Just finished day 1 at the Mind and Life conference. What a beautiful building this is for a conference. The corridors seem to echo with the shuffling feet of Christian monks. But now, in our modern age, there are a lot of shaven-headed guys with orange robes walking around. It’s strange to see them in the washroom with everyone else, shaving, brushing their teeth. Very corporeal. But most people here are young scientist types, assistant profs or post-docs in psychology or neuroscience, but incredibly friendly and warm-hearted. And a few old guys, like me, except that they look like they’ve known each other for decades. It’s weird to meet a guy with a name like Saul Weinstein who turns out to be an expert on meditation.

Just finished day 1 at the Mind and Life conference. What a beautiful building this is for a conference. The corridors seem to echo with the shuffling feet of Christian monks. But now, in our modern age, there are a lot of shaven-headed guys with orange robes walking around. It’s strange to see them in the washroom with everyone else, shaving, brushing their teeth. Very corporeal. But most people here are young scientist types, assistant profs or post-docs in psychology or neuroscience, but incredibly friendly and warm-hearted. And a few old guys, like me, except that they look like they’ve known each other for decades. It’s weird to meet a guy with a name like Saul Weinstein who turns out to be an expert on meditation.

Today the talks were on heady Buddhist topics, loaded with Sanskrit and Tibetan words for different traditions. I had to struggle to focus. I’m still a bit jet-lagged and my mind is buzzing with worldly things. In fact today’s meditation session was a total write-off. Tomorrow’s talks will be on neuroscience. That should wake me up.

Today the talks were on heady Buddhist topics, loaded with Sanskrit and Tibetan words for different traditions. I had to struggle to focus. I’m still a bit jet-lagged and my mind is buzzing with worldly things. In fact today’s meditation session was a total write-off. Tomorrow’s talks will be on neuroscience. That should wake me up.

What’s most strange about this event is that I’m staying in a small room with another guy. Two beds side by side, and four tiny shelves for our stuff. I haven’t shared a room with a stranger since boarding school. He’s a prof in religious studies at a university in Pennsylvania. A nice guy, actually. Still, he’s very close.

Anyway, not much more to say for now, so what I’ll do is post the second half of an article I just wrote for the Mind & Life newsletter.

To prepare for the meeting [with the Dalai Lama], I’ve been trying to think like a Buddhist for the last few months. And what strikes me most is that the Buddhist perspective on personal suffering, based as it is on desire and attachment, captures addiction surprisingly well. So well, in fact, that addiction comes off looking like a fundamental aspect of the human condition.

To prepare for the meeting [with the Dalai Lama], I’ve been trying to think like a Buddhist for the last few months. And what strikes me most is that the Buddhist perspective on personal suffering, based as it is on desire and attachment, captures addiction surprisingly well. So well, in fact, that addiction comes off looking like a fundamental aspect of the human condition.

Buddhism sees attachment, craving, and loss as a cycle — a self-perpetuating cycle — in which we chase our own tails and lose sight of everything else. What Buddhists describe as the lynchpin of human suffering, the one thing that keeps us mired in our attachments, is exactly what keeps addicts addicted. The culprit is craving and its relentless progression to grasping. First comes emptiness or loss, then we see something attractive outside ourselves, something that promises to fill that loss, and we crave it. And the next thing we do is grasp — reach for it. Grasping leads to getting: a brief moment of pleasure or relief that reinforces the attachment. But it’s never enough, we crave more, and that’s what keeps the wheel going round. Whether the goal is success, material comfort, prestige — the more respectable human pursuits — or whether it’s heroin, cocaine, booze, or porn, hardly seems to matter. Either way, you’ve locked your sites on an antidote to uncertainty, a guarantee of completeness, when in fact we never become complete by chasing after what we don’t have. And, incredibly, the pursuit itself is the condition for more suffering. Because we inevitably come up empty, disappointed, and betrayed by our own desires.

Now that sounds a lot like addiction to me. Yet the Buddhists are talking about normal seeking and suffering. Isn’t addiction something abnormal? What about all those brain changes I mentioned? [which took up the first half of the paper.] Those brain changes suggest to most scientists and practitioners that addiction is a disease — an unnatural state. But a Buddhist perspective might cast it quite differently, as a particularly onerous outcome of a very normal process, a sadly normal process: our sometimes desperate attempts to seek fulfillment outside ourselves.

So what about those brain changes?

It turns out that the brain is designed to change. Every advance in child and adolescent development requires the brain to change. The condensation of value and meaning in adolescence corresponds with the loss of about 30% of the synapses in some regions of the cortex. As with addiction, normal development involves a lasting commitment to a small set of goals: I’m going to make money, I’m going to live in a secure neighborhood, I’m going to find a life partner. And that involves the formation and consolidation of new neural networks at the expense of older ones. In fact, every episode of learning, whether to play a violin, move in a wheelchair, or see with your fingers after going blind, requires the growth of new synaptic networks. Such cortical changes ride on waves of dopamine, in normal development as in addiction. Gouts of dopamine, with its potency to narrow attention and grow synapses, are highly familiar to lovers and learners alike. That palpable lurch for sex, admiration, or knowledge is always dopamine driven. The brains of starving animals are transformed by dopamine, when, as in addiction, there’s just one goal worth pursuing. And successful politicians achieve dopamine levels that would make an addict swoon. The brain evolved to connect desire and acquisition, wanting and getting, and that connection depends on the tuning of synaptic networks to a narrow range of goals with the help of dopamine.

For both normal development and addiction, desire acts as a carving tool, collapsing neural flexbility in favor of fixed goals. So our understanding of addiction may benefit more from a Buddhist-style perspective on normal development — with its tendency to become fixated on attractive goals — than the disease model favored by Western scientists and doctors. Yet the Buddhist perspective offers another advantage: an emphasis on the value of mindfulness and self-control to free ourselves from unnecessary attachments.

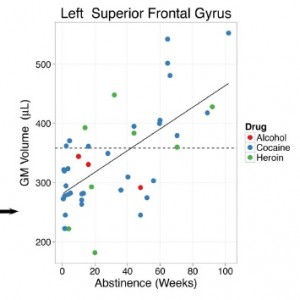

On that note, I’ll end by touching on a provocative experiment recently published in PLOS1, a prominent scientific journal [and brought to my attention by Shaun Shelly on this blog]. It’s well known that cocaine addiction causes reduced grey matter (GM) volume — thought to represent a loss of synapses — in certain regions of the cortex. But these  researchers found increasing synaptic thickness in cocaine addicts who had abstained for several months: and the longer the period of abstention, the greater the growth. Most striking of all, the new growth wasn’t simply a reversal of what was lost, like a pruned bush growing back its leaves. Rather, synaptic growth was observed in new areas — areas known to underlie reflectivity and self-control. In fact, this growth surpassed levels reached by “normal” (never-addicted) people after a period of 8-9 months, indicating the emergence of more advanced mental skills. If these results are replicated, they’ll provide solid evidence that recovery, like addiction, is a developmental process, which may benefit from the advanced cognitive capacities facilitated by mindfulness training.

researchers found increasing synaptic thickness in cocaine addicts who had abstained for several months: and the longer the period of abstention, the greater the growth. Most striking of all, the new growth wasn’t simply a reversal of what was lost, like a pruned bush growing back its leaves. Rather, synaptic growth was observed in new areas — areas known to underlie reflectivity and self-control. In fact, this growth surpassed levels reached by “normal” (never-addicted) people after a period of 8-9 months, indicating the emergence of more advanced mental skills. If these results are replicated, they’ll provide solid evidence that recovery, like addiction, is a developmental process, which may benefit from the advanced cognitive capacities facilitated by mindfulness training.

Based on studies such as these, and filling in the blanks with subjective accounts, addicts, scientists, and contemplatives have a lot to learn from each other. I hope that this theme will help guide the discussion with the Dalai Lama in October. Ater all, addicts and meditators make use of the same brain, with all its vulnerabilities and strengths. It makes sense that the brain changes underlying suffering and healing have much in common, whatever their source.

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Informed by unparalleled neuroscientific insight and written with his usual flare, Marc Lewis’s The Biology of Desire effectively refutes the medical view of addiction as a brain disease. A bracing and informative corrective to the muddle that now characterizes public and professional discourse on this topic.” —Gabor Maté, M.D., author of In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction

Increasing synaptic thickness… Wow! I new I was getting smarter then I ever was…hahaha… Great post Marc, I just love this one. It really puts in perspective everyone’s desires, to fill that hole within ourselves by some outside influence. The power of attraction to something other then ourselves. I think we are all addicted to one thing or another. Today for me… it’s ice-cream and thirst for knowledge. Have a great time and I look forward to your next post.

P.S maybe this is how we lost our tails? It wasn’t evolution after all…hahaha…

Regards Richard

Or maybe this cortical thickening is exactly what evolution provided for us….to use or abuse as we see fit!

“Most striking of all, the new growth wasn’t simply a reversal of what was lost, like a pruned bush growing back its leaves. Rather, synaptic growth was observed in new areas — areas known to underlie reflectivity and self-control. In fact, this growth surpassed levels reached by “normal” (never-addicted) people after a period of roughly six months, indicating the emergence of more advanced mental skills.”

YES!

This gives SO much hope to those of us that struggle. While we may have to hit rock bottom, coming out of the addiction process can also bestow upon us a number of lifelong skills in self-control that can translate into a better life, even compared to BEFORE the addiction developed :).

Exactly so. And there may be an emerging consensus, among members of this blog community, that we (addicts, recovering, and ex) have something special. We may have suffered more than most, but we come out burnished, in some way more beautiful than we started.

In the movie ‘The Talented Mr Ripley’ the main character who has assumed the identity of a jet-setter says: “It’s better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody.” That sums up for me that frantic desire-driven ego self whose motto is ‘Me, mine, more.’ It’s the image of the kid with his nose pressed to the toy store window, outside looking in, not fitting in, not comfortable in his own skin, craving fulfillment in escape. And of course there’s never enough toys, food, drugs, sex, money, applause. The desire becomes craving, the craving compulsive, and the compulsion an end in and of itself. The circuit is now closed and autonomous. Happily, as Leonard Cohen says, ‘There’s a crack in everything; that’s how the light gets in.’

I love that Leonard Cohen line! It gives me goose bumps every time. So today I heard a seriously advanced being with a big smile and the title Rimpoche (I can’t pronounce his other name) talk about how to deal with impulses. He said: you don’t have to suddenly grab a hold of the impulse and surround it with your ego. You don’t have to say: that’s me — that’s who I am. You can keep your ego at a bit of a distance, accept the impulse as a part of you, and let there remain some space between your ego (sense of self) and the impulse. Let there be some space there… And that allows the impulse to change.

That’s the crack! That’s how the light gets in.

That sounds right. But there’s a difference between impulse and compulsion. There’s some pull toward payoff in impulse, whereas compulsion is all push, much more tightly wrapped. One reason we aren’t better at helping those with addiction is that we don’t know how to facilitate the cracking open. As the Buddhists say, ‘the blind don’t need light, they need eyes.’ Once there’s that crack, then recovery can be progressive.

I’ve been reading the cult deprogrammers looking for clues, and they’re not very helpful. The addiction field too has tried the boot camp, holding people against their will approach without a lot of success. Compulsions are like ‘true’ beliefs, emotional and not rational: and to challenge them (shine the light) provokes a SNS response of flight or fight.

The initial experiments with kindling exhibited state-dependent-learning. Once the kindled seizures were extinguished, the tiny electrical impulse only reinstated them in the acquisition site.

How do we encourage/promote/facilitate/initiate openness? The ‘stages of change’ research is least helpful with the precontemplative stage. Precontemplative is from a more primitive part of the brain (SNS) and engagement, or re engagement, of the higher brain centers provides the eyes to see the light.

The ‘crack’ needs to come from the inside out. Think of all the addicts who began their recovery with a moment of clarity, or awakening, or begged someone or something for help, or who had that gift of desperation, or who finally ‘got it.’

These are really important distinctions. And indeed the compulsive phase makes it much more difficult for any softening or cracking to occur. And yes, there is a process in addiction very much like kindling — probably exactly like kindling — but involving the extended amygdala including striatum, not just the amygdala. (I’m referring to the kindling/depression story, not the initial rat research)

Nevertheless, Rimpoche was not making a distinction between impulses and compulsions. He was talking about a very real fear of heights he’s had since childhood, and how he finally got himself to walk across a high bridge. Fears of this sort are probably closer to compulsions, as they involve simple stimulus-response conditioning.

Anyway, compulsions are also normally fixated or entrenched in “ego” — this is MY need, this is what I have to do. So I think the same logic can apply: a lessening of the “wrapping” of that impulse or compulsion in a total identification with the self. Yes, there goes my alarm: I feel that I must do x. That is a feeling, and it’s part of me, but it isn’t all of me. So the crack gets room to appear.

Marc, I absolutely adore your high level of intelligence mixed with refreshing down to earthiness 😉

Marc, this is some really powerful stuff. I think/hope that you will be considered in retrospect to be in the forefront of identifying the truth about addiction. I think, in my humble opinion, that a discussion of what separates the addict from the ‘normal’ person is warranted. I take it so for granted that what addicts go through is part of the human condition, yet I know how “revolutionary” your point of view will be considered, i.e., that addiction is not a disease but rather a normal part of living that got a little out of control? that is normal behavior to a greater extent? Is it that the addict initially suffers more or doesn’t know how to deal with suffering? Whatever the answer here, you’ve become part of the discussion and that is tremendous! And, as always, thank you for sharing 🙂

Thank you, Denise. I think/hope that this upcoming meeting will be all about bringing addiction down to earth. The more we find out about brain processes, the less addiction looks like some anomaly. In fact I read a recent paper by Nora Volkow in which she didn’t use the word “disease” once. Mind you, it was a short paper. But I think there may be a consensus on its way.

What an exciting opportunity you have, to contribute, both your knowledge and direct experience. Congratulations.

Yes, I think Buddhism has much to offer; but I also have reservations:

First, you say: //What Buddhists describe as the lynchpin of human suffering, the one thing that keeps us mired in our attachments, is exactly what keeps addicts addicted. The culprit is craving and its relentless progression to grasping.//

So you have a number of ‘cravings’, for beer, for the company of your wife, of your kids. You *had* a craving for opioids and for misc. other drugs. Don’t the Buddhists say, ALL cravings lead to suffering? Would equanimity in the face of loss be the goal? I’ve heard the English term, “extirpate,” used, for cravings. After all, families are wiped out every day in earthquakes, tsunamis.

It seems like the issue of **which** craving is it *very* important to eliminate (or greatly moderate) in order to flourish as a human is not answered. You speak later of “unnecessary attachments”; are the kids necessary? The questions of flourishing as a human seems to be evaded (what the psychologist call, ‘health’).

As you seem to suggest, shouldn’t we ask of the Buddhists, *which* desiring/craving brain states are we trying to move past. Which are truly unhealthy and self destructive, versus simply deluded, non-extreme human striving for worldly goals like fame and money?.

I agree that alternatives to a ‘disease’ perspective are needed, and so Buddhist approaches seem valuable. but….

Lastly, you say, //an emphasis on the value of mindfulness and self-control to free ourselves from unnecessary attachments.//

Mindfulness, certainly. In western terms, that means allowing oneself to feel something (loneliness) without precipitating acting, esp. where these acts, past the first few minutes cause lots of harm to oneself and others. I’m no expert, here, but don’t Buddhists say the self is unreal; as illusory as the visions we have of the craved objects. Hence, in my opinion “self control” as a goal would be in the same category as ‘attainment of desire.’

Do we need to talk about different versions or methods of self control?

My thought, here, for what it’s worth, is that Buddhism *might* help one past some of the dichotomies, such as ‘My Addict” vs. “Myself.” or “My addict” vs. “My Higher Power.”

Does one control the other? Can one control the other? I can picture a Buddhist analysis that undermines the foundation of such talk as “I knew it was My Addict talking; so I called on my Higher Power (or Higher Self) to take care of me.” Does the ‘control’ of addiction involve something beyond ‘control’ in the ordinary sense?

In any case, you have lots to offer, and I wish you bon voyage.

Hi NN. You are painting Buddhism in a very harsh light. Your take on it is so extreme — almost a caricature. As noted in my comment to Nicolas above, and other comments, these guys are very human. They know damn well that they have selves and desires and they always will. They also shit and brush their teeth. Although the ancient texts talk about enlightenment and all kinds of other hypothetical states, it seems the goal of the Buddhists around here is not to eliminate the self but to free it as much as possible from the things that bog it down. In a word, to just be lighter and happier. Ok, two words.

Anyone can go in and make a laundry list of which attachments are useful and which are not. But the point is: much suffering really is caused by attachments, so it would be nice to at least have some choice in how to deal with them, rather than to be mechanically drawn through the ringer each and every time.

I was asking someone about how the Dalai Lama might react to this or that point, when I give my spiel. She said: Well, it may seem strange, but HH doesn’t have much patience for philosophy. If you philosophize too much, he’ll ask you what’s the point? What good is it?

I rest my case.

When asked how to help seekers with addictions, my guru merely told them to meditate, advising the addiction would drop on it’s own.

I can imagine that’s possible. But a treatment guy here says that hard-core addicts have a very hard time meditating….they need some hand-holding first, during, and maybe after. Seems like a combination is warranted.

I am a treatment guy also – 38 years experience. I find the MOTIVATED hard core guys willing to try ANYTHING. The unmotivated are difficult to treat with any therapy!

Marc, you may remember me describing the “toy” experiment of asking my guys in early recovery to sit still, eyes open, in silence, and we could only manage to do this for a few seconds. Well, those same guys are going for an hour this Friday! And those that are still in this group are doing well in their recovery.

Shaun: Congratulations – working with a group that is motivated for change is very rewarding. At present mindfulness/meditation is used as a treatment adjunct. I have suggested moving mindfulness/meditation into a primary treatment technology.

The Buddhist Recovery Network cites 500 studies using meditation for addiction recovery. TM (Transcendental Meditation – mantra repetition) is the most heavily researched technique. Alan Marlat’s Mindfulness Based Relapse Prevention, a combination of mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy was shown to be more effective in the first three months of recovery. Addiction recovery outcome research does not find any treatment method superior to any other treatment method. Treatment technology cannot as yet determine which method to use for each individual (treatment matching).

With over 100 meditation techniques available we should be able to find one for each person:

http://www.meditationiseasy.com/mCorner/techniques/Vigyan_bhairav_tantra.htm

I am as much opposed to the ONE WAY meditation approach as I am opposed to the 12 STEP only approach.

The addict is attempting to alter his reality with chemicals. I have found getting high on meditation is legal and inexpensive (as in the song, I’VE WANT A NEW DRUG – Huey Lewis).

Namaste

Guy C. Lamunyon MSN, RN, CAS

Swami Dhyan Sagari

See my comment below, and thanks for the info, Guy. I do a lot of speculating on this blog. It’s good to get some data thrown in.

I hear Marlat’s MBRP referred to more and more. Can you expand on what you meant above? What do you mean “more effective in the first three months”? More effective than in later stages? Or more effective than other treatment approaches?

For those interested, here’s the MBRP home: http://www.mindfulrp.com/

I agree that meditation just feels good after awhile. After five days at this retreat thing, I feel much happier than I’ve been in ages. Or to put it another way, I feel zero depression.

MPSR outperforms Treatment As Usual for the first three months. By month four there is no difference. There is no data after month four. See slide #46 in Marlat’s PowerPoint available here:

http://www.amrig.org/presentation-materials

Hey, this is superb!!! Thanks so much.

ATTENTION EVERYONE: This is a downloadable Powerpoint presentation by Alan Marlatt, reviewing a number of treatment approaches that integrate mindfulness practice, and reporting data showing that MBRP is at the top of the heap.

Guy, What is TAU? I couldn’t find the referent for it.

See my explanation above; TAU = Treatment As Usual.

Yes, Shaun, I do remember! And I thought of that when chatting with this other guy. That is amazing news. Wonderful!

Guy’s comments above put your success in context. And that’s extremely valuable. Obviously a lot of people are thinking along these lines. Guy’s point that no one method has proven superior to any other is important to consider. On the other hand, “significant differences” are extremely hard to come by in clinical outcome research. So…our intuitions are still a good bet.

Hey, I’ve just signing up for the MBRP course here in South Africa, and we were taught a bit of this in my PG Dip.

I strongly agree with Guy that there is no one-size-fits -all magic silver bullet in addiction. As I often state: Addiction is a confluence of confounding factors that no one really has a complete understanding of. To pretend we have this thing called addiction sorted is arrogant and misguided. So when someone tells you they have all the answers, or more dangerously, the guaranteed cure, beware!

Great article, thank you for all your work. As a Buddhist monk, the connection you point to here was the reason I had someone send me your book, which was well-worth the read, and I am most grateful for your continued work in this field – I have begun to describe Buddhism as nothing more than high-level addiction therapy, which I think describes it better than any other label.

Maybe so. Apropos the comment just above. The focus in Buddhism on attachment and craving is just a big welcome sign for people trying to understand, and hopefully overcome, addiction. Thanks for joining us!

Yes, I agree it is naive to think of meditation as some sort of quick fix to hard core addiction – but then, is there really such a fix? Buddhism strives for a much loftier goal than just freedom from substance abuse – as you note in your book, most of the drugs we are addicted to exist naturally in our brains.

In that sense it can probably be likened to pulling a tree stump out of the ground with tweezers or melting a glacier with a blowtorch. Meditation may be suited to more refined work.

That being said, the general principles of meditation can and should, I think, be used to facilitate the transition to a more ordinary state – I think it would just be harder to implement them en force in early stages of recovery.

Glad to be a part of the conversation 🙂

Yes, it’s important to think about stages, though note the comment buy Guy just above. Also, I did some (home-grown) meditation during and after my years of addiction. I think it helped me in different ways at different stages — though it was never exactly a “cure”.

And what’s the right word? Lofty? Refined? Maybe….but it’s powerful stuff. I wouldn’t necessarily compare it to a tweezers. Maybe a blowtorch…

Well, one thing to note is how inexact the word “meditation” is – what Descartes did and what I do are quite different, after all…

Sometimes multiple types of meditation can be employed for different purposes. For example, one’s main practice may be in cultivating objectivity in regards to mundane experience (aka mindfulness); when a certain experience becomes overwhelming, one might switch to, say, meditation on friendliness to overcome hatred, meditation on the parts of the body to overcome lust, meditation on death to overcome laziness, or meditation on one’s spiritual teacher (e.g. the Buddha) to overcome lack-of-confidence, etc.

Powerful stuff, indeed, but so is addiction; I wasn’t thinking of tweezers as weak, just perhaps inadequate as a means of dealing with the magnitude of hardcore addiction alone – in my mind it’s more a question of one’s ability to stay ahead of the unmindful mind states, which of course is more difficult in extreme cases of addiction, than the actual efficacy of mindfulness.

By lofty I just meant that Buddhism does indeed aspire towards freedom from any and all addiction (at least on a mental level); most addiction therapy is focussed on the extremes of substance abuse, I would think, and, as most of the commenters here, makes a distinction between “positive” and “negative” desires (Buddhism, as I understand it, makes no such distinction, except as regards semantic “wants” like “wanting” to become free from wanting).

This emphasis on a much more refined sort of freedom from addiction may make meditation teachers less equipped to deal with cases of hardcore addiction (and certainly less inspired, given limited time and resources). It seems a better bet to teach meditation to GPs and psychologists and let them incorporate meditation into a broader recovery program, which may be followed up by more intensive application of meditation practice once the mind has become stabilized.

Unfortunately, the clinical emphasis on medication has created a sort of disconnect that makes the transition more difficult, I think; it is observably difficult for someone on anti-depressants to be objective to the level expected in meditation, so there needs to be a shift in how we define “stable” – is it really stable to be dependant on psychoactive drugs for the rest of one’s life? It certainly, in my experience, isn’t conducive towards enlightenment.

Or you can just surrender.

Brother Bhikkhu,

See addiction as attachment. What is the difference between attachment to alcohol and drugs and attachment to sex, money, personal possessions, intellect or spiritual growth ? ? ? ? Marlat’s research shows mindfulness MOST EFFECTIVE in early recovery (first 90 days).

Namaste,

Sagari

Hey Marc – great post and ideas – I wish I had more time to write down all that is rushing through my mind on a daily basis and then put it across so clearly as you do! I’m glad you got so much out of that PLOS article, and I to will return to it in the near future.

“addiction comes off looking like a fundamental aspect of the human condition.” So true. That is why the treatment of addiction through “vaccines” that seems to be a focus of much research these days is something I believe will raise many ethical issues. I would happily take a small-pox vaccine, but even with all the destruction my addiction caused, I would almost certainly never take an “addiction vaccine”! We have seen the mixed results from ablative surgery for opioid addictions and the corresponding lose of “self” for many. To touch addiction is to touch the essence of humanity.

Which brings me to a more controversial point:* While I embrace many of the principles of Buddhism, and I think mindfullness is an essential skill and very helpful in recovery, I think that the absence of desire would lead us to a very “empty” state. Maybe this is a point that some would like to reach, but for me, to attempt to deny one’s human frailty often leads to confirming it in the most desperate of ways. Is this state of “emptiness” not to a form of ablation through the laser-like focus of the mind?

For me, I would prefer to recognise my desires, to fully embrace their extremes and mindfully choose those I wish to pursue, and those I wish to let pass. After all, it is attachment I seek and connectedness I want, but not to anything or anyone, rather to those things and people I choose to connect to.

*I know very little about Buddhism, so perhaps my statements are missing some very valid points or are based on misinformation!

Shaun, I think you are describing a caricature of Buddhism, much like NN above. Please see my reply. It’s doubtful that sitting still for a few minutes or even hours a day would have the power to ablate anything, least of all “desire”. The Rimpoche guy I refer to in my reply to Nicolas, above, was certainly “advanced”. He just glowed. But he talked about his fears, his wishes, his feeling of emptiness, and how he sometimes tries to suck in people’s idealization of him to fill him up. The difference is, he deals with these emotional states mindfully. He lets himself watch what’s going on in his emotions. He doesn’t try to shut it down — he deliberately allows it, without letting it rule him.

You said: “For me, I would prefer to recognise my desires, to fully embrace their extremes and mindfully choose those I wish to pursue, and those I wish to let pass.”

That is a PRECISE description of what these people are preaching. And by the way, they don’t preach.

Thanks for the clarification, and you are dead right about my understanding being a caricature! I’m also pleased to see my own understanding matches what these guys are “preaching” because that makes perfect sense to me.

An interesting story from my past is about a young guy who had just converted to Christianity and was worried about the effect on his faith if he moved into a home of Buddhists. He sought the counsel of a church minister who I consider pretty wise. His advice:”you’ll probably learn more about how to live the Christian walk from a Buddhist than from most Christians”. As you say, they don’t preach!

Right on!

Hi Marc,

another beautiful post!!!

In my opinion, there is a big difference between desiring and craving something/ or someone…

I may want to achieve a goal, to visit a new country, get an ice cream; but I don’t depend on these things!!! I don’t use these things to fill my empty!!!

Instead, when I crave something, I can’t live without it!!! I need to shift my inner pain outside, and seek relief! Meditation can help to control the craving…but the emptiness remains!!! we need to become aware abuot that pain, that emptiness…and since it is resides on a subconscious level, we need some help to bring that problem on a conscious level and to deal with it and finally solve it.

Hi Valeria. Yes, that’s exactly what the Buddhists here seem to recommend. Bring that emptiness, that craving, into consciousness. Allow it to exist. Explore it. Be kind to the part of you that craves. So that we can learn to live with some of that emptiness without having to fill it up so desperately.

Seems like good advice to me.

It seems obvious to me that the biological culprit here of addiction is the mPFC or it’s misfunction (But really how do we define misfunction when all that exists in their is so relative to our culture, society, religion and commerce, that’s why I beleive that addiction fundamentally is a social disease), so silencing the mPFC through meditation and spiritual insights will most likely help. Also I wanted to ask a question about what role does the ego play in addiction? Do you think societies and cultures that promote more egoism have higher chances of addicted populace?

Thanks

Joe

Aren’t there many diseases that are systems in runaway? Gabaergic drugs seem to be the most effective in preventing kindling. (I am NOT suggesting BZ’s for addiction tx)

Oh you Buddhists. Emptiness as connectedness? Yikes.

Another caricature! Do they train you Americans to be suspicious of everything that doesn’t originate in the USA? Or Nazareth?

This article is of particular interest regarding all of the above. Here it is as requested Marc:

http://psycnet.apa.org/index.cfm?fa=buy.optionToBuy&id=2012-18077-001

Retraining the Addicted Brain: A Review of Hypothesized Neurobiological Mechanisms of Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention.

By Witkiewitz, Katie; Lustyk, M. Kathleen B.; Bowen, Sarah

Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, Jul 9 , 2012,

Abstract

Addiction has generally been characterized as a chronic relapsing condition (Leshner, 1999). Several laboratory, preclinical, and clinical studies have provided evidence that craving and negative affect are strong predictors of the relapse process. These states, as well as the desire to avoid them, have been described as primary motives for substance use. A recently developed behavioral treatment, mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP), was designed to target experiences of craving and negative affect and their roles in the relapse process. MBRP offers skills in cognitive–behavioral relapse prevention integrated with mindfulness meditation. The mindfulness practices in MBRP are intended to increase discriminative awareness, with a specific focus on acceptance of uncomfortable states or challenging situations without reacting “automatically.” A recent efficacy trial found that those randomized to MBRP, as compared with those in a control group, demonstrated significantly lower rates of substance use and greater decreases in craving following treatment. Furthermore, individuals in MBRP did not report increased craving or substance use in response to negative affect. It is important to note, areas of the brain that have been associated with craving, negative affect, and relapse have also been shown to be affected by mindfulness training. Drawing from the neuroimaging literature, we review several plausible mechanisms by which MBRP might be changing neural responses to the experiences of craving and negative affect, which subsequently may reduce risk for relapse. We hypothesize that MBRP may affect numerous brain systems and may reverse, repair, or compensate for the neuroadaptive changes associated with addiction and addictive-behavior relapse. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved)

Do you recommend a TX Center based on these principles?

You wrote “On that note, I’ll end by touching on a provocative experiment recently published in PLOS1, a prominent scientific journal [and brought to my attention by Shaun Shelly on this blog]. It’s well known that cocaine addiction causes reduced grey matter (GM) volume — thought to represent a loss of synapses — in certain regions of the cortex. But these graph copyresearchers found increasing synaptic thickness in cocaine addicts who had abstained for several months: and the longer the period of abstention, the greater the growth. Most striking of all, the new growth wasn’t simply a reversal of what was lost, like a pruned bush growing back its leaves. Rather, synaptic growth was observed in new areas — areas known to underlie reflectivity and self-control. In fact, this growth surpassed levels reached by “normal” (never-addicted) people after a period of 8-9 months, indicating the emergence of more advanced mental skills. If these results are replicated, they’ll provide solid evidence that recovery, like addiction, is a developmental process, which may benefit from the advanced cognitive capacities facilitated by mindfulness training.’

This will explain why after my last recovery I suddenly got interested in economics and financial subjects and felt a burst of brilliance while consuming large amounts of facts and ideas via countless book readings. I never graduated from college but could sit down and discuss very intricate economic systems and the derivative markets with any expert. I also used to medidate often and look for answers inside. I have since relapse and not been able to find myself in the same place again. However I have not given up and embarked upon a new journey to recovery. I was and have been a heavy cocaine user myself as well