A while back I promised to survey the three most common models of addiction – disease, choice, and self-medication – and say something about the advantages and weaknesses of each. I got hung up on the choice model for a few posts: there’s so much there to think about. But now let’s look at self-medication as the essence of addiction.

A while back I promised to survey the three most common models of addiction – disease, choice, and self-medication – and say something about the advantages and weaknesses of each. I got hung up on the choice model for a few posts: there’s so much there to think about. But now let’s look at self-medication as the essence of addiction.

The self-medication model seems to be the kindest of the three. It has the advantage of the disease model, in absolving the addict of excessive blame, but it has the additional advantage of avoiding the stigma of “disease” and all that goes with it. In fact, it gives control (agency) back to the addict, who is, after all, acting as his or her own physician. Whereas the disease model places agency in the hands of others and casts the addict as a passive victim. Furthermore, the self-medication model just might be the most accurate of the three.

The idea is simple: trauma is the root cause. Trauma includes abuse, neglect, medical emergencies, and other familiar categories, but it also includes emotional abuse, and above all loss. Loss of a parent during childhood or adolescence can take many forms, including divorce, being sent away from home (in my case) or the shutting down of one or both parents due to depression or other psychiatric problems. Trauma is often followed by post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which includes partial memory loss, intrusive thoughts, anxiety and panic attacks, avoidance of particular places, people, or contexts, emotional numbing or a sense of deadness, and overwhelming feelings of guilt or shame. But if that’s not bad enough, PTSD is about 80% comorbid with other psychiatric conditions – depression and anxiety disorders being chief among them.

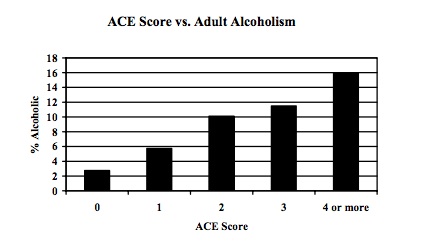

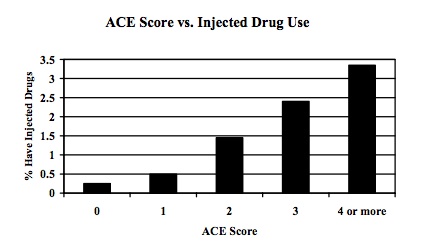

A famous study using a huge sample (17,000) looked at Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in relation to subsequent physical and mental problems. The results of the study are nicely summarized in the Sept. 25/2011 issue of The Fix. Take-home message: the relationship between trauma and addiction is unquestionable. An ACE score was calculated for each participant, based on the number of types of adverse experience they endured during childhood or adolescence. The higher the ACE score, the more likely people were to end up an alcoholic, drug-user, food-addict, or smoker (among other things). Here are two graphic examples:

These figures, which are likely to be low estimates, show a 500% increase in the incidence of adult alcoholism, and a 4,600% increase in the incidence of IV drug use, predicted by early adverse experiences. Wow!!

So how does self-medication work? There must be something about PTSD, depression, and anxiety that gets soothed by drugs, booze, binge-eating, and other addictive hobbies. Again, it’s not complicated. PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders all hinge on an overactive amygdala – one that is not controlled or “re-oriented” by more sophisticated (and realistic) appraisals coming from the prefrontal cortex and ACC. That traumatized amygdala keeps signalling the likelihood of harm, threat, rejection, or disapproval, even when there is nothing in the environment of immediate concern. In fact, this gyrating amygdala lassos the prefrontal cortex, foisting its interpretation on the orbitofrontal cortex (and ventral ACC) rather than the other way around. The whole brain is dominated by limbic imperialism — making it a less-than-optimal neighbourhood in which to reside.

At the very least, drugs, booze, gambling and so forth take you out of yourself. They focus your attention elsewhere. They may rev up your excitement and anticipation of reward (in the case of speed, coke, or gambling) or they may quell anxiety directly by lowering amygdala activation (in the case of downers, opiates, booze, and maybe food). The mechanisms by which this happens are various and complex. But we all know what it feels like. If we find something that relieves the gnawing sense of wrongness, we take it, we do it, and then we do it again.

So, according to the self-medication model, addictive behaviours “medicate” depression, anxiety, and related feelings. But is that the whole story? I don’t think so, and I’ll get into why in my next post.

PS: I have just installed new anti-spam software. If you write a reply that does not appear immediately on the blog site, please let me know!

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

I think this may be my favorite model of all! It’s amazing to me that there isn’t a glut of research looking into this very model, albeit there are some great researchers out there looking into stress and drug addiction comorbidities. To me, it does seem like the most ecologically valid approach. I mean, we have to mildly stress our animals to get most of them to reliably self-administer drugs, but don’t talk about it nearly enough in publications!

If anyone gets the opportunity to see Rajita Sinha speak, I wholeheartedly recommend it!

http://psychiatry.yale.edu/people/rajita_sinha-3.profile

So it seems to me. But here’s what I’m curious about: what do those in the “disease” camp, many of whom are psychiatric researchers, make of the self-medication model? It seems that the disease model places the root cause in the substance itself, and the brain changes that result from it, whereas the self-med model locates the cause in environmental traumas and people’s vulnerabilities to those traumas. But it must be more nuanced than that?!

Agreed. We need to remind ourselves that the most ecologically valid model incorporates a baseline brain state that is conducive to developing compulsive drug use (e.g., a depressed, impulsive, etc… endophenotype) and how drugs alter brain chemistry to achieve some sort of “relief” from anxiety, depression, boredom, etc…

Interestingly, this makes me think that the “disease” model is not necessarily wrong, just incomplete. The “disease” is an entrenched pattern of negative thought formations that lead to distress, loneliness, etc…This likely results from the culmination of life stress and a propensity to develop mental afflictions. I don’t think I stood a chance of escaping my “addiction” to binge-restrict eating. A genetic tendency toward anxiety, a post-partem depressed mother, and bullying during childhood left me searching for something I could focus on to make me feel good, rewarded, and accomplished. However, the eating disorder, like drugs, were not the cause of this underlying brain state.

I wonder how the perception of mental illness as something to hide, and not regard as a serious affliction on the same level as more “physiological” disorders like cancer, diabetes and heart disease, contributed to the characterization of drug addiction as a disease. Perhaps some thought that characterizing it as a mental illness would compromise its acceptance as a serious disorder?

Okay, let’s call the disease model incomplete for now. It either ignores trauma or else shovels it into a bin labeled “vulnerabilities” or “predispositions” along with a few other things. Smoking predisposes one to lung cancer, etc, etc.

Well, that seems partly correct. Trauma-induced depression doesn’t necessarily “cause” addiction, and addiction can certainly arise in lives that are not characterized by trauma. For example, watch that video suggested by Steve Matthews on July 16th: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7thZbHTvZIQ First, he’s right, it will bring tears to your eyes, and second, it brings forth the image of a disease far more readily than trauma-induced self-medication.

But! (but, but, but) I still cringe a bit when you say “The “disease” is an entrenched pattern of negative thought formations that lead to distress, loneliness” Why not call that, say, personality development? Like you, my disposition and environment made it pretty likely that I’d get lost in an addiction some day.

Now as to calling something a mental disease as a way to shove it into a corner…….maybe, maybe not. The notion of a “mental disease” seems a kind of neon billboard: I am seriously fucked up! I may not be contagious, but you don’t want to get too close!

Hi Marc

Thanks for sending this my way. You must be clairvoyant because one month after recovering (one of the “lucky” 15% or so from Mersa) from my previously described illness, my father died under fairly traumatic circumstances. He had a benign tumor growing too near the brain stem for intervention and was the victim (taking me with him at my age) of ever-increasing Grand Mal seizures. Happened in church, public you name it. That was almost worse (for me) than his death.

My mother was a real rock holding the family together with my father dying upstairs and me (possibly) dying downstairs. BUT psychologically and with good intentions she was a PTSD one woman wrecking crew. Told me my father was asking for me but would not let me see him or view the body to say goodbye or whatever. Guilt on steroids.

That is what put so many shrinks on the wrong track about my rec drug use and depression in my twenties. They assumed it was PTSD but it was a COMBINATION of severe childhood brain infection and the death that did it. A double whammy. That was only discovered recently. That is why mine is endogenous and so hard to treat. There are no “magic bullets” for what I have. But with several suicide attempts aside (serious ones) I have never given up. One foot in front of the other, one day at a time, has always been my strategy.

But as you know true alcohol addiction (and I know the difference) did not visit until my 50’s with the exception of cigarrettes, which I quit for 15 years after discovering the youngest had asthma.

BTW my Doc and I were discussing your experience (I made him read your book) and concluded that your drug use seemed more of a compulsion than addiction although those lines can blur. Being a binge user it was unpredictable when the compulsion strikes but it was a different form than classic addiction. You can still use alcohol seemingly without affect. I can use pain killers and forget about taking them. But I have smoking and alcohol as true addictions. And I was a DAILY drinker towards the end. I could not stop after crossing what I call “the invisible line” into true addiction….Stage One (of 3) addiction to alcohol……huge difference between that and what I experienced in my twenties.

BTW #2: I used rec drugs, in part, because the anti-depressants in those days were sledge hammers compared to now. I would rather give up than take a goddam MAO Inhibitor for one example. So in a way those recs saved my life.

Thanks for sending your submission. I already know most of it but I can glean new info from almost ANY study.

Best Rgds

JLK…(my normal signoff once people know me)

Many people see “true addictions” as slipping into compulsive behaviour with respect to a certain substance or activity.. I wouldn’t know where to draw the line. Yes, I can use alcohol within limits, but the compulsivity that characterized my addiction isn’t that different from what I hear from others in describing their own.

As for magic bullets, I don’t know of any that work for any form of addiction. If only there were…

Studying the self-medication model is problematized by endogeneity: it is extremely difficult to assess, particularly in the absence of longitudinal data, the direction of the causal relationship in question. Much of the extant research has suggested that self-medication hypothesis is not a plausible etiology (e.g. Raimo and Shuckit 1998, Muiser, Drake and Wallach, 1998), and that the causal direction and proximity may not be so elusive. More recently, Fergusson, Boden and Horwood used fixed-effects modeling in conjunction with structural equation models to determine the direction of causality for alcohol abuse or dependence (AAD) and major depression (MD) (Fergusson, Boden and Horwood, 2009). Their findings “suggest that the associations between AAD and MD were best explained by a causal model in which problems with alcohol led to increased risk of MD as opposed to a self-medication model in which MD led to increased risk of AAD” (Fergusson et al. 2009).

This is a very relevant perspective, and I have no doubt that it captures a great deal. But doesn’t what you’re saying amount to a feedback loop? In which adverse life events lead to experimenting and then pursuing addictive behaviours, which THEN create their own generous helpings of shame, anxiety, social isolation, depression, and so forth? If we look at self-medication as a spiral relation, a feedback loop, then two things remain to be examined:

1. Where does it start? Is the “initial event” the traumatic experience OR the involvement with addictive behaviours? (Or….do they actually co-emerge? That seems unlikely, unless you trip and break your collar-bone on the way back from the toilet during your first sojourn in the local bar.)

2. If you try to look at causation in a feedback cycle in a linear way (which we are forced to do by nearly all of our statistical procedures — which are based on the “general linear model” — including SEM!), then all you’ll find are artifacts. The only way to track causation in a feedback loop is through very specialized techniques, such as Markov modeling or event-history analysis. Because the cause keeps changing hands, from a to b and b back to a, round and round.

Yes, I think it does (re: feedback loop). The problem lies, as you have suggested, in using regression-based modeling to try to capture something this heterogeneous. I suspect Markov modeling is also going to be problematic as it ‘memoryless’…what we need to work on is an agent-based model of addiction, frankly; something that will capture the complex adaptive features of the behaviour and explain micro-marco interactions.

*macro, even.

Agent-based models would be ideal. But difficult!

Hi Marc,

I recently devoured your book -I’ve never read a book so compulsively, or quickly before. Thank you for writing it, and sharing your journey.

My question following the reading is somewhat related to this recent blog, as I suppose I have got cravings/cumpulsion for what I do.

About 4 years ago I started doing meditation. I learnt the Vipassana technique and I try to do this for an hour each morning and evening. If I miss out on a sit I feel like a piece of the jigsaw puzzle is missing, I guess it’s feeling uncentred or not grounded. I wouldn’t describe myself as then being highly anxious, but I certainly make it a priority to get to that cushion.

I’ve noticed a great improvement with my memory and concentration, as well as the resultant improved relationships with others, and a happiness with myself.

Can you tell me what’s happening in my brain with regard to the biochemicals and pathways?

Is it simply taining these pathways to work ?

Thank you for your work in these matters,

Sincerely,

Nancy Vozoff

Hi Nancy,

There is a growing industry of research related to meditation, mindfulness and so forth. Must be hundreds of studies so far, some using meditation experts who’ve been at it for decades, some using novices before and after a mindfulness training session, etc, etc.

I haven’t looked deeply into this research. From what I do remember, long-term meditators show a good deal more empathy for others’ suffering, and that is partly underpinned by greater activity in the insula, a part of the corticolimbic interface involved in being aware of feelings. Other studies show greater left-frontal activation (Davidson’s group). That’s the half of the prefrontal cortex that is more objective, less driven by emotion. But these are only glimpses by a nonexpert.

It sounds like meditation is a wonderful thing for you. I wish I had the time and discipline to do more myself, as I also find it very fulfilling.

And thanks for your kind words about my book. Always great to hear!

Hi Nancy,

I would recommend reading Dr. Dan Siegel’s book The Mindful Brain! He strikes a very nice balance between subjective, experiential aspects of vipassana meditation and the correlations in brain structure/function that occur. He also offers a healthy dose of speculation about the possible mechanisms of change.

Also, Dr. Lewis mentioned Richard Davidson’s research – he has a new book out titled The Emotional Life of Your Brain. I have yet to read this one myself but he’s probably the best-known researcher of meditative states of mind.

Hi Jordan.. Haven’t read the recent Siegel book yet, though I liked his first book a lot.

Yes, Davidson is very well known. I should mention another study first-authored by a member of his group…Antoine Lutz. In this study, experienced meditators and control participants were asked to look at a “random-dot stereogram” — a sort of hodge-podge of colours and shapes — until it converged into a recognizable image. This is a well-known optical trick. Anyway, at the moment of convergence, the brains of the meditators showed far more CONNECTIVITY among regions of the prefrontal cortex than did those of the controls. Neuronal connectivity is the best metric we have for how well and how comprehensively the brain is communicating with itself!

That study is part of a research program called “neurophenomenology” — really interesting stuff (inspired by the work of Francisco Varela). Here’s a link to a review chapter: http://espra.risc.cnrs.fr/LutzThompson.pdf

Oh, and here’s a link to that empathy/insula study: http://www.news.wisc.edu/14944/

I’m not sure what the ‘self medication position’ says, exactly.

Seemingly it’s more than 1) Childhood abuse/neglect/trauma

cause psychological disorders, up the road. Does it say that

2) compulsions and addictions are attempts (however ineffectual)

to deal with the symptoms (e.g. anxiety) of these problems?

I suppose that all neurotic or seff hindering or self destroying

patterns are attempts to cope with life’s miseries, with the usual

addition that a) they don’t work that well, objectively, but b) the

person is somehow attached to or stuck in them and *believes*

he or she is doing well–or as well as possible– in the chosen

path. That’s true in my experience, but I don’t know if my

patterns, as desperate attempts to deal with stuff, represent

‘self medication.’

Lastly, I don’t think the Kaiser study showed good evidence for 1),

but rather, possibly, for the position that lots of people believe 1).

Certainly this approach pays a lot of attention to the amazing prevalence of childhood trauma, and it’s interested in the spreading influence of trauma into a number of different psychiatric effects. Now whether self-medication is merely one effort among many to make oneself feel better, and whether it really works or one just believes that it works or that it’s the best option going, remains to be examined.

It’s true that the Kaiser study (the ACE study) doesn’t tackle this kind of question. It seems to show causal relations, though Conor’s comment (above) throws some doubt on this. At the very least it shows powerful correlations, and in my view that’s a good start.

What I find most puzzling about the self medication position is this (I contrast the position with the commonplace that ‘neurosis’ and character disorder [and substance abuse] are attempts to deal [cope] with life’s misery, which often do not work very well, or even increase that misery, but are persisted in, nonetheless):

What counts as ‘medication?’ If I get depressed and make a series of suicide attempts, does that count as ‘medication’? If I go and find my childhood abuser and try, continuously, to make his life miserable?

So, medication doesn’t always work. And sometimes it’s harmful. A treatment that makes matters worse rather than better is called “iatrogenic”. There was a recent meta-analysis of SSRIs (the most commonly prescribed drugs in the US) that showed that THEY DON’T WORK…except in cases of severe depression. So their effects in other cases must be placebo effects. I was kind of shocked by this, and I embarrassed myself in a debate by insisting that it must be wrong. Anyway, the point is that psychiatric cures are perhaps the most suspect of any. They often don’t work, and they are notorious for making things worse. (Think of people with psychotic problems reduced to zombies by major tranquilizers!)

PS. I suppose suicide would be the epitome of a treatment with iatrogenic effects. Although….well, it does solve the problem in one sense.

Hi Marc

Hope you enjoyed your holiday? I really like the self medication model but don’t really see it conflicting that much with the dis-ease model. Pretty similar, if not exactly the same as Bruce Alexander’s findings in rat park and the globalisation of addiction. Substances, and addictive behaviors are things we do to cope with the feelings we get from the environments we find ourselves in. Bruce talks about dislocation as being one of the the primary factors of addiction and, in much of the work I am currently involved with, I am dealing with indigenous people dislocated from their cultural backgrounds trying to medicate the traumatic feelings they are experiencing.

Large sections of society have been disenfranchised and, quite often, ghettoised. They have lost their cultural and spiritual boundaries and have very little hope or aspiration. They grow up with almost constant sense of disappointment, fear and social alienation and use substances and/or behaviors to medicate and, hopefully, become part of something.

We are experiencing quite a strange phenomena, here in the UK, as austerity bites high street shops close because people have less and less to spend. However, despite this, betting shops, where people can gamble in all sorts of ways, are popping up everywhere. It seems that as a greengrocer or butcher shop closes another betting shop opens. Some high streets, containing around 100 shops have at least 15-20 betting shops! Is gambling the new Heroin? I ask myself!

Rat Park: a study that showed that a boring, isolated, and impoverished environment leads to self-administration of morphine in lab rats, whereas rats housed in a rich, diverse, social environment preferred water to morphine solution. A beautiful demonstration of self-medication if ever there was one.

One of the chapters in my book is entitled “Night Life in Rat Park” in honour of that study. I was running rats late at night in the sub-basement of the psychology building, while doing my stint as a post-BA makeup psych major. In retrospect, I was like one of Alexander’s impoverished rats. My social life was close to zero, and the creature comfort I relied on all came from my recent marriage, which was already on the rocks after only a few months. I was a living, writhing, paragon of psychological trauma. I felt trapped in an unhappy marriage, depressed, lonely, and ashamed. And the word “dislocation” applies perfectly — my life was a constant tug-of-war between a fractious marriage and a seemingly endless line of rats waiting for me on the night shift. I didn’t know who I was or where I belonged.

And then, you see, Officer, there were all these bottles of morphine in the fridge, left over from previous experiments. So like Alexander’s unlucky rats (those who weren’t invited to live in Rat Park), I went for the morphine — screw the water. (There’s an excerpt from this chapter in a previous post: https://www.memoirsofanaddictedbrain.com/connect/countdown-in-the-rat-lab/)

It’s great that you are taking the idea of dislocation and applying it to the addiction problems of indigenous groups who have lost their cultural heritage, as well as others who are disenfranchised, buffeted by life more than living it. That seems a very apt perspective on the tendency for natives in N. America, as well as poor, ghettoized non-whites in much of the Western world, to become addicted, whether to booze, solvents, or low-grade heroin. (The poverty of these groups leads to dependence on the most harmful substances imaginable.)

And gambling! It’s become such a big problem for North American natives that their own land (the “reservations”) has become pock-marked with casinos. Not surprisingly, the culturally impoverished rats are also those who become financially impoverished — if they’re not already broke.

Hi marc

In answer to Conor: I really don’t have a lot of faith in “studies” as they always seem to have missing components and are normally not conducted by “real addicts” who can truly empathise with the condition. (That may be my AA training talking there… if so apologies)

When you become an addict it is (or should be although many remain in denial) internally obvious. It is often described as a compulsion, disease whatever. But I can tell you this that in my experience drug use was a survival technique to “get me off the planet” when the pain of depression became unbearable.

After witnessing the life stories of addicts in hundreds of AA meetings I can say with certainty that the majority “inherited” the disorder whether the mechanism be nature or nurture. (I believe nature or inherited genetic tendency personally) Which goes on to show that in my case, with no addiction in the family, it (alcoholism) was somehow triggered by long term use/abuse. Of course my case is also complicated by the juxtaposition of trauma and brain infection from the Mersa.

To Nancy: Keep it up! Virpassna is highly effective for many people. You might seek out other practitioners as well like I did. It was a big help in refining the techniques.

Rgds

JLK

Yes, it seems that the predisposition (vulnerability) to addiction can derive from nature or nurture — but most likely their interaction. A person with a genetically-hard-wired sensitivity to loss (and you can see this in babies who scream their heads off when Mom puts them down to take a phone call) will be “traumatized” by parental divorce or parental absence, whereas those who are less likely to rely on social attachments might come through those situations unscathed.

But I wonder if it really does become “internally obvious” when one crosses the line to become an “addict”. You mention denial. That’s a critical defense mechanism for many of us. Coupled with the comforting effects of drugs or booze as self-medication, denial might be highly recommended by the same internal physician. In other words, it might be less stressful to remain unaware of how bad things have gotten — until they’ve gotten even worse.

But I wouldn’t want addicts to be conducting the research on addiction. Beside the likelihood of certain lab supplies disappearing with great regularity, I’m still stodgy scientist enough to want large helpings of objectivity (or a close approximation) in my diet. And then pop science writers (like me I suppose) can put the subjective stories and the “objective” facts and figures together — creating a new product, a hybrid, that’s much more persuasive than either ingredient alone.

Hi Marc

I believe you and Nik, as researchers, are a bit too dismissive of the individual experience. Ex: (part repeat) my latest vascular travail was an 80% clog in my right caorotid. My theory, that I gave the first vascular surgeon, was that the lack of blood flow to the neuro modulating centers that control the emotions that cause me problems (dopamine,serotonin,norepinephrine etc.), was causing these horrible (and potentially deadly) mood swings, almost Bipolar in nature except all pointing down, not up.

The 1st surgeon dismissed it without even considering,(I’ve seen his notes). The 2nd took me seriously enough to order a CAT scan that showed something even more deadly. So I was rushed into surgery.

Turns out after 3 months (post surgery) my theory was 100% correct and OHSU is now considering a study. So what I am saying is a dismissive attitude on the part of physicians because there have been no “studies” can be deadly.

Marc: I did not say everyone felt this “invisible line”.. I did…and (I believe)you are a little dismissive of the mersa affect on my brain mainly because of the juxtaposition between that and a traumatic experience. Well, having major childhood infections IS a cause of whacked out pathways that my brain specialist says move on a continuum from what I have (“Double D” as I call it), all the way to full blown OCD. He says “I am lucky”…. hard to accept considering what I have been through. But OCD would be the most painful of all disorders…… in my experience/opinion.

Rgds

JLK

Hi Marc. I just sent a post that hasn’t immediately appeared on your site. -Jasmine

Thanks for telling me, Jasmine. I’ll look into it right away.

Did you copy and paste the number in the box? That’s the thing you have to do now to post your comments.

Hi Marc,

I’m wondering what your thoughts are on trauma experienced pre birth due to the mother experiencing trauma. I’ve heard this can cause a problem with brain development and the ability to cope with emotions. Is this true?

Thanks

Jo

Hi Jo. I’m rusty on this research. But I recall that LARGE quantities of stress hormones like cortisol can damage parts of the brain. Mother and fetus share the same blood of course, so whatever is circulating in Mom’s system is also circulating through the baby’s body while it’s developing. For more info, here’s one recent review: http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2008/02/03/anxiety-for-two.html

Still, I wouldn’t get too stressed out about stress. Anecdotally, we constantly hear of moms in the worst imaginable situations (including impregnation via rape) who have very healthy babies. I’d say that the greatest threat to the developing infant is the mother’s mood (e.g., depression, anxiety), which will partly determine her sensitivity to infant signals, as well as her emotional availability, in the months following birth. Mom’s levels of depression and anxiety will, in turn, depend on stressors before, during and after giving birth, and critically on the kind and amount of support she gets from others.

Oh, and naturally stressed-out pregnant women are more likely to drink, smoke, or do drugs, all of which can have effects on fetal development. But even this is not a simple story — a glass or two of wine might be better for mom and fetus alike, compared to a boozeless state of relentless anxiety.

In my opinion, the retrospective issue is the key problem in the ACE study (based on Kaiser contacts). The best method would be to collect info about life’s events (or access the person’s files compiled by others, at the time of the events, e.g. at children’s aid societies)as they happen, and also–as life unfolds– info about psychological and other life probs.

Asking people after the fact, _people who have become convinced that their childhood abuse caused their problems_**,simply gets accounts from them that confirm their theories (which one here, shares).

At very least, the Kaiser people should have asked “how convinced are you that your childhood trauma caused your problems?”, to see if the most convinced gave accounts that more highlighted the correlation. And conversely.

**Why do I think this sample, however large, was mostly convinced as to the effects of childhood trauma, abuse and neglect? I think it’s in our culture, e.g. with the Oprah show. Further at any number of 12-Step meetings you hear persons who’ve had contacts with counsellors and therapists; such person say, for example, “My father mistreated/neglected me. or “My mother was an alcoholic.” I don’t mean they

are making excuses, but they have a theory. And I’m not saying it’s wrong; that the events cited have no influence.

What I’m saying is that if you ask such a person questions as in the ACE study about childhood (adverse) incidents and his or her present situation, the answers can’t helpYOU, an objective investigator, confirm hypotheses about influences of childhood events. Your evidence is tainted.

Excellent points, Nik. These sorts of reporting biases are always potential sources of bad data in psychological/health research. The possible outcome, as you say, is “tainted data” which is arguably worse than no data at all.

Here’s a link — http://www.cdc.gov/ace/about.htm — to a CDC page summarizing aspects of the Kaiser study and providing useful links to more detailed reports as well as related research.

The bad news is, as you say, the worst sort of confound of a retrospective study. Questions about family functioning, abuse, and neglect, were asked by a mailed-out questionnaire which ALSO INCLUDED questions about current (physical and mental) health status. Indeed, even if participants were “blind” to the hypotheses, it wouldn’t be surprising if many of them tended to exaggerate the prevalence of past adverse experiences if they were also currently having health problems (or vice versa: exaggerating present woes in combination with past adverse events), because they inferred what must be of interest to the researchers. This sort of bias is almost always unconscious and therefore very difficult to track.

The good news is that a “prospective” phase (the opposite of retrospective: measuring things when they happen and then waiting to follow up on whatever happens next) is already underway, and replication studies are popping up all over the world. (see the above link)

Thanks for your critical eye.

Hi Marc,

I’m reposting my original comments which didn’t process properly the first time……

I’m not a scientific person and my exploration into learning about addiction has been through my own experiences, others’ accounts of their experiences and reading psychological material, sort of in the Gabor Mate sphere. However, I’m interested in a possible genetic link to substance abuse, what could be termed a pre-disposition or even a ‘dis-ease’. It’s been established that many methamphetamine users (I’m not one, by the way) gravitate to this particular habit if they suffer from ADHD, Apparently, it helps them focus and think more clearly, much like the prescribed drug Ritalin does, but without some of the unpleasant side effects of Ritalin (although, Meth takes it’s toll in a much worse way, eventually).

Personally, I’ve struggled with food and nicotine. I also have a history of anxiety disorder which bloomed into agoraphobia when I hit the age of 14 and I’ve struggled with it to greater and lesser degrees for most of my adult life. About four years ago, I was prescribed a combination of anti-depressants (SSRI’s) which made an enormous difference in my life in terms of curbing the free-floating anxiety that had dogged me for years, enabling me to finally function normally. So, I started thinking about the possible genetic implications of this. If my brain has a naturally low level of serotonin or dopamine or whatever, then in order to self-soothe my anxiety if I’m not getting the brain chemicals I need (before the anti-depressants came into the picture), I would gravitate toward feel-good carbs and nicotine. (Nicotine has a duel function, acts as both a stimulant and a relaxant). The other thing is, from the moment I was born, I sucked two fingers on my left hand, until about age 7 when my mother ‘cured’ me of the habit by making me wear cotton gloves for a period of time. So this self-soothing gesture was a constant for me when I was a child. In terms of my family history, my father’s side has a high rate of anxiety and phobias (aunts and uncles) and my mother went through a period of social phobia as an adult. Sometimes people will gravitate toward certain substances like alcohol to mask anxiety disorders, particularly men, who have more difficulty asking for medical/psychiatric help. So, if anxiety disorder is a disease (studies have been done such as injecting lactic acid into test subjects and in a percentage of them this induced panic attacks, but not in others), maybe due to a brain dopamine deficit or whatever, then maybe some addictions are born out of the brain’s need to compensate fo the chemicals that should naturally be there?

.

I’m glad your comment finally made it through. A few posts ago, I reviewed some research showing correlations between personality traits and experimentation with drugs or drink in adolescence (https://www.memoirsofanaddictedbrain.com/connect/a-genetic-blueprint-for-addiction/). Some of these effects were related to specifiable differences in brain function (cortical inhibitory networks), but the picture was rather complex and some expected correlations were nowhere to be found. Also, the one characteristic most likely to predict experimentation was — you guessed it — impulsivity. Which really just means that impulsive adolescents are more likely to try things of a fringy nature.

This kind of finding led me to downplay associations between prespecified brain differences and addiction outcomes. But that said, your hypothesis still makes a lot of sense. People have different sized noses, different colours and amounts of hair, differently tuned systems from breathing to bowels… So why should there not be intrinsically different levels of key neurochemicals? In which case, taking certain drugs would be an obvious way to bring your levels — of whatever — closer to the norm. And….that should count as a very sensible form of self-medication.

So I accept what you say about differences in key neurochemicals. What I question is how those differences came about. People with ADHD may indeed be drawn to meth because they have less frontal dopamine or their dopamine receptors aren’t as efficient as they might be. There’s research in support of such differences. And yet no gene or package of genes for ADHD has been confirmed (despite many valiant efforts) and twin studies show low or nonexistent correlations among close family members.

My (unsupported) opinion is that differences in the neurochemistry of self-soothing (opioids), selective attention (dopamine), and so forth, DEVELOP with experience. I tried very hard, against rather high odds, to soothe myself when sent away to boarding school. So, functionally, my opioid metabolism wasn’t up to the task. Functionally, I was starved for opioids. And maybe that produced physical differences in opioid production or reception, or maybe it produced thought patterns and feeling patterns (e.g., subserved by an overactive amygdala that had to be constantly soothed) requiring high-octane opioids just to stay sane. So….I eventually became an opiate addict. Self-medication indeed.

In a nutshell, I’m with you in seeing drug-taking as self-medication for insufficiencies (or excessive levels) of key neurochemicals. But I’m not so sure these differences are built in. So when you say you may have had “a naturally low level of serotonin or dopamine or whatever”….I wonder how “natural” that really was. It could still be the product of experience, of family dynamics, of trauma — and these psychological effects could be the common link you note with other members of your family.

I’ll just end this long disquisition by saying….it may not matter much one way or another. Whether deficits in key neuromodulators were present at birth, or whether they developed through stressful interactions, let’s say, with parents, perhaps in infancy, you’re still stuck with them. And either way, drugs (prescribed or otherwise) might be a handy dandy way (did I really say that?) to top up the levels so that you feel better and function better.

Wow, thank you for the article. I am not a scientist. I am a clean and sober drug addict. I do not know which of the model is ‘correct’ but I feel like aspects of each apply to me when I examine my history. I think self medication most accurately describes my experience. This was a very interesting article to read…thank you for posting. I got clean and sober with the help of a sober living called New Life House. Check out their site anyone who is looking for help. http://www.newlifehouse.com

Thanks, Eddie. I’m glad it makes sense. And I’m glad you’ve posted the website of your recovery program here for others in need.