here are my best guesses at why those words came to mind:

Delightful. They are such human beings. Such an unpredictable, ever-changing mixture of strengths, weaknesses, suffering, defeat, pride, shame, and even humour. A fair bit of humour in the last three for sure. Because you have to laugh if you’re not going to cry. Or at least get some of each. These memoirs epitomize the complexities and virtues of humans facing and eventually overcoming astonishing challenges.

Suspenseful. When are you going to quit?! How are you going to do it?! You have tried so many times without success (often), I just can’t see how you’re going to pull it off, and I’m waiting for it with every page turned.

Suspenseful. When are you going to quit?! How are you going to do it?! You have tried so many times without success (often), I just can’t see how you’re going to pull it off, and I’m waiting for it with every page turned.

Fascinating. See “delightful”. But let me add that these are war stories, dramas, tragedies, and they describe unimaginable extremes of human desperation, depravity, creative problem-solving, and determination. So you really held an airplane bottle of vodka to one nostril, blocking the other, to inhale the fumes? Snorting booze? You poured your wine into baby bottles as camouflage? You really grabbed that bottle off the bar counter while the bartender turned her back? Unbelievable!

Epochal. But they really are epochs. Each and every one. Just as Shakespeare’s tragedies all followed the same formula, and yet each came across as unique, profound, one of a kind. Each one (at least each good one) carries us effortlessly along classic story lines constructed from the basic components of suffering, self-deception, and the inexplicable capacity — the heroic capacity — to come back from the jaws of defeat with your dukes up. Or to reshape your personality until that becomes possible. Addiction memoirs seem an obvious extension of classical drama into our modern age.

Epochal. But they really are epochs. Each and every one. Just as Shakespeare’s tragedies all followed the same formula, and yet each came across as unique, profound, one of a kind. Each one (at least each good one) carries us effortlessly along classic story lines constructed from the basic components of suffering, self-deception, and the inexplicable capacity — the heroic capacity — to come back from the jaws of defeat with your dukes up. Or to reshape your personality until that becomes possible. Addiction memoirs seem an obvious extension of classical drama into our modern age.

Redemptive. Well, what is redemption, anyway? I think it must presuppose the idea of sin, moral failing, finally overcome through some sort of penance that one endures voluntarily to become clean or whole once again. In his recent book, Lance Dodes mentions this assumption as built into the AA-inspired notion that you have to hit bottom before you’re ready to quit. But very often, you do. People fight like crazy to quit. And the most agonizing part of that fight is turning your back on the one thing that provided relief, support, and comfort. As Steinberg puts it, “attending the autopsy of someone you love.” That’s pretty damn courageous.

Addiction memoirs seem to tell the same tortuous story, often starting in the same place and ending in the same place, but with the incredible diversity, the unexpected creativity and novelty, the unanticipated twists and turns, partial victories, temporary failures, redoubts and stupidly courageous counterattacks, that derive from being one of an infinite variety of suffering humans. We are so different. And though addiction pulls us through roughly the same line-up of torture instruments, like those tours you can take through torture chambers in medieval castles — adults, 18 euros; kids, 8 euros — it does so in ways that never cease to surprise me, mesmerize me, and make me proud.