On January 28 I started a series of posts reviewing promising psychotherapeutic approaches to addiction. I managed to cover a few, though with stops and starts — mostly due to Covid hassles and anxieties. So today I’m continuing the series with a post on Internal Family Systems (IFS). I wanted to understand it better before trying to explain it, and I think I finally do.

For years my online therapy with people in addiction has relied on my early training in psychodynamic therapy, dobs of mindfulness-meditation, what I’ve picked up from emotion-focused psychotherapy, ACT, Gestalt and other gems, plus my own personal experience of addiction. Add to that 30 years studying developmental psychology with a focus on emotion regulation, and what I’ve learned about the brain processes that underlie addiction and drug use. All of this came together in my own hybrid style of therapy. And it usually helped. Yet there were people I couldn’t help at all. There were brick walls and false leads and levels of trauma, chaos and heartbreak that left me gaping, and left my clients no further ahead. I knew I needed more training.

Internal Family Systems has been around since the 80s, and more and more people are becoming aware of it. It’s not easy, primarily because its premises go against the grain of mainstream psychology. Instead of trying to fuse the parts of the person into one coherent whole, IFS allows the parts to remain parts, it sort of honours them, so that you can get to know them, listen to them, understand them, and eventually take care of them. With respect to addiction, you never hear “you must stop.”

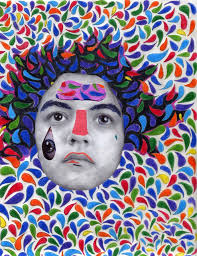

What are these parts? Maybe you’ve thought of them as voices, or selves, or subpersonalities — it doesn’t matter. They appear as habitual perceptions or expectations with distinct emotional loadings (e.g., anxiety, anger, longing) — and they can be intrusive in the background or they can seem to take over.

What are these parts? Maybe you’ve thought of them as voices, or selves, or subpersonalities — it doesn’t matter. They appear as habitual perceptions or expectations with distinct emotional loadings (e.g., anxiety, anger, longing) — and they can be intrusive in the background or they can seem to take over.

In working with addiction, the parts are not hard to find. Addicts often identify at least two. One is the “addict self” who just wants to get high (or to binge or have sex). That part is powerful, it  overtakes the system, it has no regard for tomorrow, and it’s very difficult to resist. In AA, it’s said to be doing push-ups in the parking lot. In psychology jargon, it’s called compulsion. NIDA calls it a diseased brain. But I don’t find any of these concepts at all helpful. From a neuroscience perspective, I can point to the part of the brain that “does” compulsion — the dorsolateral striatum — but all that’s really doing is putting a habit into play. And as we know, addictive urges are all about habit. So what happens if we consider this to be a part of a person that is young, energetic, one-track minded, and determined to overcome negative emotion in the only way it knows how? When you think about it that way, it’s hard to negate it or to hate it.

overtakes the system, it has no regard for tomorrow, and it’s very difficult to resist. In AA, it’s said to be doing push-ups in the parking lot. In psychology jargon, it’s called compulsion. NIDA calls it a diseased brain. But I don’t find any of these concepts at all helpful. From a neuroscience perspective, I can point to the part of the brain that “does” compulsion — the dorsolateral striatum — but all that’s really doing is putting a habit into play. And as we know, addictive urges are all about habit. So what happens if we consider this to be a part of a person that is young, energetic, one-track minded, and determined to overcome negative emotion in the only way it knows how? When you think about it that way, it’s hard to negate it or to hate it.

The other part addicts often identify is the voice that gives you royal shit for doing it, thinking about it, planning it, having done it (drinking, drugs, gambling, whatever) last night or every night  for the last week or the last month. We often call this the internal critic, and its specialty is self-blame and self-contempt. So what happens if we see this part as a younger version of ourselves, who learned to be our caretaker or disciplinarian? You better be good! Don’t you dare goof up again! You’re going to be in real trouble if you do that!! Once we see this part as trying to help keep us out of trouble, it’s hard to feel alienated from it or even victimized by it. Instead, IFS asks us to open a dialogue with this part. For example: You come out whenever I’m likely to do something “bad” (like call my dealer), don’t you — I guess that’s been a full-time job lately. But then you get so upset with me that I get seriously depressed, and then I just want to get high all the more. Let’s try reducing the pressure a bit.

for the last week or the last month. We often call this the internal critic, and its specialty is self-blame and self-contempt. So what happens if we see this part as a younger version of ourselves, who learned to be our caretaker or disciplinarian? You better be good! Don’t you dare goof up again! You’re going to be in real trouble if you do that!! Once we see this part as trying to help keep us out of trouble, it’s hard to feel alienated from it or even victimized by it. Instead, IFS asks us to open a dialogue with this part. For example: You come out whenever I’m likely to do something “bad” (like call my dealer), don’t you — I guess that’s been a full-time job lately. But then you get so upset with me that I get seriously depressed, and then I just want to get high all the more. Let’s try reducing the pressure a bit.

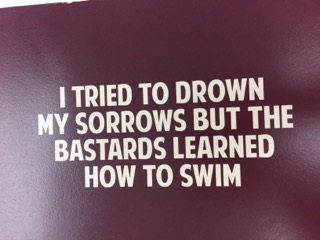

And there lies the problem for most addicts. (I use that word for convenience, as you know.) The critical voice and the “let’s get high” voice activate and augment each other. Endlessly. In IFS, both these parts are called “protectors” because their job is to take care of you. Neither one is evil. They just have radically different styles. The critical voice or “manager” thinks only of the future. The “getting high” distractor voice thinks only of the present. These two parts branched off and solidified, earlier in development, because you needed them. Or so it seemed. How  many times a day do you suppose the average 6-year-old thinks about NOT getting in trouble? How many times did you do bad shit anyway? The trouble now is that those two parts are so busy trying to shut each other down that you can’t get anywhere. Neither part will stop doing what it’s doing. It all seems so hopeless.

many times a day do you suppose the average 6-year-old thinks about NOT getting in trouble? How many times did you do bad shit anyway? The trouble now is that those two parts are so busy trying to shut each other down that you can’t get anywhere. Neither part will stop doing what it’s doing. It all seems so hopeless.

IFS recognizes a third class of parts called “exiles”. These are (usually) the really young parts that have experienced trauma or abuse of one kind or another. They are terrified. They’ve been hurt or shamed beyond their capacity to heal. We normally can’t or don’t want to re-experience that hurt, so we keep it buried. Hence the term “exile” (what psychoanalysts call the unconscious). But we don’t bury all of that pain…the hurt rises up inside us when we feel desperate, alone, misunderstood, or threatened. Addiction itself can trigger these feelings! And that’s exactly when the distractor — the “I need to get high” voice — gets activated. I can take care of this awful feeling, it says. Right now! Which of course triggers the manager part: Don’t you dare! You promised. Then the savage back-and-forth between these parts pushes the exiles further down, hides them even more, and douses them with more shame and fear…in case there wasn’t enough already.

Having practiced IFS as a therapist now for several months, I am sold on its efficiency and its power. (I’ve even begun as a client, myself, with an IFS therapist. What better way to learn the ropes…not to mention some timely self-improvement.) My clients “get it” almost at once. I don’t have to sell them on the rather esoteric imagery and jargon. They just take a look inside and say, Um yeah, that’s pretty much what’s happening. And then they start to change.

Having practiced IFS as a therapist now for several months, I am sold on its efficiency and its power. (I’ve even begun as a client, myself, with an IFS therapist. What better way to learn the ropes…not to mention some timely self-improvement.) My clients “get it” almost at once. I don’t have to sell them on the rather esoteric imagery and jargon. They just take a look inside and say, Um yeah, that’s pretty much what’s happening. And then they start to change.

This is just a bare-bones intro. Let me end by saying that the goal of IFS is to let your Self (they spell it with a capital S) start to take care of your parts — appreciate them, comfort them, ask them to turn down the volume, to step back a bit. And reassure them that you — the present whole you, the Self, the calm centre that you may find in meditation — are going to take care of things, and take care of them — so they can begin to relax.

It’s pretty remarkable to feel that start to happen. You don’t feel so desperate. And all those layers of hopelessness begin to lighten and float away.

Obviously the impact of lockdown and social distancing has been serious for many of my readers, and I’ve struggled to think of what I could share that might help. Finally I think I’ve got something to say. Even as the world closes down around you, you have to stay open!

Obviously the impact of lockdown and social distancing has been serious for many of my readers, and I’ve struggled to think of what I could share that might help. Finally I think I’ve got something to say. Even as the world closes down around you, you have to stay open! soothes you and defines you. And then, as time goes by, you connect with people more shallowly, you connect with fewer people, you connect with fewer people who might actually love you — family, friends, lovers. That’s the outer garment of addiction: the thinning, the contraction, of the social world. And it parallels the “contraction” of available neural networks in the addict’s brain.

soothes you and defines you. And then, as time goes by, you connect with people more shallowly, you connect with fewer people, you connect with fewer people who might actually love you — family, friends, lovers. That’s the outer garment of addiction: the thinning, the contraction, of the social world. And it parallels the “contraction” of available neural networks in the addict’s brain. So living through this pandemic, here’s the main problem. The impact of social distancing on many people is increased loneliness, greater contraction of the social world, an accelerated plunge into being by yourself. For people with addictions, that’s the opposite of what they need most, the opposite of what they need in order to forget about getting high, at least for awhile.

So living through this pandemic, here’s the main problem. The impact of social distancing on many people is increased loneliness, greater contraction of the social world, an accelerated plunge into being by yourself. For people with addictions, that’s the opposite of what they need most, the opposite of what they need in order to forget about getting high, at least for awhile. Maybe it’s obvious, but it’s also what I’ve been told by my psychotherapy clients, especially those who haven’t quite found their way back to a drug-free (or drug-reduced) existence. The four walls feel more like concrete barriers than dividers in a lively hive. The doors and windows start to feel like relics of an existence that’s no longer possible. You can’t go out, you can’t mix, you can’t meet up, except online. And that’s just not quite the same. All you’ve got left is your addiction…or so it seems.

Maybe it’s obvious, but it’s also what I’ve been told by my psychotherapy clients, especially those who haven’t quite found their way back to a drug-free (or drug-reduced) existence. The four walls feel more like concrete barriers than dividers in a lively hive. The doors and windows start to feel like relics of an existence that’s no longer possible. You can’t go out, you can’t mix, you can’t meet up, except online. And that’s just not quite the same. All you’ve got left is your addiction…or so it seems. okay, but they’re kids. They’re not there for you. You’re there for them. So, infused in your isolation are the toxic currents of stress, not

okay, but they’re kids. They’re not there for you. You’re there for them. So, infused in your isolation are the toxic currents of stress, not  only boredom but frustration and anger and a sense of inadequacy. All of which derive from the situation, but it feels like they derive from you, from your own shortcomings. There you are, trapped inside your bunker, with heightened demands and anxieties that would be hard enough to deal with if you were free to get out and mix with other parents and relatives and the world at large. Forced captivity with junior cell-mates is nothing like being free to wander and connect.

only boredom but frustration and anger and a sense of inadequacy. All of which derive from the situation, but it feels like they derive from you, from your own shortcomings. There you are, trapped inside your bunker, with heightened demands and anxieties that would be hard enough to deal with if you were free to get out and mix with other parents and relatives and the world at large. Forced captivity with junior cell-mates is nothing like being free to wander and connect. And it’s springtime! (at least in the northern hemisphere) The bushes and trees are budding and leafing like crazy, the flowers are coming out. My mood improves about 300% after I’ve walked around for awhile. And when you get home, call or zoom someone you care about. Ask

And it’s springtime! (at least in the northern hemisphere) The bushes and trees are budding and leafing like crazy, the flowers are coming out. My mood improves about 300% after I’ve walked around for awhile. And when you get home, call or zoom someone you care about. Ask  about them. They’ll ask about you too. It’s easy to imagine that our isolation is some kind of penance for imagined wrongdoings. It’s not! The world is still full of people. And you still have an instinctive need to connect with them, in whatever way you can.

about them. They’ll ask about you too. It’s easy to imagine that our isolation is some kind of penance for imagined wrongdoings. It’s not! The world is still full of people. And you still have an instinctive need to connect with them, in whatever way you can.

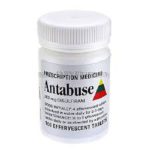

Last post I suggested that we can attend to (rather than reject) our cravings and pursue integration rather than abstinence. Today, a contrasting view: Colin Brewer, a renowned and controversial addiction doctor, explains how Antabuse and naltrexone can free us from endless ruminations while new habits take root and grow.

Last post I suggested that we can attend to (rather than reject) our cravings and pursue integration rather than abstinence. Today, a contrasting view: Colin Brewer, a renowned and controversial addiction doctor, explains how Antabuse and naltrexone can free us from endless ruminations while new habits take root and grow. abstinence before they change their self-image from “I’m an addict/in recovery” to “I used to be an addict but now I’m different.” Keeping these treatment-resistant addicts drug-free — or at least free of their main problem drug — for 18-24 months is made a lot easier by the consistent use of drugs that deter their use. Disulfiram (Antabuse) deters alcohol use by the prospect of an unpleasant physical reaction and naltrexone deters opiate use by the prospect of an unpleasant psychological reaction.

abstinence before they change their self-image from “I’m an addict/in recovery” to “I used to be an addict but now I’m different.” Keeping these treatment-resistant addicts drug-free — or at least free of their main problem drug — for 18-24 months is made a lot easier by the consistent use of drugs that deter their use. Disulfiram (Antabuse) deters alcohol use by the prospect of an unpleasant physical reaction and naltrexone deters opiate use by the prospect of an unpleasant psychological reaction. under supervision (and thus stayed dry) for at least 20 months,

under supervision (and thus stayed dry) for at least 20 months,  most of them stayed dry without disulfiram (and mostly without other treatment) for the next 7 years of follow-up. In other words, by simple daily practice and repetition, their alcohol-using habits had been abandoned and replaced by habits that didn’t include alcohol. We don’t yet have similar long-term studies of naltrexone for opiate dependence but with naltrexone implants that can last six-months or even a year

most of them stayed dry without disulfiram (and mostly without other treatment) for the next 7 years of follow-up. In other words, by simple daily practice and repetition, their alcohol-using habits had been abandoned and replaced by habits that didn’t include alcohol. We don’t yet have similar long-term studies of naltrexone for opiate dependence but with naltrexone implants that can last six-months or even a year  in existence or in development, we soon will have. I predict that the longer-acting the implant, the better the results will be because fewer decisions to continue treatment (compared with monthly Vivitrol injections) need to be made in the crucial first few months.

in existence or in development, we soon will have. I predict that the longer-acting the implant, the better the results will be because fewer decisions to continue treatment (compared with monthly Vivitrol injections) need to be made in the crucial first few months.

You probably know the parts better than you think. My addict self comes out of nowhere and roars into life. She’s incredibly determined, so I end up giving in before I even know it. Twelve-steppers say she’s doing push-ups in the parking lot. That part seems so evidently not-self, and yet it obviously is a part of

You probably know the parts better than you think. My addict self comes out of nowhere and roars into life. She’s incredibly determined, so I end up giving in before I even know it. Twelve-steppers say she’s doing push-ups in the parking lot. That part seems so evidently not-self, and yet it obviously is a part of  the self. Or: I give myself such shit the morning after. You’re just a fucking loser, addict, drunk. You don’t deserve sympathy. You don’t even deserve to be alive! Again, that voice comes at us, so it feels like not-self, yet it obviously is a part of the self as well. Who else could it be?

the self. Or: I give myself such shit the morning after. You’re just a fucking loser, addict, drunk. You don’t deserve sympathy. You don’t even deserve to be alive! Again, that voice comes at us, so it feels like not-self, yet it obviously is a part of the self as well. Who else could it be? reserved an Airbnb, cleared my calendar. And then the coronavirus came along and dashed my plans, as it has obliterated plans, wishes, normalcy, for so many of us. So I won’t write about IFS today. I don’t understand it well enough yet. But I already practice a kind of psychotherapy that recognizes “parts” — so I feel an intuitive connection with this approach, and my reading on IFS continues to flesh it out. More on IFS later.

reserved an Airbnb, cleared my calendar. And then the coronavirus came along and dashed my plans, as it has obliterated plans, wishes, normalcy, for so many of us. So I won’t write about IFS today. I don’t understand it well enough yet. But I already practice a kind of psychotherapy that recognizes “parts” — so I feel an intuitive connection with this approach, and my reading on IFS continues to flesh it out. More on IFS later. how you feel. It can leave you staring into an existential void, facing an abyss of emptiness and meaninglessness. So, abstinence very often leads to “relapse.” We know this story well, and it provides a (false) rationale for defining addiction as a chronic disease.

how you feel. It can leave you staring into an existential void, facing an abyss of emptiness and meaninglessness. So, abstinence very often leads to “relapse.” We know this story well, and it provides a (false) rationale for defining addiction as a chronic disease. that part and, instead of turning our back on it, telling it “No, never again!” what if we were to embrace that part, listen to it, and comfort it. What if, instead of banishing the needy part, we were to get to know it, maybe even get to love it, so that it doesn’t have to feel so walled off, shunned and hated.

that part and, instead of turning our back on it, telling it “No, never again!” what if we were to embrace that part, listen to it, and comfort it. What if, instead of banishing the needy part, we were to get to know it, maybe even get to love it, so that it doesn’t have to feel so walled off, shunned and hated. The logic is simple: as long as we wall off this part of us, it not only continues to exist, it gets more desperate and determined. Now it has to weaponize and force its way through. In psychodynamic parlance, the more you suppress a powerful urge, the stronger (or more devious) it becomes.

The logic is simple: as long as we wall off this part of us, it not only continues to exist, it gets more desperate and determined. Now it has to weaponize and force its way through. In psychodynamic parlance, the more you suppress a powerful urge, the stronger (or more devious) it becomes. Little kids crave what they can’t have, and the cookie jar doesn’t lose its appeal by being placed out of reach. So we give the little kid something else to eat, maybe a piece of fruit or cheese (think methadone). And/or we create a bridge to the treasured outcome. We say, you can certainly have a cookie, in fact two cookies, when it’s dessert time. That’s after dinner, at 6:30. Do you think you can wait that long? Let me help you. Let’s get busy doing something else.

Little kids crave what they can’t have, and the cookie jar doesn’t lose its appeal by being placed out of reach. So we give the little kid something else to eat, maybe a piece of fruit or cheese (think methadone). And/or we create a bridge to the treasured outcome. We say, you can certainly have a cookie, in fact two cookies, when it’s dessert time. That’s after dinner, at 6:30. Do you think you can wait that long? Let me help you. Let’s get busy doing something else. of integration you foster in yourself. The craving part is young and wild, defiant, and very much alone. But it’s a part of you! Finding out where it comes from — in your growing up years, in your efforts to control troubling emotions, in

of integration you foster in yourself. The craving part is young and wild, defiant, and very much alone. But it’s a part of you! Finding out where it comes from — in your growing up years, in your efforts to control troubling emotions, in  your battles against depression and anxiety — allows it to relax and connect with the rest of you. This opens the door to self-acceptance and self-love, which often seem so elusive in addiction.

your battles against depression and anxiety — allows it to relax and connect with the rest of you. This opens the door to self-acceptance and self-love, which often seem so elusive in addiction. People, please please click on

People, please please click on

How should we address ourselves with compassion and love when in fact, according to the Buddhists (and according to neuroscience), selves don’t actually exist. The self is an illusion, says the Buddha, and I have a hunch he’s right. What has any of this to do with addiction and recovery? You’ll see.

How should we address ourselves with compassion and love when in fact, according to the Buddhists (and according to neuroscience), selves don’t actually exist. The self is an illusion, says the Buddha, and I have a hunch he’s right. What has any of this to do with addiction and recovery? You’ll see. LIGHT IS RED. (This can be done either on a bike or on your feet. It works best when it’s raining, which is pretty much always.) Halfway or more across, gaze back at the people still huddled on the sidewalk. Look at their faces, twisted in the agony of, not only indecision but true existential paralysis, a sense of doubt (that extends back to the Big Bang and covers everything up to this morning). They see you crossing, they want to cross, they wish they could cross, but the light’s red. Their expressions reveal horror, confusion, contempt, envy, and most of all shock. Because there it is: the fundamental impossible-ness of life — the paradox that can’t be mended, the incompatibility of two totally logical, obvious, unarguable truths. The epitome of unsolvability. (see above) And you know, some of them will cross and others won’t, and regardless, in both sets of people, you can detect the early signs of mental breakdown. I’m no Buddhist scholar but some of the stuff I’ve read, like Robert Wright’s “

LIGHT IS RED. (This can be done either on a bike or on your feet. It works best when it’s raining, which is pretty much always.) Halfway or more across, gaze back at the people still huddled on the sidewalk. Look at their faces, twisted in the agony of, not only indecision but true existential paralysis, a sense of doubt (that extends back to the Big Bang and covers everything up to this morning). They see you crossing, they want to cross, they wish they could cross, but the light’s red. Their expressions reveal horror, confusion, contempt, envy, and most of all shock. Because there it is: the fundamental impossible-ness of life — the paradox that can’t be mended, the incompatibility of two totally logical, obvious, unarguable truths. The epitome of unsolvability. (see above) And you know, some of them will cross and others won’t, and regardless, in both sets of people, you can detect the early signs of mental breakdown. I’m no Buddhist scholar but some of the stuff I’ve read, like Robert Wright’s “ the stuff going on outside you is all just stuff going on. (I realize this is a truly inadequate summary of the main tenets of Buddhism. I’m no Buddhist scholar, as mentioned, so why pretend.) True, consciousness seems to illuminate the stuff going on inside you and around you in a particular way, but the idea that you own this stuff, the idea that it’s special, that you’re special, is just a convenience that we stumble upon some time in the first year or two of life (and that gets reinforced by some ill-conceived strains of parenting, perhaps designed to foster life-long anxiety. I mean, being the centre of the universe has got to be hard to keep up).

the stuff going on outside you is all just stuff going on. (I realize this is a truly inadequate summary of the main tenets of Buddhism. I’m no Buddhist scholar, as mentioned, so why pretend.) True, consciousness seems to illuminate the stuff going on inside you and around you in a particular way, but the idea that you own this stuff, the idea that it’s special, that you’re special, is just a convenience that we stumble upon some time in the first year or two of life (and that gets reinforced by some ill-conceived strains of parenting, perhaps designed to foster life-long anxiety. I mean, being the centre of the universe has got to be hard to keep up).