Following that invitation to meet with the Dalai Lama, I’ve been looking more into Buddhism and studies that link it with neuroscience – and with addiction. In one recent article, I learned that mindfulness/meditation (let’s call it MM) changes the brain in one important way. From the treatment community, we also know that MM helps people recover from addiction. Research has been sparse so far, but there are good results with respect to smoking. So my question is this: if we know that MM changes the brain in such and such a way, and if we know that it helps reduce addiction, will we come to understand what neural processes are at the core of addiction?

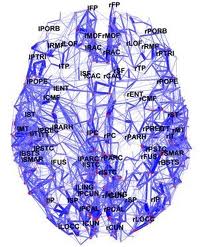

An important brain region has been identified in many labs in the last few years. It’s called the Default Mode Network. This area (which includes the posterior cingulate and medial PFC) “lights up” when we are daydreaming, self-reflecting,  imagining our selves in past or future situations, or imagining interactions with other people. In other words, the default mode is where we go when we are going with the flow and thinking in an undirected way about ourselves. Most interesting is that the default mode network turns off when we become focused on a task. When we have to do something novel or challenging, we leave the default mode and enter a focused mode, supported by very different brain regions, including the dACC – a region I’ve discussed as critical for self-control.

imagining our selves in past or future situations, or imagining interactions with other people. In other words, the default mode is where we go when we are going with the flow and thinking in an undirected way about ourselves. Most interesting is that the default mode network turns off when we become focused on a task. When we have to do something novel or challenging, we leave the default mode and enter a focused mode, supported by very different brain regions, including the dACC – a region I’ve discussed as critical for self-control.

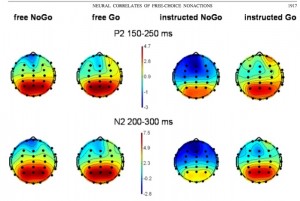

This particular article shows that MM changes activity in the Default Mode Network – a finding supported by other studies. The more you meditate or practice mindfulness, the more likely you are to activate the “focused” brain regions and turn off the default mode, especially when you’re required to pay attention. This article also claims that the reason MM helps people recover from addiction is because addicted individuals have too much activation of the default mode network. In other words, the images, cues, plans, ideas, associations, etc, that come to your mind when you’re addicted are more like daydreaming than focusing. You are using a brain region that DOES NOT solve problems but maintains a habitual sense of who you are.

I found just two articles that show that addicts have more activation in the Default Mode Network than other people – not a huge number of studies so far, but still… One of these showed that the default mode network is highly activated in heroin addicts, and this activation does not go down when they’ve had a dose of methadone. So whether you’re high or not, this is home base.

I’ve usually considered addiction as being too focused. After all, craving – the main ingredient of addiction – means having one goal and only one goal consistently at the centre of your attention. But it’s also true that there’s something very unfocused about addiction. Your thoughts are following such familiar ruts, without conscious guidance, and your sense of yourself is habitual rather than flexible. Oh wouldn’t it be nice if…..here I go again…not too surprising….well I don’t have to quit this week….could wait till things get less stressful, etc, etc. So maybe that unfocused state is where the addictive plan starts to form. Look at this snatch from John’s Guest Memoir:

Resting after the first set [of exercises]; I do something I should not do: I trace with my finger along a raised vein on the back of my forearm, slowly, gently, slightly, thinly smiling — the blood’s rushing to my head already anyway — tap on that one good spot a couple times, and now here comes the idea. Ohhhh… and oh fuck that reminds me of the dream I had last night.

That pretty much typifies the default mode…not paying attention, letting your thoughts go, which includes letting them go to places where they really should not go.

So, if addictive behaviour arises from a brain network that supports habitual, undirected thoughts, and if MM helps bring focus and clarity to one’s thinking, by deactivating that network, then it wouldn’t be surprising that MM is an important tool for recovery. And this kind of research, which is starting to grow exponentially, teaches us critical lessons about how treatment can tackle addiction – right in the middle of our brains.