Hi everyone. I haven’t been writing on the blog much lately. My book was released in the UK on July 14th, and that meant shooting off articles for various publications and giving talks and interviews. So I went to London two weeks ago. It’s still there, as colourful and overwhelming as ever. Despite Englands’ majority vote to leave the European union, London is the most multiethnic city imaginable. On ever street you hear a bubbling cauldron of accents and see faces of every colour and shape. What a city!

My trip was fabulous. The first day I was interviewed by The Times, and that night I gave a talk with Johann Hari as my host and interviewer. An interesting man…complex, smart, fun, and a bit darker than expected. The next day, an interview with BBC and another with The Guardian podcast. That night I talked to nearly 400 people — the most positive audience I’ve ever had. Waves of applause and even cheers. Felt like a rock star.

But the most interesting event of my trip was meeting a man named Colin Brewer. If you google him you’ll see that he’s a wild child in British psychiatry circles. Most recently he was villainized by the media for providing

But the most interesting event of my trip was meeting a man named Colin Brewer. If you google him you’ll see that he’s a wild child in British psychiatry circles. Most recently he was villainized by the media for providing  supportive assessments for people seeking assisted suicide in a Swiss clinic. The trouble was that they didn’t have terminal diseases, and that’s a no-no. Was this man a monster? He’d gotten in touch with me by email and came to one of my talks. When he showed up at the foot of the stage, I recognized his face from the internet, and he certainly looked…unusual.

supportive assessments for people seeking assisted suicide in a Swiss clinic. The trouble was that they didn’t have terminal diseases, and that’s a no-no. Was this man a monster? He’d gotten in touch with me by email and came to one of my talks. When he showed up at the foot of the stage, I recognized his face from the internet, and he certainly looked…unusual.

That night at my hotel I googled him more thoroughly and found that the people he’d helped obtain assisted suicide were actually in big trouble. One was 90 years old and in severe, untreatable pain. Another was in his seventies, going blind, another had motor neuron disease, and yet another had Alzheimer’s. It turned out that Colin was motivated by empathy and a firm belief in people’s right to die with dignity. He was no monster.

So I accepted his invitation to come for a visit and arrived at his home a few days later. He lives in a beautiful house in the heart of London. He showed me around the antique-laden interior with evident pride, swelling a bit when I complimented the taste and beauty of his home. And then, equipped with home-made elderberry cordials, we sat and talked.

Colin’s trouble started when he used his own instincts and methods to treat addicts, beginning in the 80s. He prescribed methadone, as did other doctors — no problem. But he would also provide a couple of months’ supply of methadone to people who travelled a great deal and could not renew their prescription daily or weekly. He also prescribed heroin for those who needed it (while this was still legal in Britain) as well as generous supplies of benzos and other drugs for those withdrawing from opiates or alcohol. He even supplied do-it-yourself detox kits to people who could not afford residential care. Another well-intentioned though dissident policy. The press branded his practice a drug supermarket and he was struck off the medical register in 2006.

Colin was indeed a renegade who made up his own rules for dealing with addicts. In fact, like Percy Menzies, who wrote a guest post for this blog several months ago, Colin enthusiastically prescribed naltrexone for opiate addicts as well as disulfiram (Antabuse) for alcoholics. He firmly believed in giving addicts a time-out, a substance-free period for resetting their circuitry — and he brought their families into the act, so that they could help encourage their addicted loved one to stick with the program until they were in safer waters. Far from someone who took his patients’ plights too lightly, he seems to have functioned as a deeply concerned caregiver, who wanted above all to give addicts the freedom to transform their own lives.

We wasted no time discussing whether addiction was a disease or not. We both saw the classic disease model as a dead-end. Rather, we talked about the power of placebos, the extent to which addiction includes placebo-like effects — namely the belief that taking something has particular benefits, when the belief creates the benefits. Colin introduced me to a study showing that even physical withdrawal symptoms can follow sudden termination of a placebo believed to be an addictive drug. Fascinating!

We wasted no time discussing whether addiction was a disease or not. We both saw the classic disease model as a dead-end. Rather, we talked about the power of placebos, the extent to which addiction includes placebo-like effects — namely the belief that taking something has particular benefits, when the belief creates the benefits. Colin introduced me to a study showing that even physical withdrawal symptoms can follow sudden termination of a placebo believed to be an addictive drug. Fascinating!

But the most important idea I left with was Colin’s belief that overcoming addiction is like learning a second language: reframing, retraining, and thus rewiring synaptic networks. I guess I already knew that, but here’s the new punchline. The best way to learn a second language is through total immersion: avoiding going back to your native tongue for some period of time. The reason my Dutch is still so shitty is because I speak English most of the time. That’s sometimes called “controlled use” in addiction parlance.

I’ll end with a quote from an article written by Colin and a colleague. It makes it pretty clear why total abstinence — at least for a time — is so very helpful.

Relapse-prevention is an educational process. Learning to abstain from alcohol or opiates after years of dependence involves selectively suppressing old, maladaptive habits of thought and behaviour and establishing new, adaptive ones. This process resembles foreign language learning…. ‘Immersion’, the most effective foreign language teaching method, discourages students from using their first language…requiring them to use the foreign language instead, however inexpertly.

Colin Brewer & Emmanuel Streel. Substance Abuse, 2003, 24(3) 157-173.

excellent second choice. Judging by his picture and digital presence, I expected a slightly stodgy, soft-spoken academic/scientist type who saw addiction as a disease.

excellent second choice. Judging by his picture and digital presence, I expected a slightly stodgy, soft-spoken academic/scientist type who saw addiction as a disease.

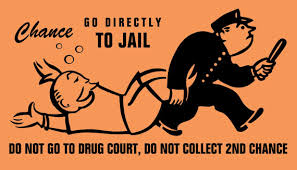

addicts in a country notorious for punishing them? So at 1 pm on a hot October day I pushed through the wooden doors and entered what looked like a stage set from Perry Mason or Law and Order: wooden benches, wooden docks, a couple of flags, a wooden jury box, an expressionless reporter sitting below the judge’s podium, and before long the judge herself, grey haired, robed in black.

addicts in a country notorious for punishing them? So at 1 pm on a hot October day I pushed through the wooden doors and entered what looked like a stage set from Perry Mason or Law and Order: wooden benches, wooden docks, a couple of flags, a wooden jury box, an expressionless reporter sitting below the judge’s podium, and before long the judge herself, grey haired, robed in black. The judge’s sonorous voice called each person by name, and one by one they stood up and walked the short distance to her podium, or stood in place answering questions. But instead of scolding or threatening, the judge spoke to them gently, asked how they were doing. Have you gotten your job situation straightened out? Is your sister still willing to mind the kids while you go to meetings? How’s it going with the stomach problems? You look a lot better than you did last month. Congratulations, Charlene! Three months clean! We knew you could do it! And a chorus of applause would follow. The ones waiting their turn clapped, smiled, and hooted. Charlene gazed at her feet with a grin that looked a lot like pride.

The judge’s sonorous voice called each person by name, and one by one they stood up and walked the short distance to her podium, or stood in place answering questions. But instead of scolding or threatening, the judge spoke to them gently, asked how they were doing. Have you gotten your job situation straightened out? Is your sister still willing to mind the kids while you go to meetings? How’s it going with the stomach problems? You look a lot better than you did last month. Congratulations, Charlene! Three months clean! We knew you could do it! And a chorus of applause would follow. The ones waiting their turn clapped, smiled, and hooted. Charlene gazed at her feet with a grin that looked a lot like pride. Any individual who chooses the drug court path has weighed the alternatives. They can exercise their constitutional rights and take their chances at trial. They can opt for regular probation or request execution of their prison sentences. Or, they can accept a plea negotiation that requires successful completion of a drug court program. If they opt for the latter, they have chosen, to a certain extent, to be coerced to make decisions that will ultimately improve their lives and hopefully steer them away from the courthouse.

Any individual who chooses the drug court path has weighed the alternatives. They can exercise their constitutional rights and take their chances at trial. They can opt for regular probation or request execution of their prison sentences. Or, they can accept a plea negotiation that requires successful completion of a drug court program. If they opt for the latter, they have chosen, to a certain extent, to be coerced to make decisions that will ultimately improve their lives and hopefully steer them away from the courthouse.

prescriptions for methadone, counselling, and a place to hang out for a little while.

prescriptions for methadone, counselling, and a place to hang out for a little while. a staff person present, just being friendly, chatting, offering snacks. The staff consists of two social workers, two MA level psychologists, a criminologist (to help with charges, probation, as so forth), and the doctor, Carl, who wrote the methadone prescriptions. Carl was my host.

a staff person present, just being friendly, chatting, offering snacks. The staff consists of two social workers, two MA level psychologists, a criminologist (to help with charges, probation, as so forth), and the doctor, Carl, who wrote the methadone prescriptions. Carl was my host. (in exchange for used needles) — I mostly sat in a chair next to Carl in an office/interview room, while one client after another came for their methadone script. It was sort of fascinating.

(in exchange for used needles) — I mostly sat in a chair next to Carl in an office/interview room, while one client after another came for their methadone script. It was sort of fascinating. in the chair across from the doc. They often looked defeated and helpless. While some expressed enthusiasm, plans for the future, many looked dreamy or blank. Quite a few had the hunched over posture that expresses shame or remorse. Their eye contact might be sparse and fleeting, looking down a lot — the gaze pattern of people who live with a chronic level of shame or sense of inferiority. A sense of personal failure they’ve grown deeply accustomed to.

in the chair across from the doc. They often looked defeated and helpless. While some expressed enthusiasm, plans for the future, many looked dreamy or blank. Quite a few had the hunched over posture that expresses shame or remorse. Their eye contact might be sparse and fleeting, looking down a lot — the gaze pattern of people who live with a chronic level of shame or sense of inferiority. A sense of personal failure they’ve grown deeply accustomed to.