Happy New Year! I’m sure we’re all hoping that this year brings renewed optimism, through the creative, caring, and sensible use of all that’s available in this era of rapid change. In that spirit, I discuss my thoughts about “good drugs” and share my recent experience of DMT.

My twin boys are now thirteen, so they are approaching the age at which they’re likely to be exposed to drugs of all sorts. Like most parents, Isabel and I are concerned. We’re trying to find the right preparation and the right logic to steer them away from drug experiences that will likely be harmful. What can we say that provides guidance, not prohibition? Should we try to persuade the boys to avoid all drugs? Not a very useful strategy, says Carl Hart, and I agree. Not only would they probably dismiss our counsel and ignore our views on drugs completely — after all, we’d simply be displaying our biases. But on this point I follow Sam Harris. Somewhere in his book, Waking Up — A Guide to Spirituality without Religion, he says something like this: (don’t quote me — this is from memory) I hope my kids will never tell me they’ve experimented with meth or heroin. But I also hope they won’t tell me that they’ve avoided the psychedelics with equal fervor. I like Sam Harris. I like his approach to mindfulness, consciousness, and living with awareness. I’ve also just begun his guided meditation app. I highly recommend it.

There are so many kinds of drugs we could talk about with our kids, and the legal system provides almost no help when it comes to sorting them according to potential risk. After all, alcohol and tobacco are the most hazardous of substances, statistically, and they’re both legal. My intuition is to divide non-medical (“recreational”?) drugs into three categories:

- Those you should never ever touch: methamphetamine, heroin, crack cocaine. Besides the risk of overdose with heroin and psychosis or stroke with psychostimulants, all three drugs are highly addictive. I want to scare my kids appropriately, using my own past experiences for all they’re worth.

- Those you’d be best to avoid but probably won’t harm you if you explore cautiously, use occasionally, and learn about the risks: nonaddictive party drugs like ecstasy (MDMA) and ketamine.

- Those that really are okay if used appropriately: including alcohol, an aspect of human social rituals for roughly ten thousand years…but more interestingly, the psychedelics. If you are not vulnerable to psychosis or other severe mental health issues, then psychedelics can be beneficial in the pursuit of self-actualization or just exploring unique aspects of mind, consciousness, and reality. Of course, tread cautiously. Don’t go into these waters without guidance, companionship, and some degree of knowledge. But these drug experiences are among the adventures available to our age.

The psychedelics were epitomized by LSD in my generation. Psilocybin (magic mushrooms) and mescaline were also quite common. For young people in the current era, psilocybin is still frequently used. More recent additions include ayahuasca and other forms of DMT. These DMT compounds might be most  attractive (and challenging!) to today’s intrepid psychonaut. And by the way, psychonaut is a real word; it refers to the exploration of altered states, including but not limited to “mind-altering” drugs.

attractive (and challenging!) to today’s intrepid psychonaut. And by the way, psychonaut is a real word; it refers to the exploration of altered states, including but not limited to “mind-altering” drugs.

There’s much to say about the ritualistic use of DMT by aboriginal cultures, the shamanic element, the social contexts considered helpful and supportive, and the limited research conducted so far. This Wikipedia page is a good start. It’s also important to note that psilocybin and MDMA are now being used by licensed psychiatrists to help their patients overcome anxiety, depression, addiction, and other unfortunate habits of mind (see Michael Pollan).

There’s much to say about the ritualistic use of DMT by aboriginal cultures, the shamanic element, the social contexts considered helpful and supportive, and the limited research conducted so far. This Wikipedia page is a good start. It’s also important to note that psilocybin and MDMA are now being used by licensed psychiatrists to help their patients overcome anxiety, depression, addiction, and other unfortunate habits of mind (see Michael Pollan).

But you can read all this on the net. Let me tell you about my own recent experience.

I wrote about my first ayahuasca trip in this blog a few years ago. After five or six ceremonies, I decided that’s enough. The insights were profound, the hallucinations penetrating and beautiful, but running to the toilet every half-hour got old.

More recently, I heard an intriguing description of a trip with The Toad. Bufo Alvarius secretes a substance (5-MeO-DMT) that is dried and then smoked in a glass pipe. The toad is not killed but respectfully released after its DMT is collected. The trip is supposed to be rapid (5-25 minutes) and intense. Efficient, right? So I joined a friend in the UK for my introduction. We had a shaman usher us into this strange world, a short, tough-talking Brit from northern England who’d spent a prolonged period in the Sonoran Desert learning about Bufo from the natives who used it. John was a no-nonsense guy radiating expertise as well as compassion. His Tibetan bowls, drums, and feathers were ready to accompany us into, through, and out of the hallucinatory state.

More recently, I heard an intriguing description of a trip with The Toad. Bufo Alvarius secretes a substance (5-MeO-DMT) that is dried and then smoked in a glass pipe. The toad is not killed but respectfully released after its DMT is collected. The trip is supposed to be rapid (5-25 minutes) and intense. Efficient, right? So I joined a friend in the UK for my introduction. We had a shaman usher us into this strange world, a short, tough-talking Brit from northern England who’d spent a prolonged period in the Sonoran Desert learning about Bufo from the natives who used it. John was a no-nonsense guy radiating expertise as well as compassion. His Tibetan bowls, drums, and feathers were ready to accompany us into, through, and out of the hallucinatory state.

We met in a church hall, chilly and unadorned. But it was enough. John and his helper arranged two padded bed-rolls which you sat against at first and then lay back on when the DMT hit your nervous system. I’d been feeling  afraid of this moment for days. My friend spoke about “ego death” — leaving your personality behind, essentially dying as an individual and becoming connected with the rest of the universe intimately but without control. Sure, I was scared. “Ego death” has the word “death” in it.

afraid of this moment for days. My friend spoke about “ego death” — leaving your personality behind, essentially dying as an individual and becoming connected with the rest of the universe intimately but without control. Sure, I was scared. “Ego death” has the word “death” in it.

For some reason, my fear disappeared the day of the event. I felt ready. By mutual consent, I went first. I was doused in tobacco smoke (an American native ritual) and cleansed of badness with the swoosh of a feather. I sat on the bed-roll. John ordered me to exhale completely, then held the stem of a glass pipe to my lips and lit it from below. Inhale, he said. More, more, keep going! And I did, until it felt like my  lungs would burst. And then the room began to dissolve before my eyes. All of its features simply faded to colourful outlines and then…nothing at all. Strong hands helped me to lie back. Close your eyes now — I could still hear his voice. But I wasn’t in the room anymore.

lungs would burst. And then the room began to dissolve before my eyes. All of its features simply faded to colourful outlines and then…nothing at all. Strong hands helped me to lie back. Close your eyes now — I could still hear his voice. But I wasn’t in the room anymore.

Where was I? Of course it’s nearly impossible to describe. Something like a limitless pink space full of fluctuating colours and…feelings. It was a space of pure emotion. I felt great joy, gratitude that the universe would welcome me so easily. “Marc” meant nothing anymore, but I could still record my experience consciously. And right in the middle of all that joy there was a sort of black hole, called “anguish.” It held the greatest depths of despair, and I recognized a direct trajectory that’s extended through my life, from childhood to the present. The message, if I can call it that, was simple: this is the part of my experience that I thought I could not bear, that has always terrified me. Yet here it is, and it’s just…a feeling. Just loss. This truth seemed incredibly important, and when I came back to the room, smiling up at my companions, groggy and googly-eyed, it was still with me, undiminished.

I don’t want to get into deep speculation as to what I learned from Bufo. But I’m grateful for the awareness it lent me. For weeks I began my day with a simple sense of acceptance. It seemed that nothing in my emotional space needed to be hidden, or deleted, or modified. It seemed (and often still does) that my sense of reality has no preordained limits, and there is something that can be perceived, something caring and supportive, in the fabric of consciousness itself.

Perhaps in the coming year, the coming years, drugs like DMT will help us discard our preoccupation with our selves and trade our individuality for a connectedness that includes our fellow humans and the planet we share.

Regardless, I learned a lot from them. For example, I learned that zebrafish larvae (baby fish that look like seahorses) like opioids. These little guys will swim up near the surface of their tank — which is intrinsically aversive to

Regardless, I learned a lot from them. For example, I learned that zebrafish larvae (baby fish that look like seahorses) like opioids. These little guys will swim up near the surface of their tank — which is intrinsically aversive to  them — to get Vicodan. Yes, Vicodan…through their feeding tube. And I learned that fruit flies will endure 120 volts of electricity to get a nip of alcohol. Yet they won’t do it for sugar. Crayfish get stoked on cocaine and race around recklessly with their claws outstretched. Like, seriously! I also learned that dopamine is the neurochemical by

them — to get Vicodan. Yes, Vicodan…through their feeding tube. And I learned that fruit flies will endure 120 volts of electricity to get a nip of alcohol. Yet they won’t do it for sugar. Crayfish get stoked on cocaine and race around recklessly with their claws outstretched. Like, seriously! I also learned that dopamine is the neurochemical by  which lower animals identify and pursue rewards. They may even get a dopamine burst when they acquire drug rewards. I could give you more details, but in sum, it’s pretty simple: opioids and psychostimulants cause physiological changes that we interpret as “good” or “rewarding” — “we” being animals from flies and fish to humans. And we do this using the same neurotransmitters — dopamine and serotonin — across species that evolved hundreds of millions of years apart! It’s no accident that heroin and meth are the most addictive drugs we know of. We’re in good company.

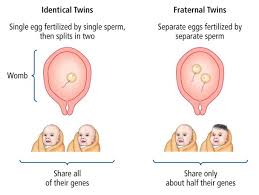

which lower animals identify and pursue rewards. They may even get a dopamine burst when they acquire drug rewards. I could give you more details, but in sum, it’s pretty simple: opioids and psychostimulants cause physiological changes that we interpret as “good” or “rewarding” — “we” being animals from flies and fish to humans. And we do this using the same neurotransmitters — dopamine and serotonin — across species that evolved hundreds of millions of years apart! It’s no accident that heroin and meth are the most addictive drugs we know of. We’re in good company. ages, than others. So they and their identical twins (the basis for computing genetic effects) are more likely to become addicted. An introverted or anxious disposition also predicts addiction, for obvious reasons. And, as Maia Szalavitz says about herself, I think I score pretty high on both of these (seemingly opposite) traits. So…my odds started off a little higher than average.

ages, than others. So they and their identical twins (the basis for computing genetic effects) are more likely to become addicted. An introverted or anxious disposition also predicts addiction, for obvious reasons. And, as Maia Szalavitz says about herself, I think I score pretty high on both of these (seemingly opposite) traits. So…my odds started off a little higher than average. But here’s what I learned about genetics. Over the history of genetic research, labs could only look at gene-outcome effects one by one. That’s not the way genetics operates. With the huge explosion of computer technology in the last few years, scientists can now look at complex interaction effects. These include, not only genes, but the parts of the DNA that regulate networks of genes. Now things get complicated. I already knew that trauma or early adversity can “set” changes in motion which last a lifetime — called “epigenetic” effects. For example, punitive parenting can set your amygdala on high alert for the rest of your life — i.e., induce trait anxiety. These changes take place at the DNA level, but — and it’s a huge “but” — they are driven by environmental impacts. So, again, environment wins out over inheritance. What I didn’t get until last week is the complexity of the interactions between these environmental impacts and the genes we inherit.

But here’s what I learned about genetics. Over the history of genetic research, labs could only look at gene-outcome effects one by one. That’s not the way genetics operates. With the huge explosion of computer technology in the last few years, scientists can now look at complex interaction effects. These include, not only genes, but the parts of the DNA that regulate networks of genes. Now things get complicated. I already knew that trauma or early adversity can “set” changes in motion which last a lifetime — called “epigenetic” effects. For example, punitive parenting can set your amygdala on high alert for the rest of your life — i.e., induce trait anxiety. These changes take place at the DNA level, but — and it’s a huge “but” — they are driven by environmental impacts. So, again, environment wins out over inheritance. What I didn’t get until last week is the complexity of the interactions between these environmental impacts and the genes we inherit. One of the scientists speaking at the conference,

One of the scientists speaking at the conference,

dedicated scientist at the reception, isolation in Sweden and isolation in New Jersey are entirely different things. The gradations in environmental impact are close to infinite. He disagreed, said it’s a matter of time, but I guess the jury’s still out.

dedicated scientist at the reception, isolation in Sweden and isolation in New Jersey are entirely different things. The gradations in environmental impact are close to infinite. He disagreed, said it’s a matter of time, but I guess the jury’s still out.

Doctors are taught from year 1 Medicine (if not before): First, do no harm. And yet, in treating addicted individuals, doctors often do more harm than good — by obstructing or totally derailing the recovery process. That should never happen! I want to show you what I mean by telling you part 2 of Sally’s story —

Doctors are taught from year 1 Medicine (if not before): First, do no harm. And yet, in treating addicted individuals, doctors often do more harm than good — by obstructing or totally derailing the recovery process. That should never happen! I want to show you what I mean by telling you part 2 of Sally’s story —  life on the street. And she tended to obsess about her next dose for too much of her day. She wanted to have done with it. Yet, withdrawing from heroin had been so grueling — it still terrified her. So the solution was obviously to taper gradually.

life on the street. And she tended to obsess about her next dose for too much of her day. She wanted to have done with it. Yet, withdrawing from heroin had been so grueling — it still terrified her. So the solution was obviously to taper gradually. pressing me: let’s go down another two tablets this week. I don’t think I need my second morning dose. She started to skip doses…and that meant she had a reservoir of spares, just in case. She was tailoring it, shaping it, doing it. She was the boss.

pressing me: let’s go down another two tablets this week. I don’t think I need my second morning dose. She started to skip doses…and that meant she had a reservoir of spares, just in case. She was tailoring it, shaping it, doing it. She was the boss. through the very end of her taper and possible withdrawal symptoms — not even 15 or 20 tabs. Valium is very addictive, you know. But that was okay: they’d taper together. She’d come to the office every week — not an easy trek for a mother of three small kids, but it was important for him to see her, to monitor her. And she would reduce her intake by one tablet — 30 mg — at a time, he insisted. But she had to agree that every time she reduced her dose, she’d have to maintain the new level. She couldn’t go back up. Not even for a particularly bad day. He knew what was best for her. Did she agree? Did she have a choice? If she didn’t agree he’d stop her prescription, and then she’d be in danger of paracetamol poisoning again, unless she went back to heroin.

through the very end of her taper and possible withdrawal symptoms — not even 15 or 20 tabs. Valium is very addictive, you know. But that was okay: they’d taper together. She’d come to the office every week — not an easy trek for a mother of three small kids, but it was important for him to see her, to monitor her. And she would reduce her intake by one tablet — 30 mg — at a time, he insisted. But she had to agree that every time she reduced her dose, she’d have to maintain the new level. She couldn’t go back up. Not even for a particularly bad day. He knew what was best for her. Did she agree? Did she have a choice? If she didn’t agree he’d stop her prescription, and then she’d be in danger of paracetamol poisoning again, unless she went back to heroin. I saw Sally next a few days after that visit. Her energy was gone. Her smile was sad and cynical. She’d gone back up to her previous high dose, including the paracetamol torpedoes, because…because it wasn’t her recovery anymore. That’s how she put it. And it was none of his damn business and she didn’t like his rules and she didn’t like him. But the threat of a sudden withdrawal trumped all that. That was the power he wielded, and he knew it.

I saw Sally next a few days after that visit. Her energy was gone. Her smile was sad and cynical. She’d gone back up to her previous high dose, including the paracetamol torpedoes, because…because it wasn’t her recovery anymore. That’s how she put it. And it was none of his damn business and she didn’t like his rules and she didn’t like him. But the threat of a sudden withdrawal trumped all that. That was the power he wielded, and he knew it.

Since moving to the Netherlands nine years ago, this was my third — yes third — spinal surgery. You wouldn’t know it. I’m limber, I can do anything from a 2-hour Tai Chi class to a half-day of zip-lining. But my spine has this uncool tendency to grow too much bone, called stenosis. The bone squeezes my nerves, and then I get pain. For example, leg pain. Sciatica.

Since moving to the Netherlands nine years ago, this was my third — yes third — spinal surgery. You wouldn’t know it. I’m limber, I can do anything from a 2-hour Tai Chi class to a half-day of zip-lining. But my spine has this uncool tendency to grow too much bone, called stenosis. The bone squeezes my nerves, and then I get pain. For example, leg pain. Sciatica. The MRI confirmed what my nerves were telling me (about my bones). Not enough room in this town for both of us. So a surgery was planned and I asked my doc for some oxycodone — lots of it — or an equivalent. I’m not fond of pain.

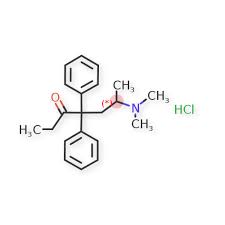

The MRI confirmed what my nerves were telling me (about my bones). Not enough room in this town for both of us. So a surgery was planned and I asked my doc for some oxycodone — lots of it — or an equivalent. I’m not fond of pain. defense. (That’s why your nervous system manufactures buckets of them.) But we’d be foolish to overlook the addictive properties of any drug that makes us feel better — and that part is psychological. In the case of opioids it’s physiological too. (See my debate with Maia Szalavitz in the comment section, last post.) Hence the notorious feedback effect: what you take to reduce your suffering leads to more suffering. Super bad planning!

defense. (That’s why your nervous system manufactures buckets of them.) But we’d be foolish to overlook the addictive properties of any drug that makes us feel better — and that part is psychological. In the case of opioids it’s physiological too. (See my debate with Maia Szalavitz in the comment section, last post.) Hence the notorious feedback effect: what you take to reduce your suffering leads to more suffering. Super bad planning! at once. They’re not being driven by guidelines shaped by profit and reinforced by fears of being disciplined or sued. So…decisions about what to take and how long to take it are shared between doctor and patient. As they should be.

at once. They’re not being driven by guidelines shaped by profit and reinforced by fears of being disciplined or sued. So…decisions about what to take and how long to take it are shared between doctor and patient. As they should be.

How did Sally get into heroin? When she was 14, a teacher at the children’s home began touching her genitals. She wasn’t angry at the time, she says, but her perception of adults changed entirely from that point on. A couple of months

How did Sally get into heroin? When she was 14, a teacher at the children’s home began touching her genitals. She wasn’t angry at the time, she says, but her perception of adults changed entirely from that point on. A couple of months  later, a math teacher–she remembers him as being very old, with bad teeth–started making advances. This time, she threw a chair at him. She got kicked out of school for her troubles, and that’s when she got to know Mike, who introduced her to heroin.

later, a math teacher–she remembers him as being very old, with bad teeth–started making advances. This time, she threw a chair at him. She got kicked out of school for her troubles, and that’s when she got to know Mike, who introduced her to heroin. tom-boy ways. Sally liked looking for bugs under rocks rather than dressing nicely. That’s just Sally being Sally, the family concluded. And she became an outsider in her own home. By adolescence she’d often end up swearing at her mom, sniffing glue and hanging out with the wrong kids on the corner.

tom-boy ways. Sally liked looking for bugs under rocks rather than dressing nicely. That’s just Sally being Sally, the family concluded. And she became an outsider in her own home. By adolescence she’d often end up swearing at her mom, sniffing glue and hanging out with the wrong kids on the corner. He started off as her friend, someone to love her and listen to her. Then he became her pimp, demanding that she go out and find money to score more dope. Her young body was all that stood between his well-being and withdrawal symptoms. He’d beat her up if she refused–broken ribs, a couple of teeth knocked out– except when he got worried about damaging the merchandise.

He started off as her friend, someone to love her and listen to her. Then he became her pimp, demanding that she go out and find money to score more dope. Her young body was all that stood between his well-being and withdrawal symptoms. He’d beat her up if she refused–broken ribs, a couple of teeth knocked out– except when he got worried about damaging the merchandise. once, sitting at a street corner, head lolling back, almost unrecognizable because she was so thin. But she just kept driving. That’s just Sally being Sally. Skeletal and bruised, waiting for a man degraded enough to look past the bruises for 20 minutes of warmth. That’s who she became. Until she was rescued by a man who got her off dope, as long as she’d never look at another man again.

once, sitting at a street corner, head lolling back, almost unrecognizable because she was so thin. But she just kept driving. That’s just Sally being Sally. Skeletal and bruised, waiting for a man degraded enough to look past the bruises for 20 minutes of warmth. That’s who she became. Until she was rescued by a man who got her off dope, as long as she’d never look at another man again. The real story of Sally’s addiction is so diametrically opposite anything resembling a disease. The web of social, economic, and familial factors, the absence of a social safety net, the play-it-safe inclination of child-welfare services that weren’t interested in the child’s version of events. That’s where the problem arose. So where was it to be solved? In a doctor’s office? In a methadone clinic?

The real story of Sally’s addiction is so diametrically opposite anything resembling a disease. The web of social, economic, and familial factors, the absence of a social safety net, the play-it-safe inclination of child-welfare services that weren’t interested in the child’s version of events. That’s where the problem arose. So where was it to be solved? In a doctor’s office? In a methadone clinic?