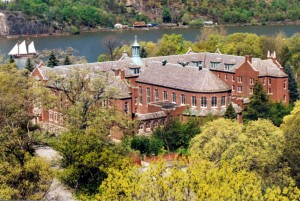

Just finished day 1 at the Mind and Life conference. What a beautiful building this is for a conference. The corridors seem to echo with the shuffling feet of Christian monks. But now, in our modern age, there are a lot of shaven-headed guys with orange robes walking around. It’s strange to see them in the washroom with everyone else, shaving, brushing their teeth. Very corporeal. But most people here are young scientist types, assistant profs or post-docs in psychology or neuroscience, but incredibly friendly and warm-hearted. And a few old guys, like me, except that they look like they’ve known each other for decades. It’s weird to meet a guy with a name like Saul Weinstein who turns out to be an expert on meditation.

Just finished day 1 at the Mind and Life conference. What a beautiful building this is for a conference. The corridors seem to echo with the shuffling feet of Christian monks. But now, in our modern age, there are a lot of shaven-headed guys with orange robes walking around. It’s strange to see them in the washroom with everyone else, shaving, brushing their teeth. Very corporeal. But most people here are young scientist types, assistant profs or post-docs in psychology or neuroscience, but incredibly friendly and warm-hearted. And a few old guys, like me, except that they look like they’ve known each other for decades. It’s weird to meet a guy with a name like Saul Weinstein who turns out to be an expert on meditation.

Today the talks were on heady Buddhist topics, loaded with Sanskrit and Tibetan words for different traditions. I had to struggle to focus. I’m still a bit jet-lagged and my mind is buzzing with worldly things. In fact today’s meditation session was a total write-off. Tomorrow’s talks will be on neuroscience. That should wake me up.

Today the talks were on heady Buddhist topics, loaded with Sanskrit and Tibetan words for different traditions. I had to struggle to focus. I’m still a bit jet-lagged and my mind is buzzing with worldly things. In fact today’s meditation session was a total write-off. Tomorrow’s talks will be on neuroscience. That should wake me up.

What’s most strange about this event is that I’m staying in a small room with another guy. Two beds side by side, and four tiny shelves for our stuff. I haven’t shared a room with a stranger since boarding school. He’s a prof in religious studies at a university in Pennsylvania. A nice guy, actually. Still, he’s very close.

Anyway, not much more to say for now, so what I’ll do is post the second half of an article I just wrote for the Mind & Life newsletter.

To prepare for the meeting [with the Dalai Lama], I’ve been trying to think like a Buddhist for the last few months. And what strikes me most is that the Buddhist perspective on personal suffering, based as it is on desire and attachment, captures addiction surprisingly well. So well, in fact, that addiction comes off looking like a fundamental aspect of the human condition.

To prepare for the meeting [with the Dalai Lama], I’ve been trying to think like a Buddhist for the last few months. And what strikes me most is that the Buddhist perspective on personal suffering, based as it is on desire and attachment, captures addiction surprisingly well. So well, in fact, that addiction comes off looking like a fundamental aspect of the human condition.

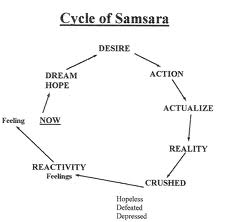

Buddhism sees attachment, craving, and loss as a cycle — a self-perpetuating cycle — in which we chase our own tails and lose sight of everything else. What Buddhists describe as the lynchpin of human suffering, the one thing that keeps us mired in our attachments, is exactly what keeps addicts addicted. The culprit is craving and its relentless progression to grasping. First comes emptiness or loss, then we see something attractive outside ourselves, something that promises to fill that loss, and we crave it. And the next thing we do is grasp — reach for it. Grasping leads to getting: a brief moment of pleasure or relief that reinforces the attachment. But it’s never enough, we crave more, and that’s what keeps the wheel going round. Whether the goal is success, material comfort, prestige — the more respectable human pursuits — or whether it’s heroin, cocaine, booze, or porn, hardly seems to matter. Either way, you’ve locked your sites on an antidote to uncertainty, a guarantee of completeness, when in fact we never become complete by chasing after what we don’t have. And, incredibly, the pursuit itself is the condition for more suffering. Because we inevitably come up empty, disappointed, and betrayed by our own desires.

Now that sounds a lot like addiction to me. Yet the Buddhists are talking about normal seeking and suffering. Isn’t addiction something abnormal? What about all those brain changes I mentioned? [which took up the first half of the paper.] Those brain changes suggest to most scientists and practitioners that addiction is a disease — an unnatural state. But a Buddhist perspective might cast it quite differently, as a particularly onerous outcome of a very normal process, a sadly normal process: our sometimes desperate attempts to seek fulfillment outside ourselves.

So what about those brain changes?

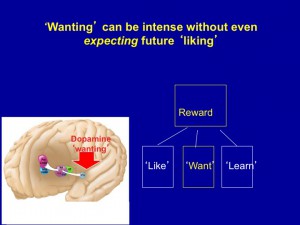

It turns out that the brain is designed to change. Every advance in child and adolescent development requires the brain to change. The condensation of value and meaning in adolescence corresponds with the loss of about 30% of the synapses in some regions of the cortex. As with addiction, normal development involves a lasting commitment to a small set of goals: I’m going to make money, I’m going to live in a secure neighborhood, I’m going to find a life partner. And that involves the formation and consolidation of new neural networks at the expense of older ones. In fact, every episode of learning, whether to play a violin, move in a wheelchair, or see with your fingers after going blind, requires the growth of new synaptic networks. Such cortical changes ride on waves of dopamine, in normal development as in addiction. Gouts of dopamine, with its potency to narrow attention and grow synapses, are highly familiar to lovers and learners alike. That palpable lurch for sex, admiration, or knowledge is always dopamine driven. The brains of starving animals are transformed by dopamine, when, as in addiction, there’s just one goal worth pursuing. And successful politicians achieve dopamine levels that would make an addict swoon. The brain evolved to connect desire and acquisition, wanting and getting, and that connection depends on the tuning of synaptic networks to a narrow range of goals with the help of dopamine.

For both normal development and addiction, desire acts as a carving tool, collapsing neural flexbility in favor of fixed goals. So our understanding of addiction may benefit more from a Buddhist-style perspective on normal development — with its tendency to become fixated on attractive goals — than the disease model favored by Western scientists and doctors. Yet the Buddhist perspective offers another advantage: an emphasis on the value of mindfulness and self-control to free ourselves from unnecessary attachments.

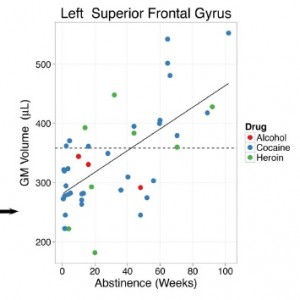

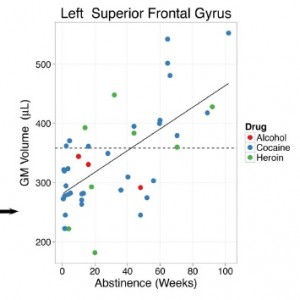

On that note, I’ll end by touching on a provocative experiment recently published in PLOS1, a prominent scientific journal [and brought to my attention by Shaun Shelly on this blog]. It’s well known that cocaine addiction causes reduced grey matter (GM) volume — thought to represent a loss of synapses — in certain regions of the cortex. But these  researchers found increasing synaptic thickness in cocaine addicts who had abstained for several months: and the longer the period of abstention, the greater the growth. Most striking of all, the new growth wasn’t simply a reversal of what was lost, like a pruned bush growing back its leaves. Rather, synaptic growth was observed in new areas — areas known to underlie reflectivity and self-control. In fact, this growth surpassed levels reached by “normal” (never-addicted) people after a period of 8-9 months, indicating the emergence of more advanced mental skills. If these results are replicated, they’ll provide solid evidence that recovery, like addiction, is a developmental process, which may benefit from the advanced cognitive capacities facilitated by mindfulness training.

researchers found increasing synaptic thickness in cocaine addicts who had abstained for several months: and the longer the period of abstention, the greater the growth. Most striking of all, the new growth wasn’t simply a reversal of what was lost, like a pruned bush growing back its leaves. Rather, synaptic growth was observed in new areas — areas known to underlie reflectivity and self-control. In fact, this growth surpassed levels reached by “normal” (never-addicted) people after a period of 8-9 months, indicating the emergence of more advanced mental skills. If these results are replicated, they’ll provide solid evidence that recovery, like addiction, is a developmental process, which may benefit from the advanced cognitive capacities facilitated by mindfulness training.

Based on studies such as these, and filling in the blanks with subjective accounts, addicts, scientists, and contemplatives have a lot to learn from each other. I hope that this theme will help guide the discussion with the Dalai Lama in October. Ater all, addicts and meditators make use of the same brain, with all its vulnerabilities and strengths. It makes sense that the brain changes underlying suffering and healing have much in common, whatever their source.