Last post I shared a conundrum with you. I’d written a chapter for a book for addiction doctors. But when I learned the title of the book I decided (after all that work!) to withdraw it. Was that the right thing to do? Your comments convinced me it wasn’t.

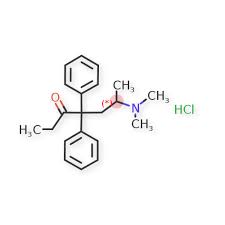

My chapter urged practitioners to view addiction as a learned habit, not a disease, and showed show how the brain changes corresponding with addiction fit our understanding of learning rather than pathology. And it seemed compatible with a book that was supposed to “create space for clinicians to go beyond narrow guidelines….to reflect more of the ‘art’ of working within addiction medicine.” I thought my chapter would fit right in.

Until I read the proposed title: A prescriber’s guide to methadone and buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. How could a “prescriber’s guide” advocate moving beyond conventional guidelines? At best I’d have to rewrite the thing. And even then, my whole argument for moving beyond the “disease label” starts to unravel when it comes to the prescription pad. (see last post for details) In sum, my chapter in this book would be a sellout! Not just a poor fit but a surrender to the opposition!

That’s where you guys came in. I asked commenters to give me the benefit of your perspectives, and that’s what you did. There were good arguments on both sides, but a majority of you articulated good reasons why I should have left the chapter in.

For example, Matt had this to say: “I don’t quite understand why you would not offer your unique perspective to anyone, especially physicians, and especially since they asked for the chapter to begin with. There are so many physicians who would be exposed to your ideas who may have had no idea they existed.”

For “my ideas,” read “progressive conceptualizations of addiction that step around medicalization.”

Annette wrote that “your role is, undoubtedly, to EDUCATE. The world is shifting…Mental health advocates are talking openly about the impact of social, economic and political structures on our (fragile) mental health, so those of us who understand this need to keep educating.”

But Shaun came up with the coup de gras: “I imagine two scenarios,” he wrote. “ONE: a well-meaning doctor who has learned it all from the book of NIDA, Chapter Volkow, TIP63: Patient has life-long disease of brain that compromises free-will. They will manipulate and lie. I will insist that they pee in a cup [and] have medication discontinued if they test positive… Chance of getting on with life, zero.

“TWO: Having read Marc’s chapter, start by seeing a person who, for whatever reason, has learned to use heroin as a valid way dealing with life. Through collaboration and honest dialogue, with voluntary additional services that they may or may not request, I will prescribe their methadone without fuss and making them seem like I’m doing them the world’s biggest favour. I will…not wield [my] autonomy like a weapon…I would…’provide a scaffolding’ of methadone ‘to support a vision of future self,’ rather than use methadone as a straight jacket to constrict their right to breathe.”

(I suggest you to read these comments in their entirety.)

When I read Shaun’s comment I was still reeling from a psychotherapy session I’d had with Sally (fictitious name) a few hours earlier. I’d been meeting (online) with this fortiesh English woman for psychotherapy every week or two for about eight months, during which time I’ve tried to help her get on with her life, make peace with her demons and self-doubts, and keep her codeine habit within safe limits. This session she talked about her years of heroin addiction and hooking. It wasn’t the first time, but the level of detail, the pain she expressed so vividly, made me more aware than ever of the grinding inhumanity of the life she’d lived.

How did Sally get into heroin? When she was 14, a teacher at the children’s home began touching her genitals. She wasn’t angry at the time, she says, but her perception of adults changed entirely from that point on. A couple of months

How did Sally get into heroin? When she was 14, a teacher at the children’s home began touching her genitals. She wasn’t angry at the time, she says, but her perception of adults changed entirely from that point on. A couple of months  later, a math teacher–she remembers him as being very old, with bad teeth–started making advances. This time, she threw a chair at him. She got kicked out of school for her troubles, and that’s when she got to know Mike, who introduced her to heroin.

later, a math teacher–she remembers him as being very old, with bad teeth–started making advances. This time, she threw a chair at him. She got kicked out of school for her troubles, and that’s when she got to know Mike, who introduced her to heroin.

Sally had a pattern of running out of one children’s home and landing in another. She hated them all, she told me. Her parents came to visit her often enough, but they didn’t take her home with them. Maybe that was the problem. Her mom had told her she couldn’t handle her  tom-boy ways. Sally liked looking for bugs under rocks rather than dressing nicely. That’s just Sally being Sally, the family concluded. And she became an outsider in her own home. By adolescence she’d often end up swearing at her mom, sniffing glue and hanging out with the wrong kids on the corner.

tom-boy ways. Sally liked looking for bugs under rocks rather than dressing nicely. That’s just Sally being Sally, the family concluded. And she became an outsider in her own home. By adolescence she’d often end up swearing at her mom, sniffing glue and hanging out with the wrong kids on the corner.

So it was the usual culprits: inadequate parenting, child abuse, growing up without any real protection…Sally’s credentials for drug use would include a pretty high ACE score. But Mike was the catalyst.

He started off as her friend, someone to love her and listen to her. Then he became her pimp, demanding that she go out and find money to score more dope. Her young body was all that stood between his well-being and withdrawal symptoms. He’d beat her up if she refused–broken ribs, a couple of teeth knocked out– except when he got worried about damaging the merchandise.

He started off as her friend, someone to love her and listen to her. Then he became her pimp, demanding that she go out and find money to score more dope. Her young body was all that stood between his well-being and withdrawal symptoms. He’d beat her up if she refused–broken ribs, a couple of teeth knocked out– except when he got worried about damaging the merchandise.

Sally’s life stabilized after all. She went out at night, looked for men, got the money up front, until she had enough to score. Then went back to Mike and shot up. This went on for years. Her mother saw her  once, sitting at a street corner, head lolling back, almost unrecognizable because she was so thin. But she just kept driving. That’s just Sally being Sally. Skeletal and bruised, waiting for a man degraded enough to look past the bruises for 20 minutes of warmth. That’s who she became. Until she was rescued by a man who got her off dope, as long as she’d never look at another man again.

once, sitting at a street corner, head lolling back, almost unrecognizable because she was so thin. But she just kept driving. That’s just Sally being Sally. Skeletal and bruised, waiting for a man degraded enough to look past the bruises for 20 minutes of warmth. That’s who she became. Until she was rescued by a man who got her off dope, as long as she’d never look at another man again.

The real story of Sally’s addiction is so diametrically opposite anything resembling a disease. The web of social, economic, and familial factors, the absence of a social safety net, the play-it-safe inclination of child-welfare services that weren’t interested in the child’s version of events. That’s where the problem arose. So where was it to be solved? In a doctor’s office? In a methadone clinic?

The real story of Sally’s addiction is so diametrically opposite anything resembling a disease. The web of social, economic, and familial factors, the absence of a social safety net, the play-it-safe inclination of child-welfare services that weren’t interested in the child’s version of events. That’s where the problem arose. So where was it to be solved? In a doctor’s office? In a methadone clinic?

At least once a year someone would demand sex without pay or else they’d hurt her, badly, they warned. And she’d have to “service” this man anyway, get it over with as soon as possible, because the night was wearing on. There weren’t many hours left to find a paying customer. And she needed to buy heroin. Her stomach was already knotting, her muscles cramping, the nausea rising. She couldn’t face it, not tonight. She couldn’t face Mike empty-handed and she had nowhere else to go.

Sally told me that she’d cry every day, even once her life had moved on. She just couldn’t process all she’d been through. Now, today, I couldn’t shake my own grief. That’s when I read Shaun’s comment. And that’s when I realized I should have submitted my chapter after all.

The horror of Sally’s circumstances could have been prevented if opiate substitutes had been available, without prohibitive costs, without further degradation. She would have left Mike, would have left the street, if she could have found a way out.

I’m not beating myself up about it, but I made a mistake. My reluctance wasn’t wrong. The “prescriber’s” shingle unfortunately strengthens the inclination to make OST (opioid substitution therapy) the goal of addiction treatment. It was my decision to withhold the chapter that was wrong.

I should have contributed the chapter to help doctors see OST as scaffolding, a means to an end, rather than an end in itself. That way, the social-developmental roots of (psychological) addiction and the doggedness of physiological dependency could have been specified as parallel aspects of an opioid habit, distinct but convergent, making it all the more insidious. Both are real. Both may need to be challenged head-on. And there’s no universal formula for which should come first.

Now about that chapter. I’ve had papers rejected by publications lots of times. It’s part of the rat race of being an academic, a researcher, submitting your best work to journals, waiting for the letter from the editor, finally getting that heart-stopping email and reading it and Oh Shit! They’re rejecting it?! Without even a “revise and resubmit!” Damn ignorant asshole editors. Too good for your shitty journal anyway… Then the anger and disappointment start to evaporate and you start thinking about what journal to send it to next. That’s the life of an academic. And that’s one reason I was glad to be done with it, and why, about eight months ago, I swore to myself I was done with academic writing.

Now about that chapter. I’ve had papers rejected by publications lots of times. It’s part of the rat race of being an academic, a researcher, submitting your best work to journals, waiting for the letter from the editor, finally getting that heart-stopping email and reading it and Oh Shit! They’re rejecting it?! Without even a “revise and resubmit!” Damn ignorant asshole editors. Too good for your shitty journal anyway… Then the anger and disappointment start to evaporate and you start thinking about what journal to send it to next. That’s the life of an academic. And that’s one reason I was glad to be done with it, and why, about eight months ago, I swore to myself I was done with academic writing. So I wrote the chapter. Took pieces from other work, revised them, wrote some new stuff, trying to make it accessible for all those doctors out there, because they don’t really understand human development very well and they sure don’t understand psychology very well. So, why not give them the benefit of my stratospheric perspective. (LOL) I spent a couple of weeks working pretty hard, sent it in, and soon heard back from the editor. Thank you for submitting your chapter for publication in “A prescriber’s guide to methadone and buprenorphine for opioid use disorder…” Which is when I said to myself, those ignorant editors! They got the wrong book. Or the wrong title. Or something. I can’t write a chapter that urges ditching the medical model for a damn prescriber’s guide!

So I wrote the chapter. Took pieces from other work, revised them, wrote some new stuff, trying to make it accessible for all those doctors out there, because they don’t really understand human development very well and they sure don’t understand psychology very well. So, why not give them the benefit of my stratospheric perspective. (LOL) I spent a couple of weeks working pretty hard, sent it in, and soon heard back from the editor. Thank you for submitting your chapter for publication in “A prescriber’s guide to methadone and buprenorphine for opioid use disorder…” Which is when I said to myself, those ignorant editors! They got the wrong book. Or the wrong title. Or something. I can’t write a chapter that urges ditching the medical model for a damn prescriber’s guide! me after I withdrew my submission and said: Addiction doctors prescribe opioid substitutes to 95% of their opioid-addicted patients. Like: duh…didn’t I know that? Yes, I knew that, more or less. And I knew that

me after I withdrew my submission and said: Addiction doctors prescribe opioid substitutes to 95% of their opioid-addicted patients. Like: duh…didn’t I know that? Yes, I knew that, more or less. And I knew that  opioid addicts are often in desperate need of opioid substitution therapy (OST). It helps them get off the street and sometimes stay off, it relieves the overwhelming anxiety of withdrawal, and it saves lives. As

opioid addicts are often in desperate need of opioid substitution therapy (OST). It helps them get off the street and sometimes stay off, it relieves the overwhelming anxiety of withdrawal, and it saves lives. As  all that. I fully advocate the use of methadone and Suboxone. I agree with other progressive addiction specialists (e.g.,

all that. I fully advocate the use of methadone and Suboxone. I agree with other progressive addiction specialists (e.g.,  I told myself I’m trying go avoid an awkward irony: that there’s maybe one good reason to call addiction a disease. In the US and Canada it’s the only way to get addicts their medicine, their heroin substitutes. I’ve thought about this

I told myself I’m trying go avoid an awkward irony: that there’s maybe one good reason to call addiction a disease. In the US and Canada it’s the only way to get addicts their medicine, their heroin substitutes. I’ve thought about this  lots. But I remain concerned and confused. Maybe “medicalization” is the best we can do for people who are in a real jam, on the street or close to it, hunting for heroin day by day. Yet it maintains, in fact it strengthens, the premise that these people are sick, and it sidelines all the familial, social, economic, and cultural forces that pushed them into that lifestyle in the first place.

lots. But I remain concerned and confused. Maybe “medicalization” is the best we can do for people who are in a real jam, on the street or close to it, hunting for heroin day by day. Yet it maintains, in fact it strengthens, the premise that these people are sick, and it sidelines all the familial, social, economic, and cultural forces that pushed them into that lifestyle in the first place.

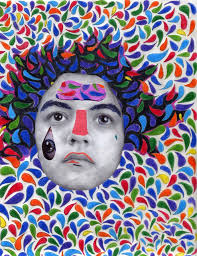

With addiction, you think this thing, this substance (let’s say a few lines of coke) is valuable and special. And you feel the excitement of anticipation — soon I’m gonna have some. Then you feel the buzz, and doesn’t that feel great? Which strengthens the image, the conception, that coke is valuable and special. See how the thought/image and the feeling (both before and during) fuel each other? Which is why it’s so hard to say No thanks, not tonight.

With addiction, you think this thing, this substance (let’s say a few lines of coke) is valuable and special. And you feel the excitement of anticipation — soon I’m gonna have some. Then you feel the buzz, and doesn’t that feel great? Which strengthens the image, the conception, that coke is valuable and special. See how the thought/image and the feeling (both before and during) fuel each other? Which is why it’s so hard to say No thanks, not tonight. So what does the addictive substance or act symbolize? To me, that’s the big question. The longer I practice psychotherapy with people in addiction, the more convinced I am that each person constructs his or her own scenario, vignette, drama, diorama — I don’t know what to call it — based on what went wrong or what went missing in childhood or adolescence. I introduced this idea last post, in terms of diving into the child self-narrative. Here I want to get into the details: what’s the narrative about?

So what does the addictive substance or act symbolize? To me, that’s the big question. The longer I practice psychotherapy with people in addiction, the more convinced I am that each person constructs his or her own scenario, vignette, drama, diorama — I don’t know what to call it — based on what went wrong or what went missing in childhood or adolescence. I introduced this idea last post, in terms of diving into the child self-narrative. Here I want to get into the details: what’s the narrative about? she was achingly lonely. But when she went into her closet and cut little red lines in her forearm, she felt free, she felt vital, she was unobserved, she didn’t need or seek permission, she felt defiant, and most of all she felt in control of her own feelings. That’s what the cutting meant to her then. And that’s almost exactly what coke means to her now, decades later.

she was achingly lonely. But when she went into her closet and cut little red lines in her forearm, she felt free, she felt vital, she was unobserved, she didn’t need or seek permission, she felt defiant, and most of all she felt in control of her own feelings. That’s what the cutting meant to her then. And that’s almost exactly what coke means to her now, decades later.  She scampers into the bathroom, leaving the other ladies chatting over wine or coffee, and does a couple of lines. Again, she’s on her own, released, free, defiant, and in control of what she’s feeling. Now take that symbolic scenario she’s created, and graft it onto the feeling of the anticipation and then the feeling of the rush itself. That cognition-emotion linkage has been reinforced thousands of times. It’s not going to go away easily.

She scampers into the bathroom, leaving the other ladies chatting over wine or coffee, and does a couple of lines. Again, she’s on her own, released, free, defiant, and in control of what she’s feeling. Now take that symbolic scenario she’s created, and graft it onto the feeling of the anticipation and then the feeling of the rush itself. That cognition-emotion linkage has been reinforced thousands of times. It’s not going to go away easily. with my armful of chips. Now couple that image with the sheer excitement of not knowing how the next hand will turn out. (That’s a big deal for gamblers.) The image and the feeling fuse — possibly forever.

with my armful of chips. Now couple that image with the sheer excitement of not knowing how the next hand will turn out. (That’s a big deal for gamblers.) The image and the feeling fuse — possibly forever. A couple of my clients have combined drugs, sex or sexting, and/or porn into this incredibly artful (what else to call it?) ritual — a scenario in which they are desirable, desired, potent, free, and safe. The experience they’re addicted to is basically a fantasy of being both very good and very bad, nasty and safe at the same time — the dream fantasy of a child or young teenager. But here’s the thing: the components — the coke and the porn for example — are only valuable in how they contribute to this symbolic amalgam. What each offers, without that symbolic currency, is almost nothing at all.

A couple of my clients have combined drugs, sex or sexting, and/or porn into this incredibly artful (what else to call it?) ritual — a scenario in which they are desirable, desired, potent, free, and safe. The experience they’re addicted to is basically a fantasy of being both very good and very bad, nasty and safe at the same time — the dream fantasy of a child or young teenager. But here’s the thing: the components — the coke and the porn for example — are only valuable in how they contribute to this symbolic amalgam. What each offers, without that symbolic currency, is almost nothing at all. So I’ve got a prescription for some pretty powerful opioids. And as soon as I pop one or two, the whole symbolic vignette from my days of addiction returns. I get to make myself warm and safe, I get to be taken care of, like when I was sick as a child — come here, Mommy, I need you — and I get to control all that with

So I’ve got a prescription for some pretty powerful opioids. And as soon as I pop one or two, the whole symbolic vignette from my days of addiction returns. I get to make myself warm and safe, I get to be taken care of, like when I was sick as a child — come here, Mommy, I need you — and I get to control all that with  these little objects — the pills — which are mine! (particularly handy if Mom isn’t feeling very connected). That symbolism is so much more powerful than the feeling the drug provides. Yet the drug does provide a feeling…a warmth in my stomach, a vague but familiar sense of pleasure. What I’m saying is that this feeling is pretty nice (though I know it will collapse into boredom soon enough), but its power lies in how it holds the symbolic scenario in place.

these little objects — the pills — which are mine! (particularly handy if Mom isn’t feeling very connected). That symbolism is so much more powerful than the feeling the drug provides. Yet the drug does provide a feeling…a warmth in my stomach, a vague but familiar sense of pleasure. What I’m saying is that this feeling is pretty nice (though I know it will collapse into boredom soon enough), but its power lies in how it holds the symbolic scenario in place. But man, do I ever get what it’s like, for my addicted clients, and for almost anyone fighting that so-powerful amalgam of thought and feeling: the fabricated scene, the sense of completeness, the revised reality, and the control you take (or at least hope for) — an entrenched (but fantasized) improvement over what it was really like to be young and scared, alone and helpless.

But man, do I ever get what it’s like, for my addicted clients, and for almost anyone fighting that so-powerful amalgam of thought and feeling: the fabricated scene, the sense of completeness, the revised reality, and the control you take (or at least hope for) — an entrenched (but fantasized) improvement over what it was really like to be young and scared, alone and helpless.

expectations. I’d anticipate going home, dismissing my own needs, and catering to hers. Really I was going back to my “false self” — a term borrowed from psychoanalytic theory — which means being fake and imagining that the fake you is the real you. I tried being sensitive, solicitous, responsible, accommodating. I felt trapped in this role — a third self-narrative? I couldn’t see a way out. So I managed to change selves. I’d get those first glimmerings…why don’t I get some drugs and get high and of course hide it, not only from my wife but from everyone. It will be my secret — it’s always been my secret. Except when things went really wrong, like the time I woke up on a

expectations. I’d anticipate going home, dismissing my own needs, and catering to hers. Really I was going back to my “false self” — a term borrowed from psychoanalytic theory — which means being fake and imagining that the fake you is the real you. I tried being sensitive, solicitous, responsible, accommodating. I felt trapped in this role — a third self-narrative? I couldn’t see a way out. So I managed to change selves. I’d get those first glimmerings…why don’t I get some drugs and get high and of course hide it, not only from my wife but from everyone. It will be my secret — it’s always been my secret. Except when things went really wrong, like the time I woke up on a  sofa in the student union lounge suffocating on what seemed poison gas. That unholy smell was burning upholstery. The sofa was on fire from the cigarette I’d dropped while nodding out. Or the times I got busted, fired, or kicked out of school.

sofa in the student union lounge suffocating on what seemed poison gas. That unholy smell was burning upholstery. The sofa was on fire from the cigarette I’d dropped while nodding out. Or the times I got busted, fired, or kicked out of school. Here’s my point: when I switched to my drug-taking self, everything changed in my emotional world. I felt free and I felt real. I knew that I was in deep shit in my life, in my marriage, in every index of adult functioning. But! In this self-narrative, I was a bad boy who would get away with something, as I had before, as I would again, until…maybe until I got caught or until the rules changed. I willingly went after the freedom I gained from “being bad” — which is pretty much the label I attached to my drug-seeking.

Here’s my point: when I switched to my drug-taking self, everything changed in my emotional world. I felt free and I felt real. I knew that I was in deep shit in my life, in my marriage, in every index of adult functioning. But! In this self-narrative, I was a bad boy who would get away with something, as I had before, as I would again, until…maybe until I got caught or until the rules changed. I willingly went after the freedom I gained from “being bad” — which is pretty much the label I attached to my drug-seeking. There’s a lot more to say about this choice. We know that most addicts had difficult childhoods of one kind or another; they could not be the children (or teens) they really were yet fit the world of adult expectations. In the dissociation of self-narratives that comes with addiction, we become those unruly children once again.

There’s a lot more to say about this choice. We know that most addicts had difficult childhoods of one kind or another; they could not be the children (or teens) they really were yet fit the world of adult expectations. In the dissociation of self-narratives that comes with addiction, we become those unruly children once again.

stop trying so hard to unify them? Because sometimes…you just can’t. They simply don’t fit. And the effort to weld them together can be overwhelming, soul-destroying, can leave us feeling more fragmented than we already were. The

stop trying so hard to unify them? Because sometimes…you just can’t. They simply don’t fit. And the effort to weld them together can be overwhelming, soul-destroying, can leave us feeling more fragmented than we already were. The  infamous “dry drunk” is one victim of this misguided struggle.

infamous “dry drunk” is one victim of this misguided struggle. Or who I expect to become — a very different way to frame a future self!

Or who I expect to become — a very different way to frame a future self! to get high, being determined, being defiant about getting high. (Even in the world of “normies,” there are parts that don’t fit the narrative.) Maybe it’s best so see these as strands of the self-story that truly aren’t compatible with the rest. Maybe they are “clips” (when we actually bother to see them at all), but not self-stories per se. In fact, maybe their incompleteness reflects this. Maybe those strands are “doomed” to remain incomplete.

to get high, being determined, being defiant about getting high. (Even in the world of “normies,” there are parts that don’t fit the narrative.) Maybe it’s best so see these as strands of the self-story that truly aren’t compatible with the rest. Maybe they are “clips” (when we actually bother to see them at all), but not self-stories per se. In fact, maybe their incompleteness reflects this. Maybe those strands are “doomed” to remain incomplete.