I haven’t been blogging much lately, mainly because I’ve been busy with other things. One of those things has been writing a review of Jordan Peterson’s book, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. The review was  commissioned by the Literary Review of Canada (LRC) — the Canadian cousin of the New York Review of Books. And it really got me thinking on how to solve the central problems in overcoming addiction (what many call “recovery”).

commissioned by the Literary Review of Canada (LRC) — the Canadian cousin of the New York Review of Books. And it really got me thinking on how to solve the central problems in overcoming addiction (what many call “recovery”).

(Addendum: my review just got published. You can find it here.)

Peterson is an international phenomenon by almost any standard. He has amassed millions of YouTube followers and a stream of interviews from talk show hosts. His book was the top seller (overall!) on Amazon for at least two months and is still #6, four months  after publication. A professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, Peterson has been cheered and even glorified for his radical approach to self-improvement — presented in his new book and his many online lectures. What he proposes is a set of guidelines highlighting self-honesty, personal responsibility, and what we in the addiction world have long emphasized as

after publication. A professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, Peterson has been cheered and even glorified for his radical approach to self-improvement — presented in his new book and his many online lectures. What he proposes is a set of guidelines highlighting self-honesty, personal responsibility, and what we in the addiction world have long emphasized as  the bedrock of growth, empowerment — believing in your own intentions, intuitions and capacities for change. But Peterson has also been a lighting-rod for criticism. His detractors claim that he is anti-feminist, anti-LGBT, anti-social justice, and a voice

the bedrock of growth, empowerment — believing in your own intentions, intuitions and capacities for change. But Peterson has also been a lighting-rod for criticism. His detractors claim that he is anti-feminist, anti-LGBT, anti-social justice, and a voice  for the politically incorrect (shudder) alt-right. This reaction has activated a subset of Peterson followers who are indeed highly conservative or libertarian, and sometimes quite vicious in their attacks on Peterson’s critics. But we have to extract Peterson’s message from the surrounding political hubbub. In my view he’s neither left-wing nor right-wing. As I emphasize in my review, he speaks as an individual, not a political movement.

for the politically incorrect (shudder) alt-right. This reaction has activated a subset of Peterson followers who are indeed highly conservative or libertarian, and sometimes quite vicious in their attacks on Peterson’s critics. But we have to extract Peterson’s message from the surrounding political hubbub. In my view he’s neither left-wing nor right-wing. As I emphasize in my review, he speaks as an individual, not a political movement.

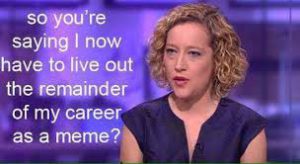

If you haven’t heard of Peterson or listened to any of his many online lectures, here are a few goodies: A discussion of the book in a lengthy interview with Dave Rubin. A shorter version, in lecture format . An oft-clicked, contentious interview with Cathy Newman, a feminist British reporter and presenter.

. An oft-clicked, contentious interview with Cathy Newman, a feminist British reporter and presenter.

So what’s all this got to do with addiction? I had to get pretty deeply into the book, and in the process listened to a lot of Peterson online, in order to write an intelligent review. In doing so, I found myself very often drawn to Peterson’s recipe for self-improvement. I think his advice is both practical and potent for people struggling with addiction, and I intend to use it more and more in my own work.

People in addiction have three main problems:

1. They want to create a massive change in their lives, but the change is so massive that it overwhelms their capacity for self-control, self-direction, choice, or whatever you want to call it. So they fail, again and again.

2. Because they fail at doing the one thing they know they should and must do (and usually want to do), they experience enormous levels of shame and guilt, often taking the form of a critical, self-denigrating  internal dialogue.

internal dialogue.

3. The third problem is that problem #2 (self-denigration) fuels the depression and pessimism that greatly contribute to problem #1. A horribly vicious circle.

In my view, Peterson has some really good suggestions for overcoming both problems 1 and 2, which of course eliminates the existence of problem 3. I’m going to give you the gist of those suggestions here and then expand on ways of implementing them in my next two posts.

1. Peterson’s approach to problem 1 comes to the surface in this talk, about 33 minutes in:

You need a goal, but we don’t want your distance from the goal to crush you…Set a high aim, but differentiate it down so you know what the next step is. And then make the next step difficult enough so

that you have to push yourself past where you are, but also provide yourself with a reasonable probability of success.

Of course the next question should be, How do you set up incremental sub-goals in the case of drug addiction? Shouldn’t you Just Say No to Drugs? I don’t think so. In my psychotherapy with people in addiction, I try to aim at steps in the right direction, beginning with controlled use or harm reduction. More on that to come.

2. Peterson’s approach to problem 2 is also highly practical but a bit more nuanced. To give you a sense of it, I’ll quote a few sentences from my review:

Peterson says “the self-denigrating voice…weaves a devastating tale.” Engage with the internal critic, he urges. Don’t listen to its exaggerated claims that you’re completely worthless. But don’t ignore it either. “Called upon properly, the internal critic will

suggest something to set in order, which you could set in order…voluntarily, without resentment.” In other words, with a little work, that voice can become a valuable ally.

Again, the question is, How? How do you turn a damning, denigrating internal critic into a negotiating partner who can help you move ahead? I’ll provide some concrete ideas two posts from now.

Jordan Peterson seems to understand how hard it is to achieve necessary changes in how we approach life, especially when it comes to breaking entrenched habits of thought and behaviour. He approaches these challenges with both the compassion of a fellow traveller and the practical  wisdom of a good clinical psychologist. He also ties his ideas to compelling lines of thought from philosophy (especially Nietzsche), social science, evolutionary theory, and even religion. A fascinating thinker, overall, with an especially helpful perspective for refashioning psychological approaches to addiction.

wisdom of a good clinical psychologist. He also ties his ideas to compelling lines of thought from philosophy (especially Nietzsche), social science, evolutionary theory, and even religion. A fascinating thinker, overall, with an especially helpful perspective for refashioning psychological approaches to addiction.

Leave a Reply