In response to my last post, some of you expressed interest in mindfulness/meditation as a means for overcoming addiction. Today I want to relate the calm centre of IFS with the calm place we find in meditation. They are similar in some ways and very different in others.

There will be more posts on mindfulness, and I promised to visit “Mindfulness-based Relapse Prevention”, a fusion of mindfulness with CBT expressly developed for addiction. But today’s post will be about my personal experiences and thoughts.

Last night I sent the finally-fully-edited draft of my first novel to my agent. I’ve been working on this manuscript for roughly four years, so you can imagine, today I feel this sort of yawning emptiness. Like, now what am I supposed to do? The day seems to lack structure and meaning. I have moments of delicious relief, but at other times I feel confused and lost.

So I did my morning meditation (nothing heroic — just 12 minutes with the Sam Harris Awakening app) and it happened to be an episode focused on emotions. True to Buddhist tradition, Sam H urged us to let emotions come…and go. Anger, anxiety, whatever it is, let yourself feel it, don’t fight it, don’t hold onto it, just recognize it as colouring the field of consciousness. And that’s all, he reminds us. You don’t have to do anything, because consciousness is its own goal. Just be there and be aware.

I figure this is the centrepiece of (Vipassana?) mindfulness meditation. Good stuff, to be sure. Especially when craving is a real problem. Recognizing that craving is simply a feeling, without a particular requirement or needed resolution, can be most beneficial.

But nowadays when I meditate I often go into IFS land. (See my last eight posts if you’re not familiar with IFS, or go online). It’s different. The emotions I felt this morning, while meditating, were mostly a mix of anxiety and resentment, tinged with a wish to rebel or even get high. So…what the fuck’s that about? Simple, according to mindfulness meditation: let the feelings be there without being carried away. Simply let yourself be aware of them. What does IFS say?

In IFS, as I’ve tried to explain, there’s a place they call Self (with a capital-S) which is different from the “parts”. It is a place of being centred, calm, patient, compassionate, accepting, noticing, even welcoming whatever comes. As you can imagine, whatever comes usually involves the “parts” that have needs, concerns, and fears. Now this central place of calm acceptance seems very similar to the calm place you get to in meditation. But here’s the difference. You don’t just sit there in the centre of it, you meet and greet, as it were, the parts that need something. You connect with them, welcome them, follow them to their origins…you can sit with them, and you can soothe them. One form of soothing is to invite the parts to come and be with You (captital Y?) in the present, away from the bleak place where they remain fixated. A mysterious and perhaps mystical process that can work wonders.

So today I went and followed the dissatisfied angry part to get to know it better.

I had an experience of sexual assault in my teenage years. I have never disclosed this publicly, but after listening to Tim Ferriss (a very popular podcaster) disclose his history of sexual abuse, I thought, what am I trying to hide? Many of us who’ve been addicted have experienced something similar. In fact the link between trauma and addiction is well known. I want to understand this link in my own life. To look the other way is unhelpful — both personally and as part of a community.

I’ll leave it at that, without details, for now. The aftermath is what preoccupies me.

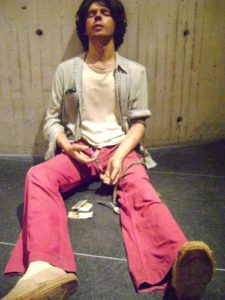

My first year in Berkeley, California. It’s 1968-69. The sun is shining, exotic flowers and trees line the streets, the hippie types (including me, sort of) wear their colourful clothes with playful exuberance. There were smiles on many faces. Fascinating men, beautiful women. We felt like we were ushering in a new age of humanity, a real cultural revolution.

My first year in Berkeley, California. It’s 1968-69. The sun is shining, exotic flowers and trees line the streets, the hippie types (including me, sort of) wear their colourful clothes with playful exuberance. There were smiles on many faces. Fascinating men, beautiful women. We felt like we were ushering in a new age of humanity, a real cultural revolution.

But I was lost. I wandered the streets feeling empty and unreal. I didn’t know what to do with myself. Depression crashed down on me every evening I was alone — that is, without my roommate or my part-time girlfriend, Susan. I had a very hard time being with family members, because I felt there was something deeply wrong with me, beneath contempt. I resented the walls of politeness that seemed to shut me out of their lives. I lived in a pool of shame that was almost impossible to sense clearly because it was so constant. I have no doubt that my traumatic experience created or refined this part of me — broken, shamed, empty.

But I was lost. I wandered the streets feeling empty and unreal. I didn’t know what to do with myself. Depression crashed down on me every evening I was alone — that is, without my roommate or my part-time girlfriend, Susan. I had a very hard time being with family members, because I felt there was something deeply wrong with me, beneath contempt. I resented the walls of politeness that seemed to shut me out of their lives. I lived in a pool of shame that was almost impossible to sense clearly because it was so constant. I have no doubt that my traumatic experience created or refined this part of me — broken, shamed, empty.

But there was one way to feel better, to feel…vital. Drugs. You can bet there were a lot of drugs available in Berkeley in those days. And they worked. From cannabis I went to psychedelics, acid two or three times a week, riding my motorcycle through thickets

But there was one way to feel better, to feel…vital. Drugs. You can bet there were a lot of drugs available in Berkeley in those days. And they worked. From cannabis I went to psychedelics, acid two or three times a week, riding my motorcycle through thickets  of hallucinations, and then from psychedelics to heroin, and then on to pharmaceuticals and crime. Check out my first book on addiction — Memoirs of an Addicted Brain — for the gory details. Two parts of me: one sinking into this sickening, passive emptiness, this incoherent shame, the other energized to find new and more powerful drugs and drug-tinged adventures, to fill up that empty space with magical potency. And through drug use, defy everyone who’d tried to tell me how to behave.

of hallucinations, and then from psychedelics to heroin, and then on to pharmaceuticals and crime. Check out my first book on addiction — Memoirs of an Addicted Brain — for the gory details. Two parts of me: one sinking into this sickening, passive emptiness, this incoherent shame, the other energized to find new and more powerful drugs and drug-tinged adventures, to fill up that empty space with magical potency. And through drug use, defy everyone who’d tried to tell me how to behave.

The wounded part never went away. Nor did the defiant part. That’s a fundamental insight of IFS: the parts can evolve, but they don’t disappear. As for the wounded part, its sense of being lost and helpless still hobbles me with a certain anxiety, vulnerability, and hesitation — but not nearly as much as it did. And I have other strong, brave parts with impressive energy. Often they lead — sometimes brilliantly.  Now, when my meditation leads me to my wounded parts, I greet that 17-year old kid and let him know that it’s not his fault, that I accept him completely — him and his 12-year spree of crime and self-abuse — and that I love him. I let him know that he doesn’t have to live in that crazy, tilted world anymore. And that’s all he needs, that acceptance and care. It heals him.

Now, when my meditation leads me to my wounded parts, I greet that 17-year old kid and let him know that it’s not his fault, that I accept him completely — him and his 12-year spree of crime and self-abuse — and that I love him. I let him know that he doesn’t have to live in that crazy, tilted world anymore. And that’s all he needs, that acceptance and care. It heals him.

……………..

I should mention that Ferriss also interviews Richard Schwartz, the founder of IFS in a recent episode. This is a cool podcast: Schwartz explains IFS succinctly, compares it to aspects of psychedelic (MDMA) psychotherapy (fascinating!), and then does a live IFS session with Ferriss as the client.

Leave a Reply to Alison Cancel reply