I didn’t think I’d do another blog post for a few weeks, but I am learning so much about addiction — from gamblers! — I have to share it with you.

Gambling really is a problem in Australia, and here’s what it looks like. The night before last I was walking around Melbourne, searching for a restaurant, when someone pointed me to the casino — a magnificent building with an enormous neon crown emblazoned on its glass and concrete exterior. The Crown Casino. I entered, past smiling security guards, and strolled down a central corridor infested with slot machines, one glittering gallery after another branching off it. Different rooms sported different games:

Gambling really is a problem in Australia, and here’s what it looks like. The night before last I was walking around Melbourne, searching for a restaurant, when someone pointed me to the casino — a magnificent building with an enormous neon crown emblazoned on its glass and concrete exterior. The Crown Casino. I entered, past smiling security guards, and strolled down a central corridor infested with slot machines, one glittering gallery after another branching off it. Different rooms sported different games:  roulette, baccarat, poker, some blackjack tables, but the most riveting signs above each table announced minimum bets per hand: $50, $100, $200, $500. Per hand! (at one point I located a $10 blackjack table and calmly surrendered my $50 stake.)

roulette, baccarat, poker, some blackjack tables, but the most riveting signs above each table announced minimum bets per hand: $50, $100, $200, $500. Per hand! (at one point I located a $10 blackjack table and calmly surrendered my $50 stake.)

The roulette and card tables weren’t really that interesting. Very rich, mostly Chinese people stood around throwing away tremendous amounts of money, not much moved either by winning or by losing.

But there were some roulette tables where one or two dowdy looking men stood, intently calculating. Just before each spin they would spread their chips in some intricate cabalistic pattern of numbered squares and  intersecting lines. And when the wheel slowed down and the white ball finally settled, it mattered. You’d either see a flash of triumph or else despair. And sometimes a protest:

intersecting lines. And when the wheel slowed down and the white ball finally settled, it mattered. You’d either see a flash of triumph or else despair. And sometimes a protest:

“Oh fuck, again?! You couldn’t do me a favour this once!” shouted one man, only slightly conspicuous by the sweat stains in his armpits.

And then he’d shovel another $50 or $100 at the dealer and get another pile of chips in return.

“Who was he angry at?” I asked the dealer, after the guy stormed away. “Is he angry at you?”

“I’m just doing my job,” the young man replied. He looked like he might be working his way through law school.

“Yeah, but they know that, right? And they know that whatever number comes up is completely random, right?”

“Sure, they know it, rationally they know it, but they still think they’ve figured out the pattern. And I don’t know why that guy was so mad. He won a thousand bucks in the last hour.”

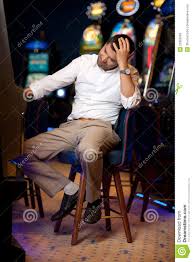

I think his anger came from shame. Losing makes you a loser, especially when someone’s watching. But the most horrific sights in the casino were the slot machines. These high-tech electronic monsters are designed to instill a sense of triumph while you continue to lose your shirt. Men and women of all ethnicities and incomes sat there and hit one of a short row of buttons mindlessly, repeatedly, watching their net balance dwindle, roll by roll. But with occasional rebounds — accompanied by flashing lights, prancing cartoon nudes, and peppy  jingles. Only to continue their downward journey a moment later. I watched a middle-aged Eastern-European couple shovel bills into the slim mouth of the machine every few minutes and keep on playing. Did they actually think they would win? I asked them that. The man told me to go away.

jingles. Only to continue their downward journey a moment later. I watched a middle-aged Eastern-European couple shovel bills into the slim mouth of the machine every few minutes and keep on playing. Did they actually think they would win? I asked them that. The man told me to go away.

What was so spooky about this robotic ritual was the flatness of the facial expressions. The players hardly reacted to winning — or losing. Their expressions didn’t change. They just kept punching those buttons, every time the machine reset, which was every few seconds. And for them it mattered.

Losers eventually have to give up. Then they go home and lie to their loved ones, take out another loan or ratchet up their credit card maximum, and come back to press that button again in a few more days. The only time you see emotion on their faces is when they finally stop, transfigured by despair and disgust.

Losers eventually have to give up. Then they go home and lie to their loved ones, take out another loan or ratchet up their credit card maximum, and come back to press that button again in a few more days. The only time you see emotion on their faces is when they finally stop, transfigured by despair and disgust.

Nobody has to tell you that gambling is addictive. It’s obvious. But here’s what I learned that night and in my readings and discussions since then:

First off, the compulsive slot-machine players looked exactly like end-stage drug addicts. People who snort or shoot up hour after hour or minute after minute. They’d display almost no pleasure. And then, when it was all gone, they’d go out to score, because that’s just the next step. I’m reminded of a guy  bedded in the cot next to mine in a cheap hippie hotel in Delhi, many years ago. This guy would rise up on his bed, reach down below for his carton of morphine ampoules, break the top off one of them, load it, shoot it, and then lie back down for almost exactly four hours. Until he started to twitch. Then he’d do it again.

bedded in the cot next to mine in a cheap hippie hotel in Delhi, many years ago. This guy would rise up on his bed, reach down below for his carton of morphine ampoules, break the top off one of them, load it, shoot it, and then lie back down for almost exactly four hours. Until he started to twitch. Then he’d do it again.

Maia Szalavitz calls it the hedonic treadmill. And it’s got everything to do with our standard biological computations. It’s about dopamine and reward prediction error. If the reward is the same or less than what was anticipated, the dopamine surge that came with anticipation drops back down to zero. With heroin, that takes place soon after you get the rush, the buzz…once you realize “oh this is all it is? — Now what?” With coke you get it in a few minutes, once you perceive that this little bump was merely a flash in the pan. False advertising. Ice-cream melting. But with gambling?! These folks lose almost every bet, and the bets they win are tiny.

So that’s the exaltation offered by gambling.

But then there’s the longer-term loss. The loss you feel when you get up after you’ve given up and look in your wallet (as if you had to) and realize that you lost it all.

Then there’s the blunting. I won’t get into that here, but addiction neuroscience is pretty clear that dopamine receptors thin out with all that action, so all rewards — both those provided by the addiction and those provided by pizza, sex, and playing with your dog — become flattened, diminished, boring. In which case, all you can do is to take bigger hits (more coke, more smack, or bigger bets at the tables) or else — finally, once you’ve had enough — quit. (Note that disease-model advocates conflate this effect with tolerance, which often rises in parallel though it’s not the same thing.)

And then there’s the really long-term loss: the loss of self-esteem. That’s the shame and mortification and self-disgust that shrouds you the way mist clings to the branches of a dying tree. That’s what gave rise to the rage of mister sweaty-armpits roulette player — anger borne of shame. That’s what gave rise to the despair shown by the couple with the Eastern-European accents as they staggered away from the slot machine, the machine that betrayed them.

Sound familiar?

I’m off to Australia for two weeks. I’ll be doing talks, public debates, etc, on the subject of gambling as well as substance addiction. Apparently gambling is a more serious public health issue than alcohol or drug addiction in Australia. I’ll also be spending some time on a farm somewhere where they shear sheep and herd cows. Should be a nice break from urban life in Holland.

I’m off to Australia for two weeks. I’ll be doing talks, public debates, etc, on the subject of gambling as well as substance addiction. Apparently gambling is a more serious public health issue than alcohol or drug addiction in Australia. I’ll also be spending some time on a farm somewhere where they shear sheep and herd cows. Should be a nice break from urban life in Holland.

Picture yourself in a large, dark circular chamber, sleeping bags and cushions arranged all around the perimeter of the room, with an interesting looking (often long-haired, colourfully dressed) man or woman seated on each of them. About 25 in all. There’s a fire crackling in the middle of the room, its smoke rising to a chimney hole in the shadows high above. The shaman sits on a stool behind a little table, covered by fabrics and totems of various sorts, somewhere behind the fire. There are candles here and

Picture yourself in a large, dark circular chamber, sleeping bags and cushions arranged all around the perimeter of the room, with an interesting looking (often long-haired, colourfully dressed) man or woman seated on each of them. About 25 in all. There’s a fire crackling in the middle of the room, its smoke rising to a chimney hole in the shadows high above. The shaman sits on a stool behind a little table, covered by fabrics and totems of various sorts, somewhere behind the fire. There are candles here and  there, but the chamber is mostly dark. An assistant, sitting next to the shaman, prepares the brew, stirring a large flask of brown liquid. The shaman pours a certain amount in a cup, then beckons the next person to come and drink.

there, but the chamber is mostly dark. An assistant, sitting next to the shaman, prepares the brew, stirring a large flask of brown liquid. The shaman pours a certain amount in a cup, then beckons the next person to come and drink. but I sense his smile, the twinkle in his eye as he looks directly at me. He hands me an earthenware mug, and I drink the nasty tasting liquid in two gulps. I thank him by touching his hand. Then I sit back down, and the next person takes my place.

but I sense his smile, the twinkle in his eye as he looks directly at me. He hands me an earthenware mug, and I drink the nasty tasting liquid in two gulps. I thank him by touching his hand. Then I sit back down, and the next person takes my place. are painted on fabric and which are insinuating themselves in the air all around me. Tiny noises are magnified; sounds ricochet through an echo chamber.

are painted on fabric and which are insinuating themselves in the air all around me. Tiny noises are magnified; sounds ricochet through an echo chamber. And I kept asking myself, and asking the plant who seemed a living presence, who could endure this? And the answer came when I listened to my breathing and asked (as I often still do in meditation) who is doing this breathing? This body. That’s who.

And I kept asking myself, and asking the plant who seemed a living presence, who could endure this? And the answer came when I listened to my breathing and asked (as I often still do in meditation) who is doing this breathing? This body. That’s who. heard my voice coil into these self-effacing, euphemistic pleas: if it wouldn’t be too much trouble…if you wouldn’t mind… In fact I could not imagine that someone (like a parent) might just want to help me. I could not trust.

heard my voice coil into these self-effacing, euphemistic pleas: if it wouldn’t be too much trouble…if you wouldn’t mind… In fact I could not imagine that someone (like a parent) might just want to help me. I could not trust. My four subsequent ayahuasca trips (three in South America) weren’t nearly as difficult as that first one. And I was able to make it to the toilet each time — though sometimes at a run. Why did I ever take it again? Because I wanted to experience other facets of this strange substance and the tradition it came from. And I did. I experienced cohesion, love for those around me, beauty so intense that it made me cry, and something else I’d never felt before: pure, unfettered gratitude, gushing outward into the universe. Gratitude for something I can’t explain. I mention this because I don’t want to

My four subsequent ayahuasca trips (three in South America) weren’t nearly as difficult as that first one. And I was able to make it to the toilet each time — though sometimes at a run. Why did I ever take it again? Because I wanted to experience other facets of this strange substance and the tradition it came from. And I did. I experienced cohesion, love for those around me, beauty so intense that it made me cry, and something else I’d never felt before: pure, unfettered gratitude, gushing outward into the universe. Gratitude for something I can’t explain. I mention this because I don’t want to  leave you with the impression that psychedelics can only be valuable for the pain they release. They can also be valuable for connecting us with the goodness inside and outside ourselves.

leave you with the impression that psychedelics can only be valuable for the pain they release. They can also be valuable for connecting us with the goodness inside and outside ourselves.

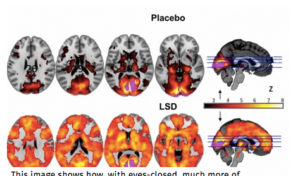

off from each other, doing their own (quasi-independent) thing. We don’t really know how this affects cognition, but participants who showed the greatest increase in cross-brain

off from each other, doing their own (quasi-independent) thing. We don’t really know how this affects cognition, but participants who showed the greatest increase in cross-brain  synchrony also reported greater “ego dissolution.” That makes sense. According to the lead researcher, David Nutt, “The drug can be seen as reversing the more restricted thinking we develop from infancy to adulthood…” Nutt concluded that LSD “could pull the brain out of thought patterns seen in depression and addiction.” (quotes and paraphrasing from

synchrony also reported greater “ego dissolution.” That makes sense. According to the lead researcher, David Nutt, “The drug can be seen as reversing the more restricted thinking we develop from infancy to adulthood…” Nutt concluded that LSD “could pull the brain out of thought patterns seen in depression and addiction.” (quotes and paraphrasing from  present age. Many young people know about it, some have taken it, and the reports of users are (as usual) controversial. Some have had a bad trip, some have been duped by fake shamans, but the majority have huge respect for this natural herbal brew. Many feel it has been transformative in their lives. Shamans in South America have used ayahuasca for centuries to help treat ailments of the mind or the spirit, and it is also regarded by today’s youth as “healing.” Yet for many ayahuasca drinkers, there is nothing overt that needs to be healed. For them, ayahuasca is an opportunity to learn deep lessons about who they are and how they connect to the world.

present age. Many young people know about it, some have taken it, and the reports of users are (as usual) controversial. Some have had a bad trip, some have been duped by fake shamans, but the majority have huge respect for this natural herbal brew. Many feel it has been transformative in their lives. Shamans in South America have used ayahuasca for centuries to help treat ailments of the mind or the spirit, and it is also regarded by today’s youth as “healing.” Yet for many ayahuasca drinkers, there is nothing overt that needs to be healed. For them, ayahuasca is an opportunity to learn deep lessons about who they are and how they connect to the world. Many with addictions have gone to ayahuasca for help. And the renowned addiction expert, Gabor Maté,

Many with addictions have gone to ayahuasca for help. And the renowned addiction expert, Gabor Maté,  in the 60s and 70s. I think these experiences were useful to me in various ways, but they certainly didn’t smooth out all the rough edges. I suppose my last acid trip was some time in my thirties. Then I stopped. Been there, done that. But what’s all the fuss about ayahuasca? Is it really different in some fundamental way? I wanted to find out.

in the 60s and 70s. I think these experiences were useful to me in various ways, but they certainly didn’t smooth out all the rough edges. I suppose my last acid trip was some time in my thirties. Then I stopped. Been there, done that. But what’s all the fuss about ayahuasca? Is it really different in some fundamental way? I wanted to find out.

there is increasing opposition to court-ordered attendance at 12-step groups, and the glaring discrepancy between the brain disease model and 12-step methods continues to…well, glare. At the interface between science and treatment, there’s new thinking about the benefits of psychedelics, new research on how meditation changes the brain, investigation of smartphone apps that might help control urges, and increasing precision in the debate between the disease model and the learning model — as both sides advance their weaponry.

there is increasing opposition to court-ordered attendance at 12-step groups, and the glaring discrepancy between the brain disease model and 12-step methods continues to…well, glare. At the interface between science and treatment, there’s new thinking about the benefits of psychedelics, new research on how meditation changes the brain, investigation of smartphone apps that might help control urges, and increasing precision in the debate between the disease model and the learning model — as both sides advance their weaponry. finding that cognition, emotion, and behaviour can’t be clearly differentiated in brain structure or function. They overlap entirely.

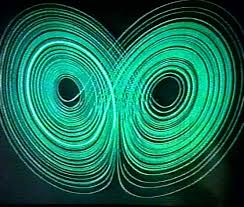

finding that cognition, emotion, and behaviour can’t be clearly differentiated in brain structure or function. They overlap entirely. To explore that question, let me tell you how scientists define a habit. And for that, we need to take a brief tour of complexity theory. According to complexity theory, a habit is a stable state in a complex system — a system composed of many interacting parts. Complex systems — such as ecosystems, societies, cultures, family dynamics, flocks of birds, herds of cattle, individual minds, individual bodies, and certainly individual brains — are made up of components (birds in a flock, family members at the

To explore that question, let me tell you how scientists define a habit. And for that, we need to take a brief tour of complexity theory. According to complexity theory, a habit is a stable state in a complex system — a system composed of many interacting parts. Complex systems — such as ecosystems, societies, cultures, family dynamics, flocks of birds, herds of cattle, individual minds, individual bodies, and certainly individual brains — are made up of components (birds in a flock, family members at the  dinner table, plants and animals in an ecosystem) that continue to influence each other. As a result, the relations between them continue to change, which means that the whole system (e.g., the family, the flock, the body, the mind) can continue to alter its form. Change is intrinsic; it doesn’t come from outside the system. Change means change in the interaction patterns, the relationship of the components, not the components themselves.

dinner table, plants and animals in an ecosystem) that continue to influence each other. As a result, the relations between them continue to change, which means that the whole system (e.g., the family, the flock, the body, the mind) can continue to alter its form. Change is intrinsic; it doesn’t come from outside the system. Change means change in the interaction patterns, the relationship of the components, not the components themselves. Your sister makes a caustic remark at the dinner table, then your mother puts down her fork, and then your father gets silent and distant, and then Aunt Jenny starts to criticize your sister. So the shape or form of the family dynamic changes, all by itself, with no particular push from the outside world.

Your sister makes a caustic remark at the dinner table, then your mother puts down her fork, and then your father gets silent and distant, and then Aunt Jenny starts to criticize your sister. So the shape or form of the family dynamic changes, all by itself, with no particular push from the outside world. them personality patterns. Personality patterns (or traits) emerge more and more predictably during childhood and adolescence. (Of course, most people have several and can even be seen switching from one to another — e.g., grumpiness to guilt — as circumstances shift.) These patterns recur, they get reinforced, they set synaptic connections into particular configurations (or recurring synaptic configurations set them, depending on how you look at it), and

them personality patterns. Personality patterns (or traits) emerge more and more predictably during childhood and adolescence. (Of course, most people have several and can even be seen switching from one to another — e.g., grumpiness to guilt — as circumstances shift.) These patterns recur, they get reinforced, they set synaptic connections into particular configurations (or recurring synaptic configurations set them, depending on how you look at it), and  they stabilize. In fact they become incredibly stable. Traits consolidate with development and they perpetuate themselves, becoming “stuck” over the lifespan.

they stabilize. In fact they become incredibly stable. Traits consolidate with development and they perpetuate themselves, becoming “stuck” over the lifespan. That’s why it’s so hard to achieve deep, lasting change through psychotherapy. Hard, but not impossible.

That’s why it’s so hard to achieve deep, lasting change through psychotherapy. Hard, but not impossible. paranoia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, aggressive or antisocial personality style, etc, etc. All those patterns emerge and stabilize over development (even if they get a boost from genetics). They usually become stuck by early adulthood, they cause a lot of misery, and they are hard (but not impossible) to change. Addiction is just another such pattern.

paranoia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, aggressive or antisocial personality style, etc, etc. All those patterns emerge and stabilize over development (even if they get a boost from genetics). They usually become stuck by early adulthood, they cause a lot of misery, and they are hard (but not impossible) to change. Addiction is just another such pattern.