Not to be confused with the 12 steps, but read on.

Two posts ago I said I’d suggest practical applications for some of Jordan Peterson’s self-help recommendations, as they might apply to people struggling with addiction. I hesitate to put Peterson’s  name in the title of this post, as there has been such a fantastic degree of controversy surrounding this man.

name in the title of this post, as there has been such a fantastic degree of controversy surrounding this man.

Many thousands have thanked him for live-saving advice, women as well as men. Many love him, I’d say for good reasons. And many hate him. Despite my admiration for most of Peterson’s proposals, I also find myself turned off by some of the things he says in public. These seem careless, absent-minded, maybe provocative,  sometimes angry, but certainly not intended to harm vulnerable individuals. But again, I want to avoid the political shit storm. It just doesn’t interest me as much as the content of Peterson’s proposals and their capacity to help those in need.

sometimes angry, but certainly not intended to harm vulnerable individuals. But again, I want to avoid the political shit storm. It just doesn’t interest me as much as the content of Peterson’s proposals and their capacity to help those in need.

The first recommendation I want to explore is the theme of taking small, manageable steps out of addiction. To paraphrase from my previous post:

People in addiction often want to make a massive change in their lives, but the change is so massive that it overwhelms their capacity for self-direction. So they fail, again and again.

As noted previously, Peterson’s approach to the problem comes to the surface in this talk, about 33 minutes in:

You need a goal, but we don’t want your distance from the goal to crush you…Set a high aim, but differentiate it down so you know what the next step is. And then make the next step difficult enough so that you have to push yourself past where you are, but also provide yourself with a reasonable probability of success.

Nothing particularly new about this idea? Except that Peterson urges a balance between idealized progress and the capacity to succeed even minimally. People in addiction know the price of repeated failures. Each time we set a goal (e.g., never again, not tonight, not this weekend, not shooting it, stopping after two drinks,  sticking to wine) and fail to follow through, there’s a dash of salt in the already-gaping wound to our self-respect. More evidence for that critical inner voice (which I’ll get to next post) and confirmation of the belief that we’ll never succeed or we’re not worth the effort (and pain) of repeated attempts.

sticking to wine) and fail to follow through, there’s a dash of salt in the already-gaping wound to our self-respect. More evidence for that critical inner voice (which I’ll get to next post) and confirmation of the belief that we’ll never succeed or we’re not worth the effort (and pain) of repeated attempts.

These outcomes are both familiar and devastating. When I was taking drugs, each and every time I promised myself to stop — and didn’t — deepened the pit of hopelessness and self-contempt. Stopping was just too difficult…at first. “Never again” felt like being cast on the shore of a desert island, naked, alone, and lacking the one source of safety I could have brought with me.

Little steps — cutting down, controlled use — will be far more manageable for most people in active addiction. Call it harm reduction, if you like, because it certainly reduces harm. But, as Peterson emphasizes, this isn’t a rationale for falling short of  complete success. Getting your life exactly where you want it to be is possible, in fact necessary, but it might not be possible this week. So, he advises, be really practical, identify a goal that’s in reach. And make sure you stick to it. If your house is a veritable pig sty, set yourself the goal of gathering the laundry off the bedroom floor — just that — and tomorrow you’ll feel capable of tackling the sock drawer.

complete success. Getting your life exactly where you want it to be is possible, in fact necessary, but it might not be possible this week. So, he advises, be really practical, identify a goal that’s in reach. And make sure you stick to it. If your house is a veritable pig sty, set yourself the goal of gathering the laundry off the bedroom floor — just that — and tomorrow you’ll feel capable of tackling the sock drawer.

One of my clients is a man I’ll call Jason, a sixty-plus year-old who lives in a large European city, having left his home in the U.S. more than twenty years ago. We have a psychotherapy session usually  once a week via live chat on the net. Jason would score a gram of heroin almost every Friday afternoon, because the weekend stretching out ahead of him felt like a wasteland of boredom and loneliness. When he got home from work Friday he’d get high. Then he’d use the rest on Saturday. There might be enough for a small hit on Sunday, but by then things were already looking pretty grim. Every Monday came the crashing depression of going without, compounded by exhaustion (not sleeping well) and savage self-recrimination. This generally went on until Wednesday morning.

once a week via live chat on the net. Jason would score a gram of heroin almost every Friday afternoon, because the weekend stretching out ahead of him felt like a wasteland of boredom and loneliness. When he got home from work Friday he’d get high. Then he’d use the rest on Saturday. There might be enough for a small hit on Sunday, but by then things were already looking pretty grim. Every Monday came the crashing depression of going without, compounded by exhaustion (not sleeping well) and savage self-recrimination. This generally went on until Wednesday morning.

The habit was entrenched. He did this every week. The emotional vulnerability, combined with habit strength, sunk him every Friday. So we set a goal that he felt he could manage. This week, just this  week, he was to make a plan to go out with a friend on Friday evening. I helped by calling him Friday morning to make sure he was on track. By Friday at dinnertime his dealer was off duty. All he had to do was to make it till then.

week, he was to make a plan to go out with a friend on Friday evening. I helped by calling him Friday morning to make sure he was on track. By Friday at dinnertime his dealer was off duty. All he had to do was to make it till then.

We did not try to resolve whether he would use later that weekend, or the following week. He’d cross that bridge when he came to it. (The one-day-at-a-time idea is certainly familiar in the 12-step world, though it comes with spring-loaded rebuke for failing.)

This goal was in range. It was possible. And he succeeded. Saturday happened to be a sunny day and he spent it well. By Sunday there was no intense longing. Tomorrow would be a workday. Work organized Jason’s life. He wouldn’t feel tempted to use again until next Friday.

This goal was in range. It was possible. And he succeeded. Saturday happened to be a sunny day and he spent it well. By Sunday there was no intense longing. Tomorrow would be a workday. Work organized Jason’s life. He wouldn’t feel tempted to use again until next Friday.

A good start.

Obviously this isn’t rocket science. But it is powerful. Jason felt good about himself. By Sunday, and through the week, his mood was brighter than it had been in months. And he had the beginnings of a defense, a bulwark, against the self-denigrating voice that made him feel like shit most of the time.

As Peterson recognizes, as any good psychologist practicing CBT ought to know, small changes build momentum, allowing for a lot more progress than can be envisioned from Square One.

……………..

Check out this cute Medium post showing how small changes to bad habits can generate a chain reaction. Just as good habits lead to the strengthening of additional good habits, indulging in addictive acts leads to more addictive acts. It’s that simple.

I find it impossible to reflect on these cognitive calculations without considering the internal dialogue. See next post.

………………….

By the way, here is a positive and constructive website/blog from a recovered heroin addict — now a neuroscientist. No, not a cousin.

Think of everyday concepts like, say, arguments. We tend to think of an argument as a war, with a winner and a loser, and a certain amount of damage. The war metaphor gives the concept “argument” its meaning. It’s not a matter of listening or sharing; it’s something you either win or lose. How do we conceptualize “communication”? Often as a conduit, a tube connecting speaker and listener. If you see communication as a conduit, then your main concern is sending a message down the tube and having it

Think of everyday concepts like, say, arguments. We tend to think of an argument as a war, with a winner and a loser, and a certain amount of damage. The war metaphor gives the concept “argument” its meaning. It’s not a matter of listening or sharing; it’s something you either win or lose. How do we conceptualize “communication”? Often as a conduit, a tube connecting speaker and listener. If you see communication as a conduit, then your main concern is sending a message down the tube and having it  received at the other end. A failure in communication is seen as an obstruction or break in the tube. But if our metaphor for communication were different, say a pool of water encompassing speaker and listener, then we’d view communication failures in a completely different way. Maybe as a drought.

received at the other end. A failure in communication is seen as an obstruction or break in the tube. But if our metaphor for communication were different, say a pool of water encompassing speaker and listener, then we’d view communication failures in a completely different way. Maybe as a drought. Containers are either very full or partly full or partly empty or very empty. See the point? The only other attribute that comes to mind is “leakiness”. If you suffer from anxiety rather than depression, this may strike a chord.

Containers are either very full or partly full or partly empty or very empty. See the point? The only other attribute that comes to mind is “leakiness”. If you suffer from anxiety rather than depression, this may strike a chord. So you wake up in the morning and you feel empty. You say to yourself: shit, I feel so empty. I’d really like to feel more full. So I will take a drug or a drink to fill myself up. Maybe not right now but soon. I really dislike this sense of emptiness so I will put something

So you wake up in the morning and you feel empty. You say to yourself: shit, I feel so empty. I’d really like to feel more full. So I will take a drug or a drink to fill myself up. Maybe not right now but soon. I really dislike this sense of emptiness so I will put something  into my self to fill it up. If you’ve ever been in addiction you know exactly what I mean. Yet the reason we feel “empty” in the first place — rather than, say, uninvolved, or emotional, or out of sorts — is because of the container metaphor. Empty containers need to be filled up.

into my self to fill it up. If you’ve ever been in addiction you know exactly what I mean. Yet the reason we feel “empty” in the first place — rather than, say, uninvolved, or emotional, or out of sorts — is because of the container metaphor. Empty containers need to be filled up. touch or pat yourself (on the outside). You’ll find that you are in fact very full. Of stuff. Tissue and muscles and blood and bone, or, maybe more to the point, you are full of chemicals; neurotransmitters (including opioids!) coursing around inside your body constantly. If you are a container, you’re certainly not an empty one.

touch or pat yourself (on the outside). You’ll find that you are in fact very full. Of stuff. Tissue and muscles and blood and bone, or, maybe more to the point, you are full of chemicals; neurotransmitters (including opioids!) coursing around inside your body constantly. If you are a container, you’re certainly not an empty one. their synapses. Or the mental activity that moves through them. The self is open, yet containers are (or can be) closed. So maybe we can experience the self as something like an antenna or radar dish or…I don’t know…something very uncontainerlike.

their synapses. Or the mental activity that moves through them. The self is open, yet containers are (or can be) closed. So maybe we can experience the self as something like an antenna or radar dish or…I don’t know…something very uncontainerlike. metaphor: the container becomes something more like a wide, rich, pipeline connecting “you” to everything else — an open passage.

metaphor: the container becomes something more like a wide, rich, pipeline connecting “you” to everything else — an open passage.

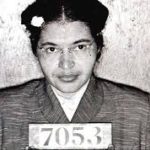

hierarchies as a product of our evolution rather than the construction of an oppressive (white, male) culture. He distinguishes sex differences, which are (he claims and I certainly agree) rooted in biology and evolution, from the social construction of gender. He analyzes the personality traits associated with women and men and argues that the asymmetrical distribution of these traits (something you may have studied in Psych 101) has much to do with the gender pay gap — which is therefore not simply a result of sexism. He certainly doesn’t deny the existence of sexism, or oppression by dominant cultural forces, or the rights of transgender people. Not at all. Yet his infusion of statistically validated facts and an evolutionary perspective into the ideological battles raging (especially in the universities) about diversity, gender, social justice and so forth has alienated and angered many on the left.

hierarchies as a product of our evolution rather than the construction of an oppressive (white, male) culture. He distinguishes sex differences, which are (he claims and I certainly agree) rooted in biology and evolution, from the social construction of gender. He analyzes the personality traits associated with women and men and argues that the asymmetrical distribution of these traits (something you may have studied in Psych 101) has much to do with the gender pay gap — which is therefore not simply a result of sexism. He certainly doesn’t deny the existence of sexism, or oppression by dominant cultural forces, or the rights of transgender people. Not at all. Yet his infusion of statistically validated facts and an evolutionary perspective into the ideological battles raging (especially in the universities) about diversity, gender, social justice and so forth has alienated and angered many on the left. staunchly elevates free speech over “sensitivity” to the feelings of others. In

staunchly elevates free speech over “sensitivity” to the feelings of others. In  As a result of his stated positions, Peterson has been mobbed by what he terms “social justice warriors”– people who espouse extreme leftist views. There’s no doubt that he disagrees with many of their views and he’s angry at the insulting nature of their attacks on him. He’s literally been shouted down on more than a few campuses. Does that make him a right-winger? Not yet. The view of Peterson as a (perhaps extreme) right-winger comes from the next act in this play. People

As a result of his stated positions, Peterson has been mobbed by what he terms “social justice warriors”– people who espouse extreme leftist views. There’s no doubt that he disagrees with many of their views and he’s angry at the insulting nature of their attacks on him. He’s literally been shouted down on more than a few campuses. Does that make him a right-winger? Not yet. The view of Peterson as a (perhaps extreme) right-winger comes from the next act in this play. People  who really do identify with the right, including the far right, started to proclaim their undying loyalty to Peterson, mainly because the far left seems to hate him so much. In my view, the equation is simple. If my enemy hates you then you must be my friend. Does that make him a right-winger?

who really do identify with the right, including the far right, started to proclaim their undying loyalty to Peterson, mainly because the far left seems to hate him so much. In my view, the equation is simple. If my enemy hates you then you must be my friend. Does that make him a right-winger? too much about the fallout. I personally don’t think he enjoys being in the centre of this altercation one bit. He’s said many times in public that he’d rather people listen to, and argue with, the content of his arguments than slot him into a political ideology.

too much about the fallout. I personally don’t think he enjoys being in the centre of this altercation one bit. He’s said many times in public that he’d rather people listen to, and argue with, the content of his arguments than slot him into a political ideology. surely knows. (When Trump got elected, I wrote a post entitled “Oh Shit.” I was depressed for weeks and made no secret of it.) But that doesn’t mean I have nothing to discuss with people who see things differently. And more to the point, this blog isn’t about politics. It’s about experiential, social, psychological, and neurobiological approaches to understanding addiction. I’d be glad to chat with anyone out there about the the political eruptions surrounding Peterson’s public persona. I’m sure I can learn something. Maybe over a coffee if I’m ever in your part of the world.

surely knows. (When Trump got elected, I wrote a post entitled “Oh Shit.” I was depressed for weeks and made no secret of it.) But that doesn’t mean I have nothing to discuss with people who see things differently. And more to the point, this blog isn’t about politics. It’s about experiential, social, psychological, and neurobiological approaches to understanding addiction. I’d be glad to chat with anyone out there about the the political eruptions surrounding Peterson’s public persona. I’m sure I can learn something. Maybe over a coffee if I’m ever in your part of the world. But I think it would be a shame to ward off Peterson’s ideas as if he were some sort of vampire, simply because of the political accusations flying back and forth. I don’t agree with everything Peterson says. In my review, soon to come out, I firmly criticize him for cherry-picking scientific factoids to support dubious assumptions and for a style of argument which violates the standards of scientific discourse — namely basing one’s authority on intuitions rather than methodical arguments grounded in data. Yet some of his ideas strike me as valid, powerful, refreshing, constructive, and of particular utility for enhancing personal growth. Whether you consider yourself to be on the right or on the left, it seems there’s much of value here, and I hope you won’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.

But I think it would be a shame to ward off Peterson’s ideas as if he were some sort of vampire, simply because of the political accusations flying back and forth. I don’t agree with everything Peterson says. In my review, soon to come out, I firmly criticize him for cherry-picking scientific factoids to support dubious assumptions and for a style of argument which violates the standards of scientific discourse — namely basing one’s authority on intuitions rather than methodical arguments grounded in data. Yet some of his ideas strike me as valid, powerful, refreshing, constructive, and of particular utility for enhancing personal growth. Whether you consider yourself to be on the right or on the left, it seems there’s much of value here, and I hope you won’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.

commissioned by the

commissioned by the  after publication. A professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, Peterson has been cheered and even glorified for his radical approach to self-improvement — presented in his new book and his many online lectures. What he proposes is a set of guidelines highlighting self-honesty, personal responsibility, and what we in the addiction world have long emphasized as

after publication. A professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, Peterson has been cheered and even glorified for his radical approach to self-improvement — presented in his new book and his many online lectures. What he proposes is a set of guidelines highlighting self-honesty, personal responsibility, and what we in the addiction world have long emphasized as  the bedrock of growth, empowerment — believing in your own intentions, intuitions and capacities for change. But Peterson has also been a lighting-rod for criticism. His detractors claim that he is anti-feminist, anti-LGBT, anti-social justice, and a voice

the bedrock of growth, empowerment — believing in your own intentions, intuitions and capacities for change. But Peterson has also been a lighting-rod for criticism. His detractors claim that he is anti-feminist, anti-LGBT, anti-social justice, and a voice  for the politically incorrect (shudder) alt-right. This reaction has activated a subset of Peterson followers who are indeed highly conservative or libertarian, and sometimes quite vicious in their attacks on Peterson’s critics. But we have to extract Peterson’s message from the surrounding political hubbub. In my view he’s neither left-wing nor right-wing. As I emphasize in my review, he speaks as an individual, not a political movement.

for the politically incorrect (shudder) alt-right. This reaction has activated a subset of Peterson followers who are indeed highly conservative or libertarian, and sometimes quite vicious in their attacks on Peterson’s critics. But we have to extract Peterson’s message from the surrounding political hubbub. In my view he’s neither left-wing nor right-wing. As I emphasize in my review, he speaks as an individual, not a political movement.

internal dialogue.

internal dialogue. that you have to push yourself past where you are, but also provide yourself with a reasonable probability of success.

that you have to push yourself past where you are, but also provide yourself with a reasonable probability of success. suggest something to set in order, which you could set in order…voluntarily, without resentment.” In other words, with a little work, that voice can become a valuable ally.

suggest something to set in order, which you could set in order…voluntarily, without resentment.” In other words, with a little work, that voice can become a valuable ally. wisdom of a good clinical psychologist. He also ties his ideas to compelling lines of thought from philosophy (especially Nietzsche), social science, evolutionary theory, and even religion. A fascinating thinker, overall, with an especially helpful perspective for refashioning psychological approaches to addiction.

wisdom of a good clinical psychologist. He also ties his ideas to compelling lines of thought from philosophy (especially Nietzsche), social science, evolutionary theory, and even religion. A fascinating thinker, overall, with an especially helpful perspective for refashioning psychological approaches to addiction.

Anyway, just this morning it occurred to me that I forgot to let you guys know that the Great Debate is finally available on YouTube.

Anyway, just this morning it occurred to me that I forgot to let you guys know that the Great Debate is finally available on YouTube.  But THRIVE really isn’t much different from hundreds of similar organizations springing up around the US, largely in response to the opioid/overdose epidemic. THRIVE mainly helps steer users and families to nonprofit organizations (supported by public funds and donations) dedicated to rehab, recovery, abstinence and above all harm reduction. These are incredibly dedicated groups, and the four people selected to speak for them were smart, passionate, hugely knowledgeable and deeply concerned. For the many people crowding the room — the wasted looking former or “recovering” addicts who’d been driven too far down for too long, the people of all ages with half a spark in their eye who’d remained alive and involved thanks largely to methadone and Suboxone, the family members still brimming with hope or anguish and sometimes gratitude, the teachers from local colleges, the front-line workers and those in training to become addiction workers, organizers and lobbyists, cops who cared, even government people (there was a state senator in attendance, and everyone seemed to know him because he was something of a regular) — for all those people, THRIVE and its tributaries were the main act. Not NIDA or ASAM or the Center for Disease Control, not AA or SMART, not Drug Courts, not psychologists (like me) or psychiatrists who think they might help explain things better. The main act was the community, right there in that room, palpable as a community, whose only goal was to help.

But THRIVE really isn’t much different from hundreds of similar organizations springing up around the US, largely in response to the opioid/overdose epidemic. THRIVE mainly helps steer users and families to nonprofit organizations (supported by public funds and donations) dedicated to rehab, recovery, abstinence and above all harm reduction. These are incredibly dedicated groups, and the four people selected to speak for them were smart, passionate, hugely knowledgeable and deeply concerned. For the many people crowding the room — the wasted looking former or “recovering” addicts who’d been driven too far down for too long, the people of all ages with half a spark in their eye who’d remained alive and involved thanks largely to methadone and Suboxone, the family members still brimming with hope or anguish and sometimes gratitude, the teachers from local colleges, the front-line workers and those in training to become addiction workers, organizers and lobbyists, cops who cared, even government people (there was a state senator in attendance, and everyone seemed to know him because he was something of a regular) — for all those people, THRIVE and its tributaries were the main act. Not NIDA or ASAM or the Center for Disease Control, not AA or SMART, not Drug Courts, not psychologists (like me) or psychiatrists who think they might help explain things better. The main act was the community, right there in that room, palpable as a community, whose only goal was to help.

with a counselor who actually cares. What I learned is that my arguments about the “disease” label of addiction were entirely context-specific. They may have their place with scientists, doctors, and policy makers. But here on the street, the disease label meant nothing more than a ticket to get help. The word was simply a currency, coinage — and if you had to use it to qualify for treatment, then so be it.

with a counselor who actually cares. What I learned is that my arguments about the “disease” label of addiction were entirely context-specific. They may have their place with scientists, doctors, and policy makers. But here on the street, the disease label meant nothing more than a ticket to get help. The word was simply a currency, coinage — and if you had to use it to qualify for treatment, then so be it. I’ll end with a

I’ll end with a