Last post I described common denominators between drug addiction and compulsive gambling. Today I want to ask: how do we assign responsibility for promoting products that benefit some while seriously harming others — because they are too attractive?

I got back from my trip to Australia about three days ago and I can finally see straight this morning. I came home travel weary but armed with some great new insights and perspectives. Most of what I learned was by way of the “Many Ways to Help” conference organized by the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. In particular, the counsellors, case workers, policy makers, and researchers in the audience and at the podium repeatedly raised the question of responsibility — and how responsibility is related to technology, access, and profit.

Let me unpack that. Gamblers in the Melbourne area come in droves to the Crown Casino, a multi-level pleasure palace packed with every conceivable form of entertainment and an enormous number of high-tech slot machines distributed among the bars, bandstands, restaurants, craps and roulette tables…along every  corridor, in every nook and cranny. These machines have been designed to appeal to a great variety of individual tastes. In some, the spinning character set settles into a poker hand — usually a losing hand. Others rely on matches among fruits, goblins, jewels, and shining, flickering, mesmerizing tokens lifted from fairy tales and Kung Fu movies. Some mix cards, dice, and fairy-tale images on their glittering screens. The variety and artistry are incredible.

corridor, in every nook and cranny. These machines have been designed to appeal to a great variety of individual tastes. In some, the spinning character set settles into a poker hand — usually a losing hand. Others rely on matches among fruits, goblins, jewels, and shining, flickering, mesmerizing tokens lifted from fairy tales and Kung Fu movies. Some mix cards, dice, and fairy-tale images on their glittering screens. The variety and artistry are incredible.

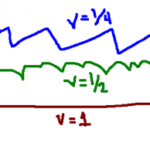

What offers all this excitement, this sense of fun, and what keeps gamblers playing and losing and playing and losing, derives from innovations in design,

What offers all this excitement, this sense of fun, and what keeps gamblers playing and losing and playing and losing, derives from innovations in design,  programming, psychological modeling, video game development, and the technological know-how to package all these in a single product. And of course the paycheques of the designers, programmers, artists, and so forth come from a casino industry that rakes in enormous profits.

programming, psychological modeling, video game development, and the technological know-how to package all these in a single product. And of course the paycheques of the designers, programmers, artists, and so forth come from a casino industry that rakes in enormous profits.

The attendees at the conference were pretty pissed off. Because, despite the various placards encouraging gamblers to take it easy, and despite various government regulations that force casinos to notify gamblers when they’ve reached the danger  zone, there’s a confluence of factors that attract people to play as much as possible. Especially at the slot machines, where play becomes almost mindless (see

zone, there’s a confluence of factors that attract people to play as much as possible. Especially at the slot machines, where play becomes almost mindless (see  previous post). The conference attendees spend their lives trying to help people who continue to lose — not only their money but their homes, marriages, interpersonal relationships of all sorts, and even their lives — sometimes directly via suicide, sometimes slowly through the alcoholism and other forms of escape that ride on gambling addiction. It just doesn’t seem fair. The casinos know what they’re doing, and they’ve got the resources to do it very effectively.

previous post). The conference attendees spend their lives trying to help people who continue to lose — not only their money but their homes, marriages, interpersonal relationships of all sorts, and even their lives — sometimes directly via suicide, sometimes slowly through the alcoholism and other forms of escape that ride on gambling addiction. It just doesn’t seem fair. The casinos know what they’re doing, and they’ve got the resources to do it very effectively.

But there’s another side to this argument. The casinos (and other gambling outlets — I’ve chosen slot machines at casinos as an overt example) are just businesses. They exist to make money, pay their employees, and increase their profits, just like any other business. Does it make sense to blame them for being good at what they do? Is it their responsibility to protect the fewer than 1% of adults in the Melbourne area who are “problem gamblers” (and the 2.4% who are “moderate-risk gamblers”)? See recent research findings here. Or should the government come down hard on an industry that brings pleasant entertainment to many but serious harm to a few? These are some of the questions at the forefront of the discussion about problem gambling in Australia. And the same questions are debated just as hotly in the US and the UK.

If the answer is “maybe,” then let’s take the argument further: Should the manufacturers of fast cars be held responsible for accidents that result from speeding? Should the makers of video

If the answer is “maybe,” then let’s take the argument further: Should the manufacturers of fast cars be held responsible for accidents that result from speeding? Should the makers of video  games like The Sims and Candy Crush be penalized for making the most attractive (and addictive) games ever known? Should Facebook be banned? Nir Eyal has a fascinating blog that explores the issues and ethics at the core of addictive technology, and the answers to these questions aren’t simple.

games like The Sims and Candy Crush be penalized for making the most attractive (and addictive) games ever known? Should Facebook be banned? Nir Eyal has a fascinating blog that explores the issues and ethics at the core of addictive technology, and the answers to these questions aren’t simple.

Aren’t adult humans supposed to be responsible for controlling their own impulses? After all, the world is full of temptations, some of them natural, some manufactured. It’s hardly conceivable to block temptations at the source, especially when most people can steer around them quite successfully. And would we want a world that minimizes tempting attractions, even if we could achieve it?

Where this conundrum interests me most is where it intersects with the problem of drug addiction. And alcoholism. The parallels are mind-blowing. First, stigmatization, family disintegration, avenues of treatment, and support groups continue to blossom in both realms. Second is the question of making profits off people’s suffering. Third, how do we balance the suffering of the few against possible benefits to the many? The sale of addictive drugs like heroin, methamphetamine, and crack line the pockets

Where this conundrum interests me most is where it intersects with the problem of drug addiction. And alcoholism. The parallels are mind-blowing. First, stigmatization, family disintegration, avenues of treatment, and support groups continue to blossom in both realms. Second is the question of making profits off people’s suffering. Third, how do we balance the suffering of the few against possible benefits to the many? The sale of addictive drugs like heroin, methamphetamine, and crack line the pockets  of drug lords and gangsters, but they also pay simple farmers all over South America and Asia. And the legal addictive drugs like oxycodone and Vicodan (most famously) certainly profit Big Pharma, but they

of drug lords and gangsters, but they also pay simple farmers all over South America and Asia. And the legal addictive drugs like oxycodone and Vicodan (most famously) certainly profit Big Pharma, but they  also provide badly needed relief for the millions suffering pain. Next, should we restrain what might be called the technology of attraction at all? The substances I just listed, as well as modern slot machines and internet gambling, evolved from links between profit and technology. Technology needs money (e.g., profit) to grease its wheels. Even scotch whiskey — at least the good scotch that I like — is the product of an industry that harms a portion of its users while feeding some of its profits into technological advancement. Alcoholism kills 88,000 Americans per year. Yet almost nobody recommends a return to Prohibition.

also provide badly needed relief for the millions suffering pain. Next, should we restrain what might be called the technology of attraction at all? The substances I just listed, as well as modern slot machines and internet gambling, evolved from links between profit and technology. Technology needs money (e.g., profit) to grease its wheels. Even scotch whiskey — at least the good scotch that I like — is the product of an industry that harms a portion of its users while feeding some of its profits into technological advancement. Alcoholism kills 88,000 Americans per year. Yet almost nobody recommends a return to Prohibition.

So maybe it’s the same problem in general — the same problem for gambling industries, video game makers, social media designers, drug manufacturers, and distilleries with exotic names like Glenkinchie and Laphroaig. Many of the products that make modern life fun, pleasant, interesting — or even just bearable — for many of us also make life hell for those who lose control. Should we assign blame for making, selling, or buying something that’s too desirable? Do we just turn responsibility over to the user, or is there a sensible way to restrain the dealer? Is there any concept of regulation, packaged warnings, education, or harm reduction that could help across the board?

So maybe it’s the same problem in general — the same problem for gambling industries, video game makers, social media designers, drug manufacturers, and distilleries with exotic names like Glenkinchie and Laphroaig. Many of the products that make modern life fun, pleasant, interesting — or even just bearable — for many of us also make life hell for those who lose control. Should we assign blame for making, selling, or buying something that’s too desirable? Do we just turn responsibility over to the user, or is there a sensible way to restrain the dealer? Is there any concept of regulation, packaged warnings, education, or harm reduction that could help across the board?

I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Leave a Reply to Carmelia Cancel reply