Hi people. It’s been awhile. I left off with some brief descriptions of the Dialogue and summaries/links for two great talks. Now I want to tell you something about Nora Volkow’s presentation and, more interestingly, the chat we had afterward.

I have been running to keep up with myself for at least a month, and now I’m finally able to slow down, relax, and post something. I’m in Toronto for a week. I came to give a couple of talks, see family and friends, and just hang out. Isabel  and I have literally been playing tag team to accommodate travel and children. I’m away, she’s at home with the kids, she’s away, I’m at home with the kids. We’ve spent only 4 days in the same place for over a month! She was returning from the US last Thursday, the day I left for Toronto. We were in the Arnhem train station at the same time but texting, trying to meet up, when we must have walked right past each other. By the time we connected, I was in the train and she was getting in a taxi. Funny and a bit sad.

and I have literally been playing tag team to accommodate travel and children. I’m away, she’s at home with the kids, she’s away, I’m at home with the kids. We’ve spent only 4 days in the same place for over a month! She was returning from the US last Thursday, the day I left for Toronto. We were in the Arnhem train station at the same time but texting, trying to meet up, when we must have walked right past each other. By the time we connected, I was in the train and she was getting in a taxi. Funny and a bit sad.

Ok, Nora Volkow, head of NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse). She’s often been a voice in my head when I’ve argued against the disease model of addiction in my writing and blogging. Why? Because she is one of the most eloquent and knowledgeable proponents of the disease approach, she is a powerful force in the worlds of research funding and policy-making, and because she’s a highly respected researcher. Who better to argue with, at least in my head?

She gave her presentation on day 3 of the dialogue. Here’s the link to the talk itself and here’s Shaun’s summary. She focused mostly on the blunting of dopamine reactivity in the brains of addicts, resulting both in the reduced “rewardingness” of drugs and a reduced capacity for cognitive control. A lot of people liked her talk. She’s a great speaker: passionate but clear, with well-defined logical connections between data and interpretation. His Holiness looked like he enjoyed her presence, and Richie Davidson seemed enraptured. I liked her talk too. However…

She gave her presentation on day 3 of the dialogue. Here’s the link to the talk itself and here’s Shaun’s summary. She focused mostly on the blunting of dopamine reactivity in the brains of addicts, resulting both in the reduced “rewardingness” of drugs and a reduced capacity for cognitive control. A lot of people liked her talk. She’s a great speaker: passionate but clear, with well-defined logical connections between data and interpretation. His Holiness looked like he enjoyed her presence, and Richie Davidson seemed enraptured. I liked her talk too. However…

I was listening for a rethink or even a mild qualification of her well-know contention that addiction is a chronic brain disease. But it wasn’t there. She continues to see addiction as resulting from the “damage” caused by repeated drug use. And she uses that word “damage” insistently, even though the measures available for assessing brain changes generally show them to be reversible (e.g., grey matter density changes). Two things have bothered me about this position for quite some time: (1) it makes drug addiction a completely separate animal from all other addictions (e.g., gambling, sex, food), despite evidence of overlapping or identical brain changes; (2) it places the cause of addiction squarely in the molecular action of the substance itself, something Nora emphasized repeatedly, ignoring the crucial lessons of Rat Park and subsequent research on environmental determinants.

Ok, so she’s Nora Volkow, she’s a pillar of the medical establishment (NIH), and she finds it valid and convenient to classify dysfunction as disease. So what’s my problem? Maybe it was in reaction to a comment she made later that day that my blood boiled over (gently of course). During a discussion period she proposed to debate whether addiction is “a disease of the brain or a disease of the mind.” She was so sure of herself. I looked around the circle of fellow presenters and organizers. Doesn’t anyone else question whether it’s even a disease?

So during the final hour of the final session (Day 5, morning, following Sarah Bowen’s talk) I picked up the microphone and waved it around for a good 20 minutes before I got my chance. The clock was ticking toward the end of the session. Only a few minutes left. I waved the microphone a bit more frantically, and Richie Davidson, the moderator of that session, gave me the last few minutes before lunch. I was nervous. I’d been aware of my heart pounding most unprofessionally. I didn’t want to defy the great Nora or piss off my newfound colleagues. The proceedings so far had been quite lovey dovey, almost devoid of serious academic debate. I didn’t want to breach that policy. Yet it seemed cowardly to sit back. I thought of you guys and some of the heated comments you’ve made about the disease model — how the logic never quite spoke to you, or how it left you feeling boxed and helpless.

So during the final hour of the final session (Day 5, morning, following Sarah Bowen’s talk) I picked up the microphone and waved it around for a good 20 minutes before I got my chance. The clock was ticking toward the end of the session. Only a few minutes left. I waved the microphone a bit more frantically, and Richie Davidson, the moderator of that session, gave me the last few minutes before lunch. I was nervous. I’d been aware of my heart pounding most unprofessionally. I didn’t want to defy the great Nora or piss off my newfound colleagues. The proceedings so far had been quite lovey dovey, almost devoid of serious academic debate. I didn’t want to breach that policy. Yet it seemed cowardly to sit back. I thought of you guys and some of the heated comments you’ve made about the disease model — how the logic never quite spoke to you, or how it left you feeling boxed and helpless.

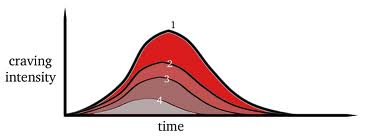

So I said my bit. (Most of you have heard it before.) Maybe addiction isn’t a disease at all…given that recovery seems to derive from self-reflection, concentration, and effortful revision of one’s perceptions and goals, given that brain change is essential to all learning processes, and given that radical synaptic restructuring is the rule at developmental transitions (e.g., adolescence). And if addiction isn’t a disease, then perhaps it is best treated, not by the medical profession, but by programs of the type that Sarah Bowen had just described so beautifully — based on mindfulness and other methods of revamping our responses to our own cravings.

Nora did not look particularly pleased with my comment. But Sarah did. Richie I couldn’t read. Then, as people got up and milled around, preparing for lunch, I sampled the vibes as much as I could. And concluded that some were glad to have an opposing perspective on the table, a few were not, and most didn’t much care.

Since Nora was among the last to leave the room, I walked over to her and asked her what she thought of my comment. Surely she’s been confronted with opposition to the disease model. And sure enough she had a string of arguments already loaded and ready to fire. Here they are:

- Not all diseases show up as major bodily disruptions. Some are far more subtle.

- Calling something a disease doesn’t mean that it can’t be helped by psychosocial interventions. Even cancer recovery can be aided by mindfulness (to improve the mood and the self-care practices of patients).

- Drugs damage brain tissue. For example, cocaine has been shown to directly damage the brains of rats, and by extension, probably humans, as does alcohol.

- But beyond the damage issue, when something doesn’t work the way it should, we call it a disease. That’s how the word is used — that’s how language works.

- Calling addiction a disease mitigates massive volumes of stigma and guilt, and it deflects blame from those who’ve fallen prey to addiction.

- Arguing definitions is futile. Call it anything you want. The point is to get help for people who need it. And if we don’t treat addiction as a disease, it won’t be treated at all.

I could argue with most of these points, I thought. For one thing, I just don’t believe that most drugs cause brain damage, except in cases of extreme quantities and other critical factors, such as the impact of vitamin deficiency in Korsakoff’s syndrome, impure or toxic concoctions, overdose, etc, etc. And if you don’t believe me, look at the articulate prose of someone like David Carr (the New York Times journalist who smoked a ton of crack and drank a ton of booze over many years, then wrote The Night of the Gun). And sex addiction, gambling, and the other behavioral addictions aren’t likely to cause brain damage either. And in a country where the government is not in the business of helping people in dire need of help (including the poor, the sick, the old, the young, single parents, victims of accidents, abused women and children…the list goes on), perhaps the disease definition is the best avenue for getting help for low-functioning addicts. But that’s politics, not science, and it’s politics that fits one country, not the world at large.

As (my now friend) Kent Berridge tried to convince me later, we shouldn’t have to accept one definition or the other — both might be accurate for different individuals, stages, or circumstances. Yet the working (sub)title of my current book is “…why addiction is not a disease.” So I’ve got quite a stake in the argument. I don’t want to get bogged down in a useless war of words, and I certainly don’t want to spend my efforts trying to dismiss a “straw man” — a contrived version of my intellectual opponent that’s easy to refute because it’s exaggerated or fraudulent. And Nora wasn’t interested in further debate just now. That was clear — and lunch was calling.

But I’ll end by saying that, if my scientific beefs about the disease model turn out to be valid, something fundamental has to change in the way we label, understand, and treat addiction. Because it’s not just a war of words. After reading thousands of comments and emails from ex- or recovering addicts, I’m convinced that calling addiction a disease is not only inaccurate; it’s harmful. It’s harmful because it replaces one stigma with another. People don’t often boast about their incurable diseases — they are nothing to be proud of. And a sense of responsibility probably doesn’t do much to combat most diseases, but it’s a crucial part of the arsenal for combating addiction. To put it differently, those who have fought addiction and won — really won — hardly see themselves as lacking responsibility. Nor are they keen to walk on egg-shells for the rest of their lives, lest the latent virus erupt once more. For them, for us, there are more satisfying ways to define ourselves than “My name is Joe and I’m an alcoholic.” Most of the recovered addicts I’ve talked to would rather see themselves, not as in remission, but as free. Maybe better than ever.

talked of being a young gay man from a traditional Chinese family. He was rejected by his family and peers with such vehemence that he ended up wandering around Toronto like a stray puppy, looking for anyone he could follow home. Not surprisingly, sex was part of that equation, and, apparently not uncommonly, so was crystal meth. Clean needles and condoms were the furthest thing from his mind. Until he got sick. Now, HIV-positive and who knows what else, he stood there, quavering, clearing his throat, telling this group of strangers all about his shameful deeds. And everybody’s heart went out to him. There wasn’t one person in the room who didn’t wish they’d gotten to him first, not to put a halt to his experimentation but to help him survive it. When he told us he’d been clean for almost four years, the room erupted in waves of applause. But it didn’t seem he’d be a poster-child for HR or anything else for very much longer.

talked of being a young gay man from a traditional Chinese family. He was rejected by his family and peers with such vehemence that he ended up wandering around Toronto like a stray puppy, looking for anyone he could follow home. Not surprisingly, sex was part of that equation, and, apparently not uncommonly, so was crystal meth. Clean needles and condoms were the furthest thing from his mind. Until he got sick. Now, HIV-positive and who knows what else, he stood there, quavering, clearing his throat, telling this group of strangers all about his shameful deeds. And everybody’s heart went out to him. There wasn’t one person in the room who didn’t wish they’d gotten to him first, not to put a halt to his experimentation but to help him survive it. When he told us he’d been clean for almost four years, the room erupted in waves of applause. But it didn’t seem he’d be a poster-child for HR or anything else for very much longer. From that moment it was clear to me that harm reduction and abstinence were not opposing goals. And I was sold. I don’t think you can fully buy into harm reduction until you stare straight into the totality of harm.

From that moment it was clear to me that harm reduction and abstinence were not opposing goals. And I was sold. I don’t think you can fully buy into harm reduction until you stare straight into the totality of harm. I never stopped wondering whether this was precisely the right approach. But I became convinced it was a lot better than nothing for seriously down-and-out users. If you met them with restrictions, rules, shame or disapproval, they would simply disappear. Disappearing was one thing they were particularly good at. That and destroying themselves.

I never stopped wondering whether this was precisely the right approach. But I became convinced it was a lot better than nothing for seriously down-and-out users. If you met them with restrictions, rules, shame or disapproval, they would simply disappear. Disappearing was one thing they were particularly good at. That and destroying themselves.