Since most of us seem to be in vacation mode, myself included, I’m stealing the following passage from Shaun Shelly (with his permission). He in turn took it from Richard Wilmot, author of “American Euphoria: Saying ‘Know’ to Drugs“. The passage compares religious commitments to the commitments made by drug addicts (deals with the devil?). Here I’m printing a shortened version. For the full passage, and for some intriguing reflections on its implications, please see Shaun’s blog. I’m sending you there, partly because this such an unusual idea, but also because Shaun’s blog/newsletter is definitely worth exploring more broadly.

“Today one of the main criteria for a diagnosis of drug addiction/alcoholism is: continuing to consume alcohol or another drug “despite unpleasant or adverse consequences” (DSM). For the Christian martyrs the same criteria would apply. People of that time and place—Rome, 2nd century A.D.—could also say that this new Christianity was like a drug that endangered lives and that being a Christian had all the adverse financial, social, psychological and physical consequences that we now see in the lives of drug addicts and alcoholics. And yet Christians, of all ages, in spite of the consequences, continued to profess their faith… and continued to be eaten by lions.

Obviously there was something to Christianity that prevented the Christian from being abstinent from Christianity. It was something internal… an internal euphoria. It was something that could not be seen but nevertheless was something that was felt… and felt as something awesomely significant. It was something that made all the pain and suffering worthwhile: it was a religious experience.

Likewise, given contemporary social policy, adverse consequences befall those who abuse drugs. They lose the respect of their peers; they violate the expectations of family, friends, and colleagues; they miss out on educational opportunities; they have poor work performance and lose their job. They make harmful decisions. They “burn their bridges”. Their health suffers; they have overdoses, and they die.

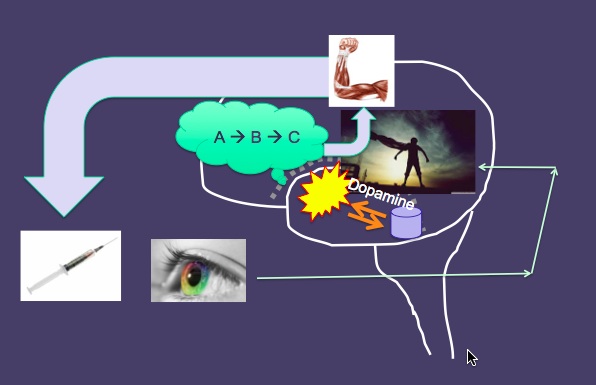

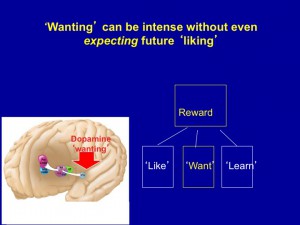

My initial reaction to this quote was one of bemusement more than anything else. Okay, very provocative, but is there a serious point here? Is the comparison between religion and addiction just a high-level play on words? Just a number of descriptors — dedication, single-mindedness, sacrifice, isolation — that make glib connections between two fundamentally different phenomena? That was my hunch. But then I looked  briefly at Wilmot’s book. He makes the case (as do others) that the urge to get high is a natural proclivity, that we all seek what are often called “peak experiences.” In fact, this idea is not much different from the idea of a God gene, as elaborated by Shaun. So not only might we be (at least partially) hard-wired to seek religious meaning, and to seek the sort of peak experiences that come through drugs, but maybe it’s the same urge, channelled in different ways.

briefly at Wilmot’s book. He makes the case (as do others) that the urge to get high is a natural proclivity, that we all seek what are often called “peak experiences.” In fact, this idea is not much different from the idea of a God gene, as elaborated by Shaun. So not only might we be (at least partially) hard-wired to seek religious meaning, and to seek the sort of peak experiences that come through drugs, but maybe it’s the same urge, channelled in different ways.

Then more parallels came to mind. For me, people who are intensely religious are as scary as people who are intensely addicted. Both types are impossible to engage in any meaningful dialogue, they notice only what is of immediate relevance to their particular attraction, and they devalue  others’ rights, opinions, and wellbeing in their pursuit of gratification. And here’s another parallel: religion and addiction look similar to one another at two different stages. Early on, religious zeal and drug attraction are exciting, often creative, and highly fulfilling. But twenty years later, both look like shit. The dogmatic, rigidified, perseverative ramblings of a long-term religious zealot are not much different in tone, quality, or relevance than those of the long-term addict. What was once an exhilarating journey of self-realization has become a bleary-eyed funeral march.

others’ rights, opinions, and wellbeing in their pursuit of gratification. And here’s another parallel: religion and addiction look similar to one another at two different stages. Early on, religious zeal and drug attraction are exciting, often creative, and highly fulfilling. But twenty years later, both look like shit. The dogmatic, rigidified, perseverative ramblings of a long-term religious zealot are not much different in tone, quality, or relevance than those of the long-term addict. What was once an exhilarating journey of self-realization has become a bleary-eyed funeral march.

So, maybe the comparison is more enlightened than I first thought. But make sure you go and visit Shaun’s blog to see what he has to say about it.