If you weren’t completely sold on the bicycle analogy. Try this one. The point is the same, and it’s not complicated: addiction is a mental habit, it grows, stabilizes, and gets difficult to reverse. But it’s not permanent. It can be reversed — with practice. Unfortunately, the good habits that replace it may not be permanent either.

Mental habits become stable and resilient, hard to switch out of, when they are practiced repeatedly. That’s the case with piano lessons, pizza night, bicycling, and heroin. (I don’t distinguish “cognitive” habits from motor habits like bicycling — they’re all grounded in the same brain.) It’s possible to switch out of one mental habit and settle into another incompatible habit; that’s all well and good. Except that you might switch back into the old habit if you’re not careful. Because the synaptic configuration that held that pattern in place isn’t gone. It’s just been “deactivated.” Synaptic patterns take a long time to fade — through a process known as synaptic pruning. And the only way that’s going to happen is if other habits are practiced in their place.

Until that occurs, you’ve got these two habitual mental frames, let’s call them drug-wanting and drug-shunning. I recently referred to them as “two you’s.” They’re incompatible. One disappears when the other takes over. And it’s not hard to switch from one to the other — either by accident or on purpose.

So here’s another example: the Necker cube. (I don’t know who Necker was….maybe the guy who discovered this cool optical illusion.)

Take a look at it:

Pretty, isn’t it? Now try seeing the face that includes the lower left corner as the outer face — the face facing you. Easy enough, right? Just stare for awhile. Get used to it. Then imagine a different orientation: imagine that that face is actually at the back, and the front face is the one pointing up and rightward (and including the top rightmost corner) rather than down and leftward. Can you do it? It might take a while, but if you blink a few times and/or move your head around, you should get it. But it’s delicate — like early recovery. Blink again…and your former interpretation might spring back to mind, making the second interpretation highly effortful once more.

Of course these two “interpretations” of the structure of the cube are incompatible. They can’t coexist. Just like the you who eagerly anticipates getting high can’t exist at the same time as the you who is in control, centered, and connected to the future. These two you’s are incompatible! But they can switch. So watch out!

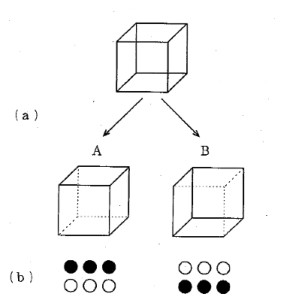

Now take a look at this diagram:

This represents, in a very simple way, that each version of the Necker cube can be represented by the same group of neurons. Here there are only six neurons involved — obviously an unrealistic number. But line (b) is showing us that a different pattern of activation on the same set of neurons projects a different interpretation of the cube.

Now imagine that you have one (much larger!) group of neurons representing the two interpretations you have of your drug of choice: let’s say cocaine-good and cocaine-bad are the two versions. A different pattern of activation on that same macroset of neurons will produce one or the other version. And the two versions can easily switch, as the activation of the neurons shifts, due to….well, due to the way you’re feeling, the way you’re thinking, how much you slept last night, whether or not your dealer just called, whether you had a coke dream recently, whether you just got a raise at work…or lost your job. I’m sure you know what I’m saying.

In some ways addiction is very complicated. But in other ways, it’s pretty simple. Mental habits can be considered, reflected on, worked with, played with….and they can ultimately be controlled — with practice — though perhaps not entirely.

Leave a Reply to Robin Roger Cancel reply