My blogging days may be winding down. But if they do, as they do, I want to put more energy into methods for helping beat addiction than ideas for explaining it. It’s critical to understand addiction in depth, and I still believe that linking neuroscience with lived experience provides a potent frame of reference. But lately I’ve been moving on, thinking almost exclusively about treatment. Is there a connection from brain parts to mind parts to effective methods for helping people? Let’s see.

I started this blog with an emphasis on addiction neuroscience. I can sum up most of that brain stuff in a few simple conclusions, but I’m going to add some points of clarification:

-even though brains change with addiction, addiction is not a brain disease, as often claimed. The brain changes with any and all learning, and the more emotional and repetitive the learning events, the greater and more enduring the resulting brain changes.

-habits are inscribed in synaptic networks (networks of connections among neurons). Those networks become the hardware for processing new information: “What fires together wires together.” Thus, novelty gets sidelined by habitual patterns of thought, feeling, and behaviour. That’s the case with love, politics, religion, and yes, addiction.

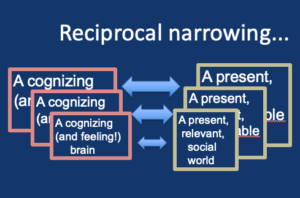

-the “narrowing” of synaptic networks is mirrored by a narrowing of the social world. Friends, family, finances, legal circumstances all become more limited, more “narrow,” for the person who finds fewer neural avenues for pursuing rewards. You’ve heard that life imitates art? It’s also the case that social change imitates brain change. (See my review article here.)

-the “narrowing” metaphor suggests that the connections between different brain parts become more entrenched, less open to change. But that doesn’t mean that diverse neural regions become fused in some way. The brain retains its functional components (e.g., frontal regions underlying conscious attention versus limbic structures in charge of automatic behaviour) and those components are designed to compete.

So now what? With all we know about the science and psychology of addiction, how do we put it all together? How do we help?

The neuropsychology of addiction is important! It exposes us to many critical concepts, like the biological embedding of habit formation. Yet we don’t generally treat addiction, either in ourselves or others, by altering the brain. At least not directly. We don’t perform lobotomies or lobectomies, nor is it common to use deep-brain stimulation or transcranial magnetic stimulation to help people recover. No, when it’s time to turn from thinking to helping, we turn to talk, often in the form of psychotherapy.

Talk is social behaviour. So the goal is to free up addicted people by expanding their social world, especially the social world they carry around in their minds — the way they talk to themselves, the way they interpret messages from others. At that point the neuropsychology of addiction takes a back seat, as an aid to our clinical intuitions and our capacity to listen. Once again, lived experience, both that of the client and of the therapist, becomes the needed partner for our scientific theories.

Now if both the brain and the social world “shrink” in tandem, then we should be able to “grow” the brain (the realm of synaptic possibilities) by “growing” social-psychological flexibility. How can this be achieved?

(There is one method of acting on the brain directly, bypassing all that messy talk stuff. We can give the addicted person drugs that directly affect their neurophysiology and/or how they think and feel. Antidepressants and antianxiety drugs to target underlying mood states, methadone or naltrexone to nudge drug-soaked synapses out of their ruts. But in my view, psychotherapy — if it works — goes deeper, induces changes that last longer, and provides a sense of well-being that no drug can mimic.)

I find Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy to be the most effective form of talk therapy available. You’ve heard me rave about it over the last few posts. I’ll end today by pointing out that IFS brings to the table a fundamental experience that most addicts find exhaustingly familiar. For them (and of course I include myself) the internal social world, the voices in our heads, are most conspicuous because they are at war with each other. The internal critic tells you that your wishes and goals are reprehensible. But the childish wishes don’t go away. In fact, they get stronger, fueled by defiance against the internal critic and desperation to meet needs that are hunted down and locked away.

By recognizing this internal duality, this multiplicity of conflicting part-selves, IFS brings empathy and clinical intuition to bear on what neuroscientists already know but never think about. Brains are composed of components that are designed (by evolution) to compete with each other. Frontal inhibition (lateral prefrontal cortex) versus learned habits (striatum), future oriented action tendencies (dorsal cortical circuits) versus preoccupation with threats (ventral cortex and amygdala). These tendencies are supposed to compete. That’s what gives humans their incredible capacity for choice and intelligent action.

How did we psychologists forget that when going about devising treatment strategies?

So, here’s the breath of fresh air provided by IFS. Conventional methods of treating addiction involve training people to “just say No.” That doesn’t work. Mounds of disappointing outcome stats make that clear. Why doesn’t it work? Because it ignores the lived experience of people in addiction and it ignores the way brains actually work. In contrast, IFS trains people to listen to the voices or “parts” that occupy their minds and accept them, welcome them, soothe them, without trying to shut them down. In that sense, it respects the idea that the mind — as well as the brain — is multiple, and it is composed of competing functions.

But that’s enough for today. In my next post I want to be very explicit about the IFS alternative to “Just say No.”

included a very sad girl who could not give up her preoccupation with the tragedy of her life (which hinged on her mother’s rejection and self-denigration). Much of Maya’s internal conflict triggered excessive waves of grief and self-rebuke. It would take up too much time and space to explore these themes in a blog post. It took a lot of time to discover them in therapy. But meanwhile, Maya kept drinking large amounts of cheap wine, almost every night, wrecking her health, and reinforcing her sense of hopelessness. It seemed urgent to find an exercise that could help, with me or without me, starting now.

included a very sad girl who could not give up her preoccupation with the tragedy of her life (which hinged on her mother’s rejection and self-denigration). Much of Maya’s internal conflict triggered excessive waves of grief and self-rebuke. It would take up too much time and space to explore these themes in a blog post. It took a lot of time to discover them in therapy. But meanwhile, Maya kept drinking large amounts of cheap wine, almost every night, wrecking her health, and reinforcing her sense of hopelessness. It seemed urgent to find an exercise that could help, with me or without me, starting now. than perceptions, thoughts, and bodily sensations. Follow the emotions, surf them, watch them come and go, don’t think about them too much. You might expect oodles of shame and anxiety. Practice your ability to discern, because some of these emotions might be so common that they seem like background noise. There may also be streaks of unexpected emotions, such as bolts of anger when you thought you were generally “nice”. With emotions like anger and fear, which have a definite object, try to be aware of who/what that object is. Is it self or other? Stay at the surface of awareness. Don’t “go deep.” Let the emotions come to you. You don’t have to go hunting.

than perceptions, thoughts, and bodily sensations. Follow the emotions, surf them, watch them come and go, don’t think about them too much. You might expect oodles of shame and anxiety. Practice your ability to discern, because some of these emotions might be so common that they seem like background noise. There may also be streaks of unexpected emotions, such as bolts of anger when you thought you were generally “nice”. With emotions like anger and fear, which have a definite object, try to be aware of who/what that object is. Is it self or other? Stay at the surface of awareness. Don’t “go deep.” Let the emotions come to you. You don’t have to go hunting. 2. Notice that each emotion may be felt by one or more parts. Which part is revving up now? Anger might go with the harsh internal critic, but anger might also go with the defiant “fuck you” rebel part. Get a sense of which part is becoming activated. Shame probably goes with a very young part — perhaps a part that (in IFS terms) remains an exile…not fully conscious, perhaps actively shunned or rejected. Anxiety also may be felt by young “exiles” — cringing, alone, scared, helpless — or by “managers” (e.g., parts who organize, take care, or judge) when they sense that they’re losing control. These managers can also be young. (A deeper discussion of what these parts actually are has to await a later post.)

2. Notice that each emotion may be felt by one or more parts. Which part is revving up now? Anger might go with the harsh internal critic, but anger might also go with the defiant “fuck you” rebel part. Get a sense of which part is becoming activated. Shame probably goes with a very young part — perhaps a part that (in IFS terms) remains an exile…not fully conscious, perhaps actively shunned or rejected. Anxiety also may be felt by young “exiles” — cringing, alone, scared, helpless — or by “managers” (e.g., parts who organize, take care, or judge) when they sense that they’re losing control. These managers can also be young. (A deeper discussion of what these parts actually are has to await a later post.) 3. The last step is to act on this internal world, i.e., to guide it as it evolves and changes. This way of framing things deviates from IFS orthodoxy, but the underlying goal and the net effect could be almost identical. Now comes the sense of being a coach…or even a parent. IFS stresses the power of the Self — “Self” with a capital “S”. That’s the part that’s not a part. The Self is viewed as a compassionate, perceptive and aware place within oneself — a centre — that recognizes and accepts the various parts along with their needs and concerns (e.g., their emotions,

3. The last step is to act on this internal world, i.e., to guide it as it evolves and changes. This way of framing things deviates from IFS orthodoxy, but the underlying goal and the net effect could be almost identical. Now comes the sense of being a coach…or even a parent. IFS stresses the power of the Self — “Self” with a capital “S”. That’s the part that’s not a part. The Self is viewed as a compassionate, perceptive and aware place within oneself — a centre — that recognizes and accepts the various parts along with their needs and concerns (e.g., their emotions,  their goals). So, from this place, you can soothe the anxious child, comfort him or her so there won’t be so much loneliness or dread. You can also connect with the Firefighter, and coax it (in a friendly way) to relax, to look before leaping for that bottle or that pipe. You can help antagonistic parts disengage, lay down their arms for awhile. For example, judging, critical parts can be asked to back off: we can tell them we appreciate their vigilance, but they’re coming on too strong and it’s not helping (e.g., too much shame, augmenting the Firefighter’s urge to drink or take drugs).

their goals). So, from this place, you can soothe the anxious child, comfort him or her so there won’t be so much loneliness or dread. You can also connect with the Firefighter, and coax it (in a friendly way) to relax, to look before leaping for that bottle or that pipe. You can help antagonistic parts disengage, lay down their arms for awhile. For example, judging, critical parts can be asked to back off: we can tell them we appreciate their vigilance, but they’re coming on too strong and it’s not helping (e.g., too much shame, augmenting the Firefighter’s urge to drink or take drugs).

The first and perhaps biggest step is to start a dialogue with the part of us that does the escaping. They call it the Firefighter, because its job is to put out the fire of anxiety and self-abuse, as quickly and as effectively as possible, with no regard for the mess it leaves behind. We’re used to reviling that part: that pernicious, irresponsible urge to get loaded, high, smashed. That part is almost always the object of criticism (both from ourselves and from others).

The first and perhaps biggest step is to start a dialogue with the part of us that does the escaping. They call it the Firefighter, because its job is to put out the fire of anxiety and self-abuse, as quickly and as effectively as possible, with no regard for the mess it leaves behind. We’re used to reviling that part: that pernicious, irresponsible urge to get loaded, high, smashed. That part is almost always the object of criticism (both from ourselves and from others). Wearing her sexiest clothes, with a cigarette dangling from her lips, she’d hang out with other teens on the street corner. There was drinking, and smoking, cannabis, and sex. Piya took over at night, with the express purpose of having fun, feeling free, and saying Fuck You! to the authorities that ruled Maya’s life.

Wearing her sexiest clothes, with a cigarette dangling from her lips, she’d hang out with other teens on the street corner. There was drinking, and smoking, cannabis, and sex. Piya took over at night, with the express purpose of having fun, feeling free, and saying Fuck You! to the authorities that ruled Maya’s life. In our therapy, guided by IFS principles, I encourage Maya to do two things: first, notice that Piya is made to feel dirty and blameworthy by a critical voice in her own head. She calls the critical part Madam Z (…not her real made-up name. Yes, even internal voices need pseudonyms) who has the character of a strict school teacher or aunt. Madam Z has much to contribute. We don’t want to banish her. But we don’t need her badgering Piya every time she appears. The second thing is to engage with Piya, not from the perspective of Madam Z but from the perspective of

In our therapy, guided by IFS principles, I encourage Maya to do two things: first, notice that Piya is made to feel dirty and blameworthy by a critical voice in her own head. She calls the critical part Madam Z (…not her real made-up name. Yes, even internal voices need pseudonyms) who has the character of a strict school teacher or aunt. Madam Z has much to contribute. We don’t want to banish her. But we don’t need her badgering Piya every time she appears. The second thing is to engage with Piya, not from the perspective of Madam Z but from the perspective of  Maya’s peaceful, accepting self. Her compassionate core — what IFS calls Self with a capital-S. That Self becomes more present, more tangible, when Maya takes a few minutes to do some deep breathing, to feel what it’s like simply to be inside her own body, alive and perceptive. Ironically or mysteriously, this Self may the same thing as

Maya’s peaceful, accepting self. Her compassionate core — what IFS calls Self with a capital-S. That Self becomes more present, more tangible, when Maya takes a few minutes to do some deep breathing, to feel what it’s like simply to be inside her own body, alive and perceptive. Ironically or mysteriously, this Self may the same thing as  To forgive and embrace the part that’s simply waiting for a chance to get stoned…that’s radical. It flies in the face of conventional approaches to addiction, which demand that we get rid of this part, cast it out, or at least ignore it until it finally shuts up. So what’s the result? Doesn’t that just give us permission to get stoned more often, to drink more, to fully surrender to the addictive impulse? To do more push-ups in the parking lot (an infamous 12-step slogan).

To forgive and embrace the part that’s simply waiting for a chance to get stoned…that’s radical. It flies in the face of conventional approaches to addiction, which demand that we get rid of this part, cast it out, or at least ignore it until it finally shuts up. So what’s the result? Doesn’t that just give us permission to get stoned more often, to drink more, to fully surrender to the addictive impulse? To do more push-ups in the parking lot (an infamous 12-step slogan).