I’ve generally felt critical of the “disease” label for addiction. But having read your many comments and looked up some recent literature, I can now give it its due. In my last post, I argued that models and metaphors are not intrinsically different. A metaphor is a kind of model. And I commented that the different metaphors/models of addiction work differently for different people. So the way a model functions should be a criterion for its acceptance.

I’ve generally felt critical of the “disease” label for addiction. But having read your many comments and looked up some recent literature, I can now give it its due. In my last post, I argued that models and metaphors are not intrinsically different. A metaphor is a kind of model. And I commented that the different metaphors/models of addiction work differently for different people. So the way a model functions should be a criterion for its acceptance.

But what about the “disease” model? Psychiatrists – because they are doctors – rely on categories to understand people’s problems, even problems of the mind. Every mental and emotional problem fits a label, a medical label, from borderline personality disorder to autism to depression to addiction. These conditions are described as tightly as possible, and listed in the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and the ICD (International Classification of Diseases) for anyone to read.

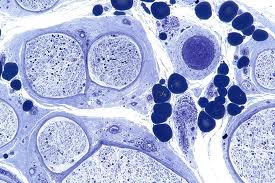

The idea that addiction is a type of disease or disorder has a lot of support. I won’t try to summarize all the terms and concepts used to define it, but Steven Hyman does a good job (thanks to Elizabeth for the link). His argument, which reflects the view of the medical community (e.g., NIMH, NIDA, the American Medical Association), is that addiction is a brain disease. (Also see this piece in the Huffington Post.) Addiction is viewed a condition that changes the way the brain works, just like diabetes changes the way the pancreas works. Specifically, the dopamine system is altered so that only the substance of choice is capable of triggering dopamine release to the nucleus accumbens (ventral striatum), while other potential rewards do so less and less. The nucleus accumbens (NAC) is responsible for goal-directed behaviour and for the motivation to pursue goals, as I’ve described in detail in my book.

Different theories propose different variants. For some, dopamine means pleasure. If only drugs or alcohol can give you pleasure, then of course you will continue to take them. For others, dopamine means attraction. Berridge’s theory (which is the one I follow) shows that cues related to the object of addiction become “sensitized,” so they greatly increase dopamine and therefore attraction…which turns to craving when the goal is not immediately available. But pretty much all the major theories agree that dopamine metabolism is seriously altered by addiction, and that’s why it counts as a disease. The brain is part of the body, after all.

What’s wrong with this definition? Not much. It’s pretty accurate. It accounts for the neurobiology of addiction much better than the “choice” model and other contenders. It explains the helplessness addicts feel: they are in the grip of a disease, and so they can’t get better by themselves. It explains the incredible persistence of addiction, its proneness to relapse, and it explains why “choice” is not the answer (or even the question). That’s because choice is governed by motivation, which is governed by dopamine, and your dopamine system is “diseased.”

So, do I buy it? Not really. I do think it’s often very helpful. It truly does help alleviate guilt, shame, and blame, and it gets people on track to seek treatment. Moreover, addiction is indeed like a disease, and if I follow my own words, then a good metaphor and a good model aren’t much different. Their value depends on their usableness.

Then why don’t I buy it? Mainly because every experience that has some emotional content changes the NAC and its uptake of dopamine. Yet we wouldn’t want to call the excitement you get when you’re on your way to visit Paris, or your favourite aunt, a disease. Each rewarding experience builds its own network of synapses in and around the NAC, and that network sends a signal to the midbrain: I’m anticipating x, so send up some dopamine, right now! That’s true of Paris, Aunt Mary, and heroin. In fact, during and after each of those experiences, that network of synapses gets strengthened: so the “specialization” of dopamine uptake is further increased. London just doesn’t do it for you anymore. It’s got to be Paris. Pot, sex, music…they don’t turn you on that much; but coke sure does. Physical changes in the brain are its only way to learn, to remember, and to develop. But we wouldn’t want to call learning a disease.

So how well does the disease model fit the phenomenon of addiction? How do we know which urges, attractions, and desires are to be labeled “disease”, and which are to be considered aspects of normal brain functioning? There would have to be a line in the sand somewhere. Not just the amount of dopamine released, not just the degree of specificity in what you find rewarding: these are continuous dimensions. They don’t lend themselves to two (qualitatively) different states: disease and non-disease.

Thus, addiction doesn’t fit a specific physiological category. But what about the functionality, the useability, of the disease model? That’s disputable. It works well for some, not at all for others. And I think that’s because addiction is an extreme form of normality, if I can say such a thing. The function of modelling addiction as a disease is limited because “disease” and “normality” are overlapping, not mutually exclusive, when it comes to the mind and the brain. Yet we sure recognize addiction as distinct from “normal” in our everyday lives. That’s the problem.

My solution will come several posts from now. Meanwhile, I hope readers will comment on other aspects of the disease model that fit, or that don’t fit, the phenomenon of addiction.

Leave a Reply to Michele Patterson Cancel reply