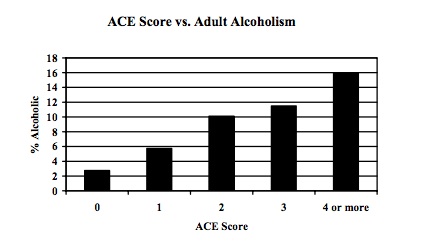

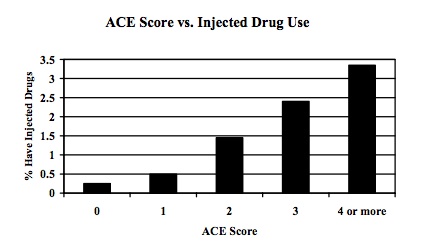

Last post I reviewed a study showing powerful correlations between traumatic experiences in childhood and adolescence and addictive behaviours in adulthood. Although several readers found significant holes in the research, the study maintains a fair bit of respectability, and besides, if we look at our own lives, I think we often see clear connections between personal hardships and addiction. This sort of “anecdotal” evidence, subjective and biased though it may be, is often the strongest reason, deep down, for accepting (or rejecting) the self-medication model.

The self-medication model portrays addictive behaviours as attempts to diminish the feelings of anxiety, loss, shame, and loneliness left in trauma’s wake. For me, the connection is too obvious for words. I was lonely, depressed, and constantly on the lookout for personal attacks while at boarding school as a teenager. Within a year of leaving, I had shot enough heroin to end up unconscious in a bathtub, appearing to my friends to be dead. I don’t for a moment doubt the connection between these episodes of my life. And I say that, not as a scientist, but as a regular person, trying to make sense of my life.

I recently spoke with a reader who has serious problems with alcohol, but only when things go wrong in her personal life. Eleven months of the year she has no craving, no attraction to alcohol. She doesn’t even have to be on guard because there’s no urge to get drunk. However, when her (now, thankfully, ex) husband became verbally and physically abusive, when her custody of her child was being challenged, when she had to go and live with her parents because the matrimonial home was a torture chamber….those were the times she drank to excess. Emphasis on excess. How can you be an “addict” only when things get tough, and then become a non-addict when life goes back to normal? The disease model simply can’t explain that sort of pattern, whereas the self-medication model predicts it. Threat and anxiety lead her to take alcohol, which makes it easier for her to bear.

But there are problems with the self-medication model that need to be addressed.

First, although trauma may lead to addiction, it isn’t necessary — addiction does not have to be preceded by trauma. Some people fall into addiction without any evident history of trauma. Instead, other factors, such as peer pressure or simple exposure, might be sufficient. Check out the video recommended by Steve Matthews as a prime example.

Second, we know that self-medication doesn’t work very well. The things we take or do to diminish bad feelings actually increase them in the long run, or even in the not-so-long run. Maybe we’re not very good doctors. We prescribe for ourselves treatments that do more harm than good. Or they work for a little while — a month, a week, an evening — and then we get hit by the after-effects. Our dopamine-powered beam of attention cares only about the immediate, not the long run. Pretty short-sighted for a doctor.

These iatrogenic (more harm than good) effects don’t actually conflict with the theme of self-medication. If you’ve ever tried prescription antidepressants (SSRIs) or painkillers for legitimate reasons, you know that many medications produce iatrogenic effects. These drugs often lead to dependency and an uncomfortable period of withdrawal. But the fact that self-medication often makes matters worse leads us to another question: Is the trauma we are “medicating” produced by the medication itself? That’s about as vicious a circle as I can imagine, and it challenges the very idea that trauma causes addiction — rather than the other way around, as pointed out recently by Conor (in a comment following my last post).

So let’s imagine a causal story that goes completely opposite to that proposed by the self-medication model.

As I noted above, some people start down the road to addiction without having lived through serious trauma. But even given a certain amount of trauma in childhood/adolescence, one’s PTSD or depression might be under control. When I first tried heroin, I wasn’t terrifically happy but I wasn’t in great psychic pain, relatively speaking. Then I stumbled on a substance that made me feel terrifically happy. Enter the choice model: I want to do that again, because it’s more valuable to me than any alternative. After a while, the substance or activity is a presence in one’s life. And that presence takes on increasing value: it’s sorely missed when it’s gone. Now the source of my anxiety wasn’t so much my historical injuries (e.g., my mother’s depression, my stint at boarding school). Rather it was my present fear of going without dope, and wanting it badly, and not being able to stop thinking about it. Now we’ve got at least two of the most common outcomes of trauma – loss and anxiety – both caused by present drug-taking rather than historical events.

Then along comes outcome number 3: shame. The loss of self-control – whether due to dirty underwear at age 4 or slavering desperation to get high at age 24 – is contemptible. That’s how others see it, so that’s how we see it. The result is shame, and guess what? Shame is one of the most common residues of trauma.

From an article in The Fix, on 25 Sept 2011, comes the following:

Of all the ACEs (adverse childhood experiences) that muck up one’s life, “’the one with the slight edge, by 15% over the others, was chronic recurrent humiliation, what we termed as emotional abuse,’ says Dr. Vincent Felitti, one of the directors of the study.” Shame is one of the few emotions that is directly, viscerally painful. Now, combine the loss you feel after running out or stopping, with the anxiety you get from craving what you can’t seem to get, with the shame that comes from your lack of self-control, and you’ve got a feast of negative emotions. The need for self-medication is now at its peak — indicating that the addiction itself is the trauma.

The vicious circle — connecting addiction to psychic pain leading to further addiction – may well be the causal engine we’ve been searching for. But self-medication is only one part of this cycle: it doesn’t work all that well as an explanation that connects traumatic life events to a special, intrinsic need for self-soothing. What it really shows, as suggested by Nik, is that, for some period of time, we believe that there’s one thing in the world that can make us feel better.

Of the three models of addiction, self-medication works best for me. As long as we acknowledge that trauma is an ongoing progression with its roots in our childhood but its branches still growing, still advancing, sometimes wildly, out of control, with each addictive act.