Hi you guys! I finally got back here to Holland last week. It’s good to be back. Isabel and I really missed each other and made up for lost time before she picked up the kids and I crashed out. She left for France two days later — for meetings with colleagues. (yeah, right!) The unavoidable reunion scrapping was mild and short-lived. Isabel: how badly was I going to screw up the military precision with which the kids were obeying her every command? Marc: why don’t you just trust me? It’s not like this is the first time. And it was great to see the kids — they are so beautiful to me. Julian’s teeth have almost filled up his mouth again, the better to argue with, my dear. Ruben is still a wild man when he kicks a ball and a lamb when you ask for help. And they liked the presents I finally remembered to get, last minute, at an airport store that sells useless things to guilt-ridden parents.

So about the last three weeks: where do I start? Maybe with the culture shock of being back in the USA. Of course North America is where I come from, but the Marriott in Boston boasted new heights of excess. There were fully 50 TV screens in the one and only restaurant. Two banks of them, entirely circling the seating area. The drinks had so much ice in them, my mouth felt loaded with novocaine. And every server seemed compelled to smile brilliantly, ecstatically, whenever making eye contact. They would say things like “And how are we doing today?” And I wanted to say “I have no idea how you’re doing. But where can I get some of whatever you’re on?” Or was this just Pavlovian conditioning of some network of facial muscles in response to the smell of a tip? What a weird country. But I must admit that some of the most interesting people in the world happen to live there.

After spending a week at that Mind and Life conference/retreat, and driving around New England with my dear daughter, I finally found myself in Boston for the main act — the “pre-meeting” for the meeting with the Dalai Lama (who they call His Holiness: I’ll just call him HH in this post.) I’m sitting there at a long table, it’s 9 AM Monday, and I hadn’t slept very well. A true case of “opening night nerves.” Today we were supposed to run through all the talks and I was slated to go first. They wanted to start off with a real-life portrayal of addiction. Just in case HH and/or the couple of hundred monks and scholars who would be there in the room, sitting behind the inner circle of us, or the 5,000 or so camped down the road in front of a jumbotron, or the tens of thousands who’d watch us live on the net — just in case some of them didn’t know an addict or weren’t one themselves — seems rather unlikely.

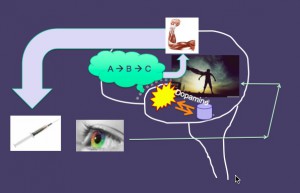

My nerves start to mellow while I’m giving my talk. People seem engaged. Here’s one of the slides I like best. I wish I knew how to include the animation, but you can imagine these different stages of the cycle popping up consecutively.

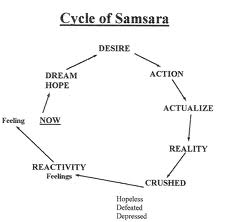

But then I get to this slide…

This image was created by John Harper. Used with thanks.

…and I’m pointing out how the cycle of brain states involved in addiction fits so nicely on the cycle of states in the Buddhist wheel of suffering, or whatever it’s called, when this guy thunders out from the far end of the table: “That’s not Buddhism! I don’t know where you got that but it’s not Buddhism.” And I sagely reply: “Well I looked through about 200 Google images and this was the only one in English.”

But what raised my pulse the most was the presence of some very renowned brain scientists. There was Richard Davidson, across the table. He’s the guy who first put Buddhist monks — long-term meditators — in the scanner, to see what brain regions light up when you’re not thinking about pizza. And Nora Volkow was present on Skype from Washington. She’ll be coming to Dharamsala in the flesh, so that should be interesting. She seemed relatively tame, at least on the screen, but when the “disease vs. learning” issue came up, she got right into it. Spunky for sure, but also willing to listen to other opinions.

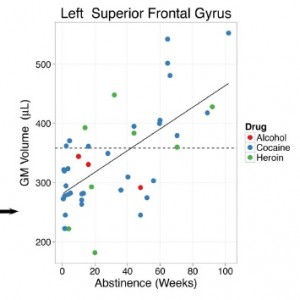

And who should be sitting beside me but Kent Berridge. If you’ve been following this blog or read my book, you know I worship the ground he walks on. His theory of addiction is unique and it’s pretty much universally acknowledged to be in first place. He divides “wanting” from “liking” and describes them as independent neural systems that work together in normal learning. In addiction, however, the “wanting” network, which is fueled by dopamine, gets highly sensitized to drug (or alcohol, food, or whatever) cues — so addiction is a runaway of process of “wanting” and has little to do with “liking”.

So this brilliant guy is sitting next to me. And he seems so…human. Humble, shy, self-effacing. But most obviously a kind and compassionate man. How do I know? When he, Davidson and I were walking to lunch, Kent continued to drop back a pace from walking shoulder-to-shoulder with Davidson so as to keep me in the loop, so that I was with them rather than following them. That’s a kind of social sensitivity you don’t often get from strangers, or from anyone, and I immediately liked him for that if nothing else.

On my other side is a guy name Jinpa — a very poised and polished Tibetan who apparently serves as the interpreter for HH in these dialogues. HH speaks English fairly well, I’m told, but misses some of the technical bits. So there’s Jinpa, a Harvard grad, or was it Oxford? Definitely in his element with this crew. And then comes Joan Halifax, a famous Western Buddhist scholar who apparently spends her days helping people in the process of dying. No kidding. That’s what she does. And then Vibeke Frank from Denmark, who looks at addiction as a social construction. In other words, you’re not really an addict unless you’re defined that way by your culture. Next, at the end of the table, sits this grandiose philosopher dude who told me my slide was wrong. And then, on the other side of the table, Sarah Bowen, who heads up the Mindfulness-based Relapse Prevention (MBRP) camp — a very cool approach to addiction treatment that uses mindfulness/meditation to get through to the other side of craving episodes. And someone named Wendy Farley who talks about some ancient body known as Christian contemplatives. I thought her stuff was terrific — certainly a face of Christianity that emphasizes forgiveness rather than sin, and that sees “desire” as a good thing, until it gets overly focused on filling yourself up. Then some Mind & Life staffers. Mostly people in their thirties, but including one very seasoned Buddhist scholar, who later sat me down and explained what was wrong with my slide. She showed me how incredibly complex the Buddhist cycle actually was. What I thought (and I guess I wasn’t alone) was a cycle of consecutive states actually looked more like a 12-sided sphere, with all twelve sides linking to one another, so that it ends up looking something like this!!

I told her I’d dropped out of Hebrew school when things got too complicated, so maybe she should just give me the dumbed down version. I think she finally did.

Now you’ve got the setting and the characters. Next comes the content. I’ve taken care of a few pressing matters, so I can put up another post in a day or two. There’s lots more to tell.