This is an intimate, personal account, unlike my other posts. I’ve thought for a long time about whether and how to share it with you. I decided I had to try.

Picture yourself in a large, dark circular chamber, sleeping bags and cushions arranged all around the perimeter of the room, with an interesting looking (often long-haired, colourfully dressed) man or woman seated on each of them. About 25 in all. There’s a fire crackling in the middle of the room, its smoke rising to a chimney hole in the shadows high above. The shaman sits on a stool behind a little table, covered by fabrics and totems of various sorts, somewhere behind the fire. There are candles here and

Picture yourself in a large, dark circular chamber, sleeping bags and cushions arranged all around the perimeter of the room, with an interesting looking (often long-haired, colourfully dressed) man or woman seated on each of them. About 25 in all. There’s a fire crackling in the middle of the room, its smoke rising to a chimney hole in the shadows high above. The shaman sits on a stool behind a little table, covered by fabrics and totems of various sorts, somewhere behind the fire. There are candles here and  there, but the chamber is mostly dark. An assistant, sitting next to the shaman, prepares the brew, stirring a large flask of brown liquid. The shaman pours a certain amount in a cup, then beckons the next person to come and drink.

there, but the chamber is mostly dark. An assistant, sitting next to the shaman, prepares the brew, stirring a large flask of brown liquid. The shaman pours a certain amount in a cup, then beckons the next person to come and drink.

One by one, each of us goes forward and sits down on a small stool just in front of the shaman’s table. Now it’s my turn. The silence rushes in. I can barely see the man’s face,  but I sense his smile, the twinkle in his eye as he looks directly at me. He hands me an earthenware mug, and I drink the nasty tasting liquid in two gulps. I thank him by touching his hand. Then I sit back down, and the next person takes my place.

but I sense his smile, the twinkle in his eye as he looks directly at me. He hands me an earthenware mug, and I drink the nasty tasting liquid in two gulps. I thank him by touching his hand. Then I sit back down, and the next person takes my place.

By the time the last person is done, the ones who went first are beginning to make noises. Little sighs, or gasps, perhaps a low chuckle…or a fart. The person I came with (I’ll just say “my companion”) is on the sleeping bag next to mine. Nobody is going home tonight. We will lie down and sleep when the time comes. For now, we look at each other and raise our hands in a “cheers” gesture, smiling. Happy landing.

The wave of sounds makes its way around the chamber until — I feel the changes starting to happen in my own body and in the implicit motion and blending edges that begin to distort my field of vision. It’s been about 40 minutes since my drink. I’m excited, hugely intrigued, and terrified.

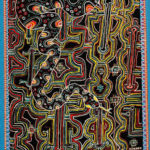

Then everything starts to change very rapidly: my perception, my thinking process, and my bodily awareness. The patterns on the prints on the far wall start to extend out into the room. Soon it’s difficult to tell which lines and whorls  are painted on fabric and which are insinuating themselves in the air all around me. Tiny noises are magnified; sounds ricochet through an echo chamber.

are painted on fabric and which are insinuating themselves in the air all around me. Tiny noises are magnified; sounds ricochet through an echo chamber.

Magic rushes in from all sides. Visual perception becomes vastly distorted: space fills with interlocking mosaics, people’s faces mutate, shifting identities, growing halos. The candle beams are fiber optic cables fraying like cotton scorched by flame. And so on and so on. I’ve tried to put the psychedelic experience into words several times. See my “Memoirs” for example. It’s not easy, but you can find many attempts at such descriptions on the net. So let’s cut to the chase.

This stuff is coming on very much like LSD. But it’s stronger. It’s happening too fast. I am overwhelmed. I wish I could turn the volume down but it keeps going up. The visual hallucinations are now so thick that I can barely see what’s actual. The wall is an arbitrary layer in a thicket of planes. As to the doors, I simply can’t find them.

This becomes a real problem when I have to go to the toilet. I’m now lying on the floor, on my side, and I can’t get up. I have no sense of balance. And I have to shit. And suddenly I realize that the urgency of the shitting, about which I’ve been warned, is right here, right now, and I have no clue what to do about it. I can’t ask for help, because I can’t find anyone in this fog of patterns. And I don’t think I can speak. I know I can’t stand up. And I don’t know which direction to crawl in.

So here comes the shit. It’s relentless, and there’s not a thing I can do about it.

Now I’m lying on the floor, somewhere, and there’s shit in my pants. I can’t figure out how much shit, but it feels like a giant mound. I imagine it has already covered the sleeping bag of one of my neighbours, though this turned out not to be true. There’s a very clear voice in my head. It’s my voice, and it’s remarkably sharp, considering my predicament. The voice says: this is an engineering problem. I have all this shit in my pants and I can’t get up or move.

I found out later that I had lain on the floor saying “oh fuck, oh fuck” several times a minute. For several hours! But what I experienced subjectively was different. I experienced PURE HELPLESSNESS. Yet there was a calmness in it. This helplessness was the ground floor of an architecture I’d lived in all my life. I can’t give you a clearer sense of what I mean except by repeating these words: paralyzed, shit, can’t see, can’t walk, can’t ask for help…and then I started getting cold. Really really cold. But there was nothing I could do about that either, since any movement (e.g., creeping toward the fire) had become much too challenging.

We were all instructed not to interfere with each other’s “trips” unless we deemed that someone was in great distress or in actual danger. (And in those cases, the assistants always seemed to get there quickly.) It was thought best to let people go through their suffering and learn what they needed to learn from it — without interruption. So, for three or four hours, I lay there and considered what pure helplessness was like. I had not experienced it since (presumably) my infancy. There was a lot to catch up on. I felt the helplessness through every part of my body and mind. I prodded it from every mental angle. I thought about it. I felt it. And I remembered it.

We know (intellectually) that we come from helplessness in infancy and return to it in old age or on our death-beds if we don’t live that long. But how can we actually live with that knowledge? How can we just be here, knowing that we could lose everything at any time? And someday we will? How can we endure this condition? And then…what other condition is there? With the plant soothing and guiding me at the deepest level, I experienced (vividly, like I was there) what it was like for my ancestors, tens and hundreds of thousands of years ago, to not be able to get warm. To be freezing cold, with no fire anywhere. I felt the ultimate fragility of all animate beings. I experienced helplessness as pure reality.

And I kept asking myself, and asking the plant who seemed a living presence, who could endure this? And the answer came when I listened to my breathing and asked (as I often still do in meditation) who is doing this breathing? This body. That’s who.

And I kept asking myself, and asking the plant who seemed a living presence, who could endure this? And the answer came when I listened to my breathing and asked (as I often still do in meditation) who is doing this breathing? This body. That’s who.

I remembered what it was like to be a small child and depend entirely on someone else to help me out of problems I could not solve. And with that came the most brutal and most enlightening realization: tonight, every time I considered calling out for help, I stopped myself, because I didn’t want to bother anyone, and because I was ashamed. I  heard my voice coil into these self-effacing, euphemistic pleas: if it wouldn’t be too much trouble…if you wouldn’t mind… In fact I could not imagine that someone (like a parent) might just want to help me. I could not trust.

heard my voice coil into these self-effacing, euphemistic pleas: if it wouldn’t be too much trouble…if you wouldn’t mind… In fact I could not imagine that someone (like a parent) might just want to help me. I could not trust.

Which neatly explained the two years of bullying and despair I’d forced myself to endure at boarding school as a teenager (before I got seriously into drugs). I could have asked my parents to get me the hell out of there. But I didn’t. Now, for the first time, I understood why.

All these insights came with a kind of intense grace or beauty despite their awfulness. The ayahuasca was unsparing, determined, but also somehow generous and loving, like a planetary caregiver.

Help came, finally, when the hallucinations abated enough for me to recognize familiar faces. Like the face of my companion and the shaman — both looking concerned. I called to them. They hoisted me up, gently, pretty much carried me to the washroom, and hosed me down in the shower. There was no warm water. I was colder than I’d ever imagined being. But they got me clean. And I had brought clean clothes. They helped me stagger back to my spot, and before too long I was almost okay. I lay down on my sleeping bag and, once the whispers faded, finally slept.

That recognition of pure helplessness hasn’t gone away completely, and it’s been a few years now. Sometimes it’s distant, sometimes (for example when meditating), it’s right there, a cosmic slap in the face. And at each of these times, during each of these replays of that first dreadful realization, I understand something about myself I’d never understood before that night. Even after ten years of twice-a-week psychotherapy in my thirties. I understand that (until quite recently) I have lived my life in denial of my helplessness — and in denial of the lack of trust that makes it so sad. My thinking skills, my determination, my obsessiveness, my drive to succeed (20+ years as a professor is no picnic) — all were weapons against helplessness. In the service of self-control.

And so was my drug-taking — because drugs are a way to deny helplessness. Drugs allow you to change things, to change how you feel. Drugs were a way to take control of my mood — my anxiety, depression, shame, fear…to vanquish them. If only for a while.

My conclusion is simple: Can taking psychedelics help us understand our addictions? Yes, but it might not be an easy ride.

My four subsequent ayahuasca trips (three in South America) weren’t nearly as difficult as that first one. And I was able to make it to the toilet each time — though sometimes at a run. Why did I ever take it again? Because I wanted to experience other facets of this strange substance and the tradition it came from. And I did. I experienced cohesion, love for those around me, beauty so intense that it made me cry, and something else I’d never felt before: pure, unfettered gratitude, gushing outward into the universe. Gratitude for something I can’t explain. I mention this because I don’t want to

My four subsequent ayahuasca trips (three in South America) weren’t nearly as difficult as that first one. And I was able to make it to the toilet each time — though sometimes at a run. Why did I ever take it again? Because I wanted to experience other facets of this strange substance and the tradition it came from. And I did. I experienced cohesion, love for those around me, beauty so intense that it made me cry, and something else I’d never felt before: pure, unfettered gratitude, gushing outward into the universe. Gratitude for something I can’t explain. I mention this because I don’t want to  leave you with the impression that psychedelics can only be valuable for the pain they release. They can also be valuable for connecting us with the goodness inside and outside ourselves.

leave you with the impression that psychedelics can only be valuable for the pain they release. They can also be valuable for connecting us with the goodness inside and outside ourselves.

That might be another important way to help people move beyond their addictions. But more on that another time.

Leave a Reply