Hi again. Sorry I’ve been so…absent…lately, but I’ve had a number of ideas I’d like to share with you in the next few weeks. The first involves psychedelics, whose benefits have long remained mysterious. We are finally getting a glimpse of how psychedelics work to improve mental health. And it’s fascinating. So consider this a sequel to the post before last.

I hope you read Eric Nada’s guest post on the promise of psychedelic therapy for helping overcome addiction. Eric reviewed the therapeutic side of psychedelic therapy, and he stressed the importance of working with a knowledgeable and supportive therapist. He emphasized the transformative power of psychedelics, and pointed out that recovery from addiction requires transformation in how we think and feel.

Here I want to focus on how psychedelics act on the nervous system, whether they are taken in a controlled setting with a therapist or on a hilltop in the forest. How do these drugs actually work? Eric began his post remarking on how counter-intuitive it feels to recommend a drug experience for people trying to overcome addiction. But I’ve never felt quite that way. Psychedelics don’t invite us to be cheered up, entertained or numbed. As Eric also concluded, they invite us to open up and change.

When I was a young man, dropping acid and climbing trails through the Berkeley Hills, what I experienced was a massive perspective change, an opportunity to be more attuned to the beauty of the natural world and to my own consciousness. During those years I was also fighting my attraction to opiates and other potentially dangerous drugs, and it took me years to resolve those issues. But LSD and psilocybin (magic mushrooms) were different animals. These substances seemed to offer a way to outgrow the rigid perseverance of my mental habits, my stuckness, my depression and my addiction. If only I could rise to the occasion.

When I was a young man, dropping acid and climbing trails through the Berkeley Hills, what I experienced was a massive perspective change, an opportunity to be more attuned to the beauty of the natural world and to my own consciousness. During those years I was also fighting my attraction to opiates and other potentially dangerous drugs, and it took me years to resolve those issues. But LSD and psilocybin (magic mushrooms) were different animals. These substances seemed to offer a way to outgrow the rigid perseverance of my mental habits, my stuckness, my depression and my addiction. If only I could rise to the occasion.

These days we are inundated with research showing that, indeed, psychedelics can help improve mental health. Anxiety and depression have been shown to be reduced by LSD and psilocybin, in various forms and doses, over dozens of studies. In a study of cancer patients, a single dose of psilocybin “produced immediate, substantial, and sustained improvements in anxiety and depression and led to…improved spiritual wellbeing…” Psilocybin has also been shown to help people quit smoking, and to relieve other addictive spirals. Psychedelics prove to be as effective or more effective than conventional antidepressant drugs for relieving depression, even if taken just once or twice. And there are no side-effects, no measurable addiction potential, and very little risk of ongoing thought disturbance. See this recent review and commentary in Scientific American.

The benefits are no longer speculative. They’re real, and mainstream psychiatry is finally starting to embrace them. But what might be the cause of such improvements? Does anybody know?

Recent research suggests that “opening up” with psychedelics has a very distinct biological basis. Published last month in Neuron, this study shows something almost unbelievable to students of the brain. We’ve been convinced (brain-washed?) for at least 50 years that brain cells don’t regenerate. (By brain  cells I mean the “grey matter,” composed of neurons and their thread-like extensions — dendrites and axons.) They are considered the only cell type in the body that does not reproduce, except for a structure called the hippocampus, and even that shows only limited change beyond early adulthood. The ominous conclusion is, of course, that the brain runs down. Aging seems to reveal a brain that loses its plasticity, its capacity for novelty and change, and even its basic functionality. More to the point, mental problems such as addiction and depression are really hard to fix. Both can be seen as products of neural entrenchment. Maybe you can grow new connections, probably that helps, but you’re stuck with the same complement of grey matter you had at the age of 18. How depressing!

cells I mean the “grey matter,” composed of neurons and their thread-like extensions — dendrites and axons.) They are considered the only cell type in the body that does not reproduce, except for a structure called the hippocampus, and even that shows only limited change beyond early adulthood. The ominous conclusion is, of course, that the brain runs down. Aging seems to reveal a brain that loses its plasticity, its capacity for novelty and change, and even its basic functionality. More to the point, mental problems such as addiction and depression are really hard to fix. Both can be seen as products of neural entrenchment. Maybe you can grow new connections, probably that helps, but you’re stuck with the same complement of grey matter you had at the age of 18. How depressing!

But maybe it’s not that way at all. The Neuron article shows that a single dose of psilocybin produced a rapid and long-lasting increase in the size and density of dendritic spines (the “twigs” that grow out of dendrites) throughout the frontal cortex. The subjects of the study were mice, not humans, but that hardly matters. When it comes to the characteristics of brain cells, like cell growth and regeneration, we mammals are all in the same boat. The researchers reported that the change took place rapidly, with 24 hours, and it was still evident one month later. The extent of growth was approximately 10  percent, a huge number when applied to spontaneous brain change. And — get this — neural transmission (excitatory connection strength) increased measurably, while stress-related behaviour diminished.

percent, a huge number when applied to spontaneous brain change. And — get this — neural transmission (excitatory connection strength) increased measurably, while stress-related behaviour diminished.

So psychedelics appear to actually grow additional grey matter! Note that this is not the same as strengthening or reinforcing synapses, something which occurs during learning but is far less extensive in terms of actual physical change and far more gradual in time. What are the implications? If psychedelics have this kind of firepower, in changing the biological substrate of cognition, then they should be able to induce rapid changes in thinking. In other words, they would be natural habit-breakers! And that’s just what it feels like — that wave of novelty, new paths opening up — to be on psychedelics, whether in a psychiatrist’s office or in the fire-lit circle of an ayahuasca ceremony.

So psychedelics appear to actually grow additional grey matter! Note that this is not the same as strengthening or reinforcing synapses, something which occurs during learning but is far less extensive in terms of actual physical change and far more gradual in time. What are the implications? If psychedelics have this kind of firepower, in changing the biological substrate of cognition, then they should be able to induce rapid changes in thinking. In other words, they would be natural habit-breakers! And that’s just what it feels like — that wave of novelty, new paths opening up — to be on psychedelics, whether in a psychiatrist’s office or in the fire-lit circle of an ayahuasca ceremony.

But when it comes to addiction and other mental-health problems, that’s only half the story. As Eric emphasized in his post, the transformative potential of psychedelics has the greatest traction when it’s guided or

directed by someone knowledgeable, whether therapist or shaman, and when we have a chance to process, practice, and consolidate what it is we are learning. As he says, “the healing benefits of psychedelics are not just produced by the compound itself but through the whole of the experience they inspire.”

directed by someone knowledgeable, whether therapist or shaman, and when we have a chance to process, practice, and consolidate what it is we are learning. As he says, “the healing benefits of psychedelics are not just produced by the compound itself but through the whole of the experience they inspire.”

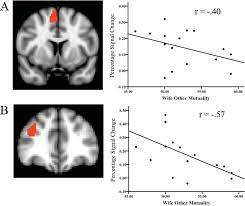

Conclusions? I should clarify that single studies showing remarkable results need replication. That’s next. As well, I’d like to see the present findings jibe with other neurobiological models. In particular, research from a few years back showed that psychedelics increase connectivity across multiple neural regions, in contrast to the usual concentration and boundedness of activation within the default mode network, a region that mediates thoughts about the self (reminiscence, daydreaming, rumination). It would make sense: rapid change in neural maps would be impossible without some kind of “growth booster,” and the rapid, spontaneous improvements reported in the clinical literature point to rapid change.

So, if we take the present results seriously, the conclusion seems pretty straightforward: We use psychotherapy to help people think and understand themselves differently, so that they don’t just respond impulsively or compulsively (as in drug taking) to their needs and fears. It’s been known by various indigenous peoples, for thousands of years, that there are natural chemicals that shake people out of habitual patterns and promote mental change. And now we are starting to learn how this works at the cellular level. Bringing these streams of knowledge together seems an obvious and optimistic route toward improving our mental health…across the board.

P.S. Didn’t your mother tell you that mushrooms are good for you?

Over the last few months there have been numerous reports of a sharp rise in overdose deaths in 2020. Most recently (last month) the National Center for Health Statistics reported

Over the last few months there have been numerous reports of a sharp rise in overdose deaths in 2020. Most recently (last month) the National Center for Health Statistics reported  The experts agree that isolation’s been a major concern. Yet our understanding of the nature of isolation is superficial. Since almost everyone has been on social media this year, madly zooming away the hours, what does it actually mean to be alone, physically, bodily, especially for people living alone, each in their own little box?

The experts agree that isolation’s been a major concern. Yet our understanding of the nature of isolation is superficial. Since almost everyone has been on social media this year, madly zooming away the hours, what does it actually mean to be alone, physically, bodily, especially for people living alone, each in their own little box? The first is Rat Park. Most of you are familiar with Bruce Alexander’s research in the 70s and 80s, memorialized in the addiction world as “Rat Park.” These studies showed that isolated rats (kept alone in their cages) chose to drink water laced with drugs like morphine, while those allowed to socialize, cuddle, and have sex in a park-like (for rats) environment avoided the drug solution and drank plain water instead. There are

The first is Rat Park. Most of you are familiar with Bruce Alexander’s research in the 70s and 80s, memorialized in the addiction world as “Rat Park.” These studies showed that isolated rats (kept alone in their cages) chose to drink water laced with drugs like morphine, while those allowed to socialize, cuddle, and have sex in a park-like (for rats) environment avoided the drug solution and drank plain water instead. There are  thousands of references to Rat Park online (e.g.,

thousands of references to Rat Park online (e.g.,  Subjects inside a brain scanner (fMRI) held hands with either a marital partner, a friend, or a stranger positioned outside the scanner. When exposed to (mild) electrical shocks (psychologists’ favourite way to induce stress) these brain structures showed less activation (they were less “aroused”) when the subject was able to hold hands, even with a stranger. In a review of these studies,

Subjects inside a brain scanner (fMRI) held hands with either a marital partner, a friend, or a stranger positioned outside the scanner. When exposed to (mild) electrical shocks (psychologists’ favourite way to induce stress) these brain structures showed less activation (they were less “aroused”) when the subject was able to hold hands, even with a stranger. In a review of these studies,  I hear my friends and family talking about “Zoom fatigue.” For a reason. Zooming is way way better than no communication at all. But it’s still a partial measure. Texting, Tweeting, Instagram, and other platforms that rely (at least partially) on written characters provide even less of the colour, or tone, or the physicality of mammalian communication. Our brains are full of semantics, words and ideas, and we love exchanging these, exploring and building on them. That’s great. But our brains are part of our bodies, so the sense of comfort and care we get from others comes from an evolutionary heritage tens of millions of years old. A heritage that’s primarily nonverbal.

I hear my friends and family talking about “Zoom fatigue.” For a reason. Zooming is way way better than no communication at all. But it’s still a partial measure. Texting, Tweeting, Instagram, and other platforms that rely (at least partially) on written characters provide even less of the colour, or tone, or the physicality of mammalian communication. Our brains are full of semantics, words and ideas, and we love exchanging these, exploring and building on them. That’s great. But our brains are part of our bodies, so the sense of comfort and care we get from others comes from an evolutionary heritage tens of millions of years old. A heritage that’s primarily nonverbal. Even with all the digital media at our disposal, it’s been a lonely year. And that 30% increase in overdose deaths counts as a reflection of how hard it’s been for many of us. We seem to be starting to conquer Covid-19, at least in the Western world. Let’s keep it up, and let’s spread the wealth. That includes getting vaccinated, so we can protect our families and communities while protecting ourselves. It’s gotta be a group effort, and the group includes humans everywhere. People like us, all over the world, who need to come out of hiding.

Even with all the digital media at our disposal, it’s been a lonely year. And that 30% increase in overdose deaths counts as a reflection of how hard it’s been for many of us. We seem to be starting to conquer Covid-19, at least in the Western world. Let’s keep it up, and let’s spread the wealth. That includes getting vaccinated, so we can protect our families and communities while protecting ourselves. It’s gotta be a group effort, and the group includes humans everywhere. People like us, all over the world, who need to come out of hiding.

I was very nervous the first time I drank ayahuasca. I had been traditionally abstinent for 20 years. Though I suspected that I would stick with my recovery afterward, 12-step philosophy insisted that all mind-altering substances would lead me to the same desperate and re-addicted end. I had recently ended my involvement with that fellowship, trading its emphasis on disease/abstinence for a more intuitive

I was very nervous the first time I drank ayahuasca. I had been traditionally abstinent for 20 years. Though I suspected that I would stick with my recovery afterward, 12-step philosophy insisted that all mind-altering substances would lead me to the same desperate and re-addicted end. I had recently ended my involvement with that fellowship, trading its emphasis on disease/abstinence for a more intuitive  explanation of addiction as a reaction to personal trauma. I had been working on emotional healing from this perspective for a few years and found myself drawn to the stories of others who had used psychedelic medicines for healing and exploration. Still, this path rasied long-held concerns about the pitfalls of drug use.

explanation of addiction as a reaction to personal trauma. I had been working on emotional healing from this perspective for a few years and found myself drawn to the stories of others who had used psychedelic medicines for healing and exploration. Still, this path rasied long-held concerns about the pitfalls of drug use. Far from triggering addictive patterns, my ayahuasca experience was profound, life-altering, and rich in insight. During that first journey, for instance, I saw very clearly how abstinence had “cleared the space” for healing the patterns underlying my addictive drives, but did not provide the healing itself. I also began to see a lifelong pattern of fear that had developed alongside burgeoning feelings of love for significant others in my life. In sharp contrast to “relapse,” it provided a homecoming to my long-standing beliefs about the potential benefits of psychedelics. I have subsequently committed myself to regular work with psychedelics, ever deepening the understanding of my addictive patterns.

Far from triggering addictive patterns, my ayahuasca experience was profound, life-altering, and rich in insight. During that first journey, for instance, I saw very clearly how abstinence had “cleared the space” for healing the patterns underlying my addictive drives, but did not provide the healing itself. I also began to see a lifelong pattern of fear that had developed alongside burgeoning feelings of love for significant others in my life. In sharp contrast to “relapse,” it provided a homecoming to my long-standing beliefs about the potential benefits of psychedelics. I have subsequently committed myself to regular work with psychedelics, ever deepening the understanding of my addictive patterns. addiction. Substances or behaviors that are traditionally habit-forming seem to please or anesthetize the very parts of the psyche that psychedelics directly challenge. Ingesting a psychedelic remains a discipline for me rather than an indulgence. Psychedelics produce not a high but an experience—a journey through consciousness.

addiction. Substances or behaviors that are traditionally habit-forming seem to please or anesthetize the very parts of the psyche that psychedelics directly challenge. Ingesting a psychedelic remains a discipline for me rather than an indulgence. Psychedelics produce not a high but an experience—a journey through consciousness. important aspect of the preparation stage is to establish intention. This is where the participant might formulate specific questions about their addiction. “Why did I develop this pattern? Why am I having trouble changing it? How might I need to change to become a person who doesn’t rely on the mechanics of addiction to function?” This is also the time to highlight any significant history of abuse or trauma that may also be explored during the journey. The idea is that the participant has some understanding of what to expect and what to explore.

important aspect of the preparation stage is to establish intention. This is where the participant might formulate specific questions about their addiction. “Why did I develop this pattern? Why am I having trouble changing it? How might I need to change to become a person who doesn’t rely on the mechanics of addiction to function?” This is also the time to highlight any significant history of abuse or trauma that may also be explored during the journey. The idea is that the participant has some understanding of what to expect and what to explore. Next comes the journey itself. Whoever guides the psychedelic journey should be experienced. They should have extensive knowledge about the compound they administer. They should be able to vet the participant to make sure that they don’t have any psychological or medical issues likely to cause real trouble. And they should be experienced with containing the setting of the experience, able to help the participant navigate any difficult emotional or physiological states encountered

Next comes the journey itself. Whoever guides the psychedelic journey should be experienced. They should have extensive knowledge about the compound they administer. They should be able to vet the participant to make sure that they don’t have any psychological or medical issues likely to cause real trouble. And they should be experienced with containing the setting of the experience, able to help the participant navigate any difficult emotional or physiological states encountered  along the way. The psychedelic journey, itself, produces a radical shift in consciousness. Initial distortions in the visual field soon transform into vast cognitive and emotional reorientation. These shifts drastically alter the way we process our “self”—as if the egoic layers that create the story of who we are become loosened. And as they loosen, we see through them more easily, and rigid patterns that may have escaped conscious detection can become clear. As the journey deepens, the experience often transforms into a dreamlike flow of images, emotions, and physical sensations. During this stage, as the

along the way. The psychedelic journey, itself, produces a radical shift in consciousness. Initial distortions in the visual field soon transform into vast cognitive and emotional reorientation. These shifts drastically alter the way we process our “self”—as if the egoic layers that create the story of who we are become loosened. And as they loosen, we see through them more easily, and rigid patterns that may have escaped conscious detection can become clear. As the journey deepens, the experience often transforms into a dreamlike flow of images, emotions, and physical sensations. During this stage, as the  intensity peaks, insights can seem more intuitive than explicit. Eventually the journey concludes, usually bringing the participant gently back down to the familiar. By the journey’s end, even if parts of it were difficult, the participant is usually left feeling open, unguarded, vulnerable, sated, and shrouded in a feeling of deep resolution.

intensity peaks, insights can seem more intuitive than explicit. Eventually the journey concludes, usually bringing the participant gently back down to the familiar. By the journey’s end, even if parts of it were difficult, the participant is usually left feeling open, unguarded, vulnerable, sated, and shrouded in a feeling of deep resolution. that the process leads to lasting changes after the afterglow has faded. Through integration, epiphany is transformed into practical therapeutic direction aimed at sustained change.

that the process leads to lasting changes after the afterglow has faded. Through integration, epiphany is transformed into practical therapeutic direction aimed at sustained change.

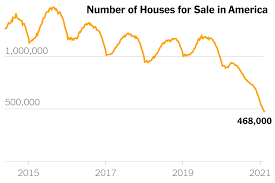

The opioid crisis in the USA gives an excellent example of how the impact of a moral and disease-laden framing of opioids plays out. The combination of an economic crisis, the loss of jobs, increasing inequity, the housing crisis, the increased cost of education and little chance for resolution made people vulnerable to anything that gave them some relief from the pain of their existence, lack of hope and sense of impending failure.

The opioid crisis in the USA gives an excellent example of how the impact of a moral and disease-laden framing of opioids plays out. The combination of an economic crisis, the loss of jobs, increasing inequity, the housing crisis, the increased cost of education and little chance for resolution made people vulnerable to anything that gave them some relief from the pain of their existence, lack of hope and sense of impending failure. Widespread emotional and physical pain combined with direct end-user advertising of opioids and increased prescribing made the rise in opioid use predictable.

Widespread emotional and physical pain combined with direct end-user advertising of opioids and increased prescribing made the rise in opioid use predictable.  spiral out of control. The narrative became a self-fulfilling prophecy. People prescribed opioids started overdosing, by exceeding the correct dose or mixing their opioids with other medications and/or alcohol. Then heroin began to be contaminated with fentanyl. Fentanyl is many times stronger than heroin and was often undetected. People who used heroin began to die from drug poisoning due to fentanyl contamination.

spiral out of control. The narrative became a self-fulfilling prophecy. People prescribed opioids started overdosing, by exceeding the correct dose or mixing their opioids with other medications and/or alcohol. Then heroin began to be contaminated with fentanyl. Fentanyl is many times stronger than heroin and was often undetected. People who used heroin began to die from drug poisoning due to fentanyl contamination. The response, informed by the prohibitionist narrative, was predictable: the aim was to eradicate the drug, cure the disease, get people ‘clean’. The CDC placed restrictions on prescribing opioids. Doctors cut people off from their essential pain

The response, informed by the prohibitionist narrative, was predictable: the aim was to eradicate the drug, cure the disease, get people ‘clean’. The CDC placed restrictions on prescribing opioids. Doctors cut people off from their essential pain  Information about the addictiveness of opioids and the consequences of the disease of addiction dominated the headlines. Predictably, people began to access pharmaceutical drugs from the street. When those ran out, they did the previously unthinkable and started to use heroin. When cut off from opioids, some pain patients

Information about the addictiveness of opioids and the consequences of the disease of addiction dominated the headlines. Predictably, people began to access pharmaceutical drugs from the street. When those ran out, they did the previously unthinkable and started to use heroin. When cut off from opioids, some pain patients  If the response had been value-neutral,

If the response had been value-neutral,  To access networks of people who use drugs, social media and first-responder reports to map contaminated drugs and distribute information about risk areas.

To access networks of people who use drugs, social media and first-responder reports to map contaminated drugs and distribute information about risk areas.

My drug use began with psychedelics. Then came heroin. They’ve always seemed like diametrical opposites. This is where I get my intuitive feel for

My drug use began with psychedelics. Then came heroin. They’ve always seemed like diametrical opposites. This is where I get my intuitive feel for  whether drugs are good or bad. Psychedelics open you up, heroin shuts you down. But I dropped acid roughly 300 times in my late teens and early twenties. I shot heroin about 30-40 times. Why do l assume that heroin is addictive and LSD is pure sunshine?

whether drugs are good or bad. Psychedelics open you up, heroin shuts you down. But I dropped acid roughly 300 times in my late teens and early twenties. I shot heroin about 30-40 times. Why do l assume that heroin is addictive and LSD is pure sunshine? change? [But let me add this: last year I went to a neuroscience conference and learned that

change? [But let me add this: last year I went to a neuroscience conference and learned that  Why do we value control so much? Is control the wedge? Or is harm the crucial marker? Control vs harm and the history of antipsychotics…that increase control and kill the soul. Drugs that harm: don’t they require harm reduction? Or is it happiness, well-being, that’s key? Then why prescribe SSRIs when you could prescribe opiates for emotional pain? If you value control, then get this: drugs are a way to control our thoughts and feelings. Yet self-medication often leads to self-harm. How do we weigh the goodness of drugs when control, well-being, creativity, awareness and harm are all simultaneously changing variables?

Why do we value control so much? Is control the wedge? Or is harm the crucial marker? Control vs harm and the history of antipsychotics…that increase control and kill the soul. Drugs that harm: don’t they require harm reduction? Or is it happiness, well-being, that’s key? Then why prescribe SSRIs when you could prescribe opiates for emotional pain? If you value control, then get this: drugs are a way to control our thoughts and feelings. Yet self-medication often leads to self-harm. How do we weigh the goodness of drugs when control, well-being, creativity, awareness and harm are all simultaneously changing variables? Societal differences — my undergrads at Nijmegen [a rural region of the Netherlands] still see addicts as a different species; in Amsterdam students don’t see it like that. Let’s send Mr Hazelden to an ayahuasca ceremony and see how/whether he evolves.

Societal differences — my undergrads at Nijmegen [a rural region of the Netherlands] still see addicts as a different species; in Amsterdam students don’t see it like that. Let’s send Mr Hazelden to an ayahuasca ceremony and see how/whether he evolves. Why would anyone put ayahuasca in the same category as heroin…isn’t there something intrinsically valuable about perspective change, for its own sake? And what’s the difference

Why would anyone put ayahuasca in the same category as heroin…isn’t there something intrinsically valuable about perspective change, for its own sake? And what’s the difference  between methadone and SSRIs when it comes to allaying depression (yet one is for disgusting addicts and the other is for normal healthy people, like Aunt Mary). But I so disagree with Carl Hart when he says that when your teenage kid wants to try meth your only duty (and your only right) is to educate him/her about safety issues. Are the distinctions between good and bad drugs in the drugs themselves (as we often think reflexively) or in the relation between the drug and the user? We have to really get individual differences. And developmental differences. Binge drinking at 16, not so good…social drinking at age

between methadone and SSRIs when it comes to allaying depression (yet one is for disgusting addicts and the other is for normal healthy people, like Aunt Mary). But I so disagree with Carl Hart when he says that when your teenage kid wants to try meth your only duty (and your only right) is to educate him/her about safety issues. Are the distinctions between good and bad drugs in the drugs themselves (as we often think reflexively) or in the relation between the drug and the user? We have to really get individual differences. And developmental differences. Binge drinking at 16, not so good…social drinking at age  28 can really help people connect. And what I learned from [my good friend and courageous colleague]

28 can really help people connect. And what I learned from [my good friend and courageous colleague]