Hi again. Sorry I’ve been so…absent…lately, but I’ve had a number of ideas I’d like to share with you in the next few weeks. The first involves psychedelics, whose benefits have long remained mysterious. We are finally getting a glimpse of how psychedelics work to improve mental health. And it’s fascinating. So consider this a sequel to the post before last.

I hope you read Eric Nada’s guest post on the promise of psychedelic therapy for helping overcome addiction. Eric reviewed the therapeutic side of psychedelic therapy, and he stressed the importance of working with a knowledgeable and supportive therapist. He emphasized the transformative power of psychedelics, and pointed out that recovery from addiction requires transformation in how we think and feel.

Here I want to focus on how psychedelics act on the nervous system, whether they are taken in a controlled setting with a therapist or on a hilltop in the forest. How do these drugs actually work? Eric began his post remarking on how counter-intuitive it feels to recommend a drug experience for people trying to overcome addiction. But I’ve never felt quite that way. Psychedelics don’t invite us to be cheered up, entertained or numbed. As Eric also concluded, they invite us to open up and change.

When I was a young man, dropping acid and climbing trails through the Berkeley Hills, what I experienced was a massive perspective change, an opportunity to be more attuned to the beauty of the natural world and to my own consciousness. During those years I was also fighting my attraction to opiates and other potentially dangerous drugs, and it took me years to resolve those issues. But LSD and psilocybin (magic mushrooms) were different animals. These substances seemed to offer a way to outgrow the rigid perseverance of my mental habits, my stuckness, my depression and my addiction. If only I could rise to the occasion.

When I was a young man, dropping acid and climbing trails through the Berkeley Hills, what I experienced was a massive perspective change, an opportunity to be more attuned to the beauty of the natural world and to my own consciousness. During those years I was also fighting my attraction to opiates and other potentially dangerous drugs, and it took me years to resolve those issues. But LSD and psilocybin (magic mushrooms) were different animals. These substances seemed to offer a way to outgrow the rigid perseverance of my mental habits, my stuckness, my depression and my addiction. If only I could rise to the occasion.

These days we are inundated with research showing that, indeed, psychedelics can help improve mental health. Anxiety and depression have been shown to be reduced by LSD and psilocybin, in various forms and doses, over dozens of studies. In a study of cancer patients, a single dose of psilocybin “produced immediate, substantial, and sustained improvements in anxiety and depression and led to…improved spiritual wellbeing…” Psilocybin has also been shown to help people quit smoking, and to relieve other addictive spirals. Psychedelics prove to be as effective or more effective than conventional antidepressant drugs for relieving depression, even if taken just once or twice. And there are no side-effects, no measurable addiction potential, and very little risk of ongoing thought disturbance. See this recent review and commentary in Scientific American.

The benefits are no longer speculative. They’re real, and mainstream psychiatry is finally starting to embrace them. But what might be the cause of such improvements? Does anybody know?

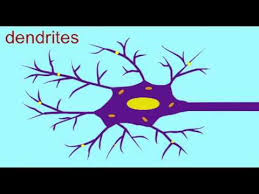

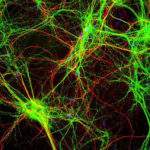

Recent research suggests that “opening up” with psychedelics has a very distinct biological basis. Published last month in Neuron, this study shows something almost unbelievable to students of the brain. We’ve been convinced (brain-washed?) for at least 50 years that brain cells don’t regenerate. (By brain  cells I mean the “grey matter,” composed of neurons and their thread-like extensions — dendrites and axons.) They are considered the only cell type in the body that does not reproduce, except for a structure called the hippocampus, and even that shows only limited change beyond early adulthood. The ominous conclusion is, of course, that the brain runs down. Aging seems to reveal a brain that loses its plasticity, its capacity for novelty and change, and even its basic functionality. More to the point, mental problems such as addiction and depression are really hard to fix. Both can be seen as products of neural entrenchment. Maybe you can grow new connections, probably that helps, but you’re stuck with the same complement of grey matter you had at the age of 18. How depressing!

cells I mean the “grey matter,” composed of neurons and their thread-like extensions — dendrites and axons.) They are considered the only cell type in the body that does not reproduce, except for a structure called the hippocampus, and even that shows only limited change beyond early adulthood. The ominous conclusion is, of course, that the brain runs down. Aging seems to reveal a brain that loses its plasticity, its capacity for novelty and change, and even its basic functionality. More to the point, mental problems such as addiction and depression are really hard to fix. Both can be seen as products of neural entrenchment. Maybe you can grow new connections, probably that helps, but you’re stuck with the same complement of grey matter you had at the age of 18. How depressing!

But maybe it’s not that way at all. The Neuron article shows that a single dose of psilocybin produced a rapid and long-lasting increase in the size and density of dendritic spines (the “twigs” that grow out of dendrites) throughout the frontal cortex. The subjects of the study were mice, not humans, but that hardly matters. When it comes to the characteristics of brain cells, like cell growth and regeneration, we mammals are all in the same boat. The researchers reported that the change took place rapidly, with 24 hours, and it was still evident one month later. The extent of growth was approximately 10  percent, a huge number when applied to spontaneous brain change. And — get this — neural transmission (excitatory connection strength) increased measurably, while stress-related behaviour diminished.

percent, a huge number when applied to spontaneous brain change. And — get this — neural transmission (excitatory connection strength) increased measurably, while stress-related behaviour diminished.

So psychedelics appear to actually grow additional grey matter! Note that this is not the same as strengthening or reinforcing synapses, something which occurs during learning but is far less extensive in terms of actual physical change and far more gradual in time. What are the implications? If psychedelics have this kind of firepower, in changing the biological substrate of cognition, then they should be able to induce rapid changes in thinking. In other words, they would be natural habit-breakers! And that’s just what it feels like — that wave of novelty, new paths opening up — to be on psychedelics, whether in a psychiatrist’s office or in the fire-lit circle of an ayahuasca ceremony.

So psychedelics appear to actually grow additional grey matter! Note that this is not the same as strengthening or reinforcing synapses, something which occurs during learning but is far less extensive in terms of actual physical change and far more gradual in time. What are the implications? If psychedelics have this kind of firepower, in changing the biological substrate of cognition, then they should be able to induce rapid changes in thinking. In other words, they would be natural habit-breakers! And that’s just what it feels like — that wave of novelty, new paths opening up — to be on psychedelics, whether in a psychiatrist’s office or in the fire-lit circle of an ayahuasca ceremony.

But when it comes to addiction and other mental-health problems, that’s only half the story. As Eric emphasized in his post, the transformative potential of psychedelics has the greatest traction when it’s guided or

directed by someone knowledgeable, whether therapist or shaman, and when we have a chance to process, practice, and consolidate what it is we are learning. As he says, “the healing benefits of psychedelics are not just produced by the compound itself but through the whole of the experience they inspire.”

directed by someone knowledgeable, whether therapist or shaman, and when we have a chance to process, practice, and consolidate what it is we are learning. As he says, “the healing benefits of psychedelics are not just produced by the compound itself but through the whole of the experience they inspire.”

Conclusions? I should clarify that single studies showing remarkable results need replication. That’s next. As well, I’d like to see the present findings jibe with other neurobiological models. In particular, research from a few years back showed that psychedelics increase connectivity across multiple neural regions, in contrast to the usual concentration and boundedness of activation within the default mode network, a region that mediates thoughts about the self (reminiscence, daydreaming, rumination). It would make sense: rapid change in neural maps would be impossible without some kind of “growth booster,” and the rapid, spontaneous improvements reported in the clinical literature point to rapid change.

So, if we take the present results seriously, the conclusion seems pretty straightforward: We use psychotherapy to help people think and understand themselves differently, so that they don’t just respond impulsively or compulsively (as in drug taking) to their needs and fears. It’s been known by various indigenous peoples, for thousands of years, that there are natural chemicals that shake people out of habitual patterns and promote mental change. And now we are starting to learn how this works at the cellular level. Bringing these streams of knowledge together seems an obvious and optimistic route toward improving our mental health…across the board.

P.S. Didn’t your mother tell you that mushrooms are good for you?

Leave a Reply to Marc Cancel reply