Last week I was trying to think like a Buddhist, in preparation… I thought about the self-reinforcing nature of “attachment” (à la Buddhism) and the self-reinforcing nature of addiction (which we all know about from our, ahem, independent research). What Buddhists describe as the lynchpin of human suffering, the one thing that keeps us mired in our attachments, unable to free ourselves, is exactly the same thing that keeps us addicted. The culprit is craving and its relentless progression to grasping.

The cycle of human attachment is represented in Buddhism by a wheel that keeps on turning. First comes emptiness or loss, then we see something attractive outside ourselves that promises to fill that loss, then we crave — a state we all know and love. Craving seems to be a universal form of anxiety, focused on a goal rather than a threat. So we crave and crave, and here comes the clincher: the next thing we do is grasp — reach for it. That’s what keeps the whole wheel spinning, like a merry-go-round you can’t stop. Grasping of course leads to getting. Getting leads to more attachment. Attachment leads to more emptiness and loss, because the thing we’ve attached ourselves to is never enough to fill the void. And so we’re embarked on the next revolution of the wheel — searching for something outside ourselves.

The parallels with addiction are so obvious, I won’t bother to list them. I guess the only thing that’s special about addiction is that we keep grasping for the same thing again and again. There are good neural reasons for that — reasons the Buddhists may not have appreciated. Each cycle of craving, grasping, and loss leaves its trace on the synaptic architecture of our brain. The synapses that represent the addictive substance or behaviour, the getting or doing it, and the expected relief become increasingly reinforced each time they are activated. “What fires together  wires together.”

wires together.”

As far as I know, Buddhist common sense recommends breaking the cycle between craving and grasping. Is it possible to remain in a state of craving without going after it — the thing you so badly want? Of course it’s possible, but it ain’t easy.

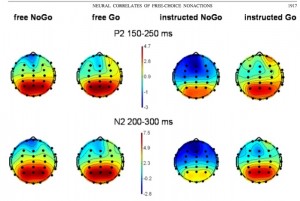

A paper published by Kuhn, Gevers, and Brass (2009, Journal of Neurophysiology) reports on a neat experiment. These guys measured electrical activity in the area of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (the dACC: the region responsible for effortful self-control), using brain wave signatures called event-related potentials. On most trials, the subjects were instructed to press one or two buttons in response to a pattern on the screen (called the “instructed Go” condition). But on some trials they were told not press the button (to withhold the action, called “instructed NoGo”). And on other trials, they were free to press or not press, according to their own whims (called “free Go” and “free NoGo”). Given this design, the researchers were able to compare the level of brain activity (in the region of the dACC) between instructed actions, free actions, instructed non-actions, and free non-actions.

The point is that instructed non-actions (“instructed NoGo’s”) are exactly what we face when we tell ourselves NOT to grasp, not to go for another drink, another bite, another pill or whatever. When you hold in mind the “instruction” not to do something, and you successfully obey your own instruction, then you’ve broken the cycle, at least for now. You’ve refrained from doing something you were just about to do: that’s craving without grasping.

The diagram showing the results of the experiment gives voltage values for different brain regions in each of the four conditions. In the second row, the “N2” tells the whole story. The N2 is considered a measure of self-control, and the N2 shows the maximum voltage (blue colour, because the voltage is negative rather than positive) in the “instructed NoGo” condition, not the “instructed Go” condition or either of the “free” conditions. So your brain, and specifically your dACC, is working hardest when it’s trying to refrain from doing something — harder than when it’s trying to do something. In Buddhist terms, it’s a lot easier to grasp than to refrain from grasping. And if you’ve been following my previous posts, you know where that self-restraint can lead: ego fatigue! Your dACC can’t take the strain and sooner or later gives up.

So here’s an instance where neuroscience and Buddhism tell us complementary aspects of the same story. Neuroscience tells us how hard it is to intentionally refrain from something you’re about to do. Buddhism tells us: Yes, it’s hard, but do it anyway! And you’ll be glad you did… That makes sense to me. If you can let yourself crave without grasping, even a few times, then you start to break down that automatic progression — that compelling momentum — that keeps the wheel going round and round. And after a while craving itself begins to diminish, because it’s got nowhere to go.

So here’s an instance where neuroscience and Buddhism tell us complementary aspects of the same story. Neuroscience tells us how hard it is to intentionally refrain from something you’re about to do. Buddhism tells us: Yes, it’s hard, but do it anyway! And you’ll be glad you did… That makes sense to me. If you can let yourself crave without grasping, even a few times, then you start to break down that automatic progression — that compelling momentum — that keeps the wheel going round and round. And after a while craving itself begins to diminish, because it’s got nowhere to go.

My family and I are going back to Toronto for two weeks to meet up with friends and family. So I may take a break from blogging — unless something really interesting comes along. Meanwhile, Happy Holidays to all of you! And thanks again for your warm good wishes last week — That’s the best present I could have wished for.

Leave a Reply