So here’s the resolution that occurred to me.

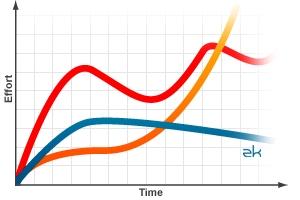

The problem was that the learning curve that describes addiction onset is often unusually steep — what I’ve called accelerated learning. But the biographies I include in the book, and other tales of addiction sent my way, sometimes show a gradual onset — a period of coasting before substance use takes off. And sometimes there are plateaus, or even remissions, when our addictions may live underground. We might hear them stirring late at night, but they don’t always rise up and send us on another cliff-hanging romp with self-imposed torture.

So I wanted to come up with a description of addictive learning that allows for accelerated learning but also gradual onsets and plateaus. The following is a (slightly edited) passage from the final draft of the second-last chapter, sent to my publisher this morning. It’s not particularly new or amazing, but I think it covers the issue. And serious thanks to you guys for the suggestions and insights you posted or emailed to me. They helped me think it through.

Brain changes naturally settle into brain habits — which lock in mental habits. And the experiences that get repeated most often, most reliably, and that actually change synapses rather than just passing through town, are those that are emotionally compelling. Most important, combining strong motivation — such as desire — with frequent repetition changes the rate of learning. It speeds up the feedback cycle between experience and brain change. This kind of accelerated learning is bound to boost the entrenchment of long-term habits, for several reasons:

- because desire focuses attention like nothing else, and attention is the springboard to learning.

- because addiction offers highly desired rewards that disappear before long, thus priming the desire pump repeatedly.

- because a feedback loop that cycles faster will generate more of whatever it generates, thus accelerating its rate further. This is the well-known snowball effect.

- because any growth process that is speeded up enough will outrun its competitors. Since synapses fade and disappear when they are no longer in use, and since addictions are pursued at the expense of other goals, addictive habits come to usurp habits incongruent with addiction — like caution, integrity, and empathy.

The onset of addiction doesn’t always looks like an accelerated learning curve. The biographies of Brian and Donna show us that people can take drugs for a long time before they become addicted. Brian’s use of stimulants and Donna’s use of opiates had little motivational thrust for that initial period. Brian was trying to remain awake and alert so he could accomplish work goals, and Donna was taking Vicodin for pain long before she took it for pleasure. Nevertheless, both Brian and Donna reached a turning point, at which the learning curve must have risen steeply. For Donna, this occurred more than once, since there were periods of calm between her drug-stealing storms. The learning spiral would have first quickened, showing a snowball effect in behavior and a cascade of neural changes, when Donna and Brian began to pursue drugs for the feelings they provided, not as a means to an end — when desire kicked in and their quest for drugs overrode their other goals, including the wish to avoid big risks. That’s when their lives started to unravel.

Because the onset of addiction must include one or more phases of accelerated learning, but can also simmer for long periods, I’ve settled on the phrase “deep learning.” This is meant to cover the overall profile of addictive learning, including periods of rapid change and periods of coasting (or even periods of abstinence — “remission” in medical parlance). Note that this profile corresponds with models that view the onset of addiction as a series of stages or steps.

That said, I want to wish you all a calm, happy, warm, peaceful holiday. May we all be free of our demons and let the holiday maelstrom of emotions pass without harm.

Leave a Reply to Matt Cancel reply