As promised, here’s Part 2. But note that this section (on implications for treatment) is based on eight and a half chapters you haven’t read yet. To distill some of the main points is tricky, but here goes:

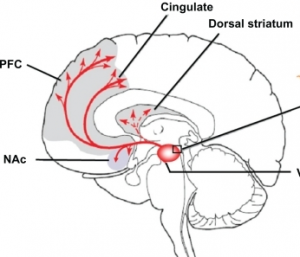

Addiction is maintained by an entrenched set of connections between the striatum — the part of the brain that generates goal-directed desire and thrust — and regions of the prefrontal cortex (e.g., the orbitofrontal cortex) that hold the goal in mind, embellish it, imbue it with value, and “remember” it as the salvation you hoped it to be. My argument about recovery is that you can’t turn off the striatum — the motivational engine. You can’t turn it off because it’s at the very center of who you are, it is the pulse and drive that moves you from one moment to the next. So, if you can’t turn off the “biology of desire”…then you have to connect it with different goals, goals that can also be consolidated by synaptic networks

Addiction is maintained by an entrenched set of connections between the striatum — the part of the brain that generates goal-directed desire and thrust — and regions of the prefrontal cortex (e.g., the orbitofrontal cortex) that hold the goal in mind, embellish it, imbue it with value, and “remember” it as the salvation you hoped it to be. My argument about recovery is that you can’t turn off the striatum — the motivational engine. You can’t turn it off because it’s at the very center of who you are, it is the pulse and drive that moves you from one moment to the next. So, if you can’t turn off the “biology of desire”…then you have to connect it with different goals, goals that can also be consolidated by synaptic networks  in the prefrontal cortex. But to do that, you need to engage yet another part of the prefrontal cortex that is critical for perspective change — the part of the brain that can make choices (the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) — what I call “the bridge of the ship.”

in the prefrontal cortex. But to do that, you need to engage yet another part of the prefrontal cortex that is critical for perspective change — the part of the brain that can make choices (the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) — what I call “the bridge of the ship.”

Sounds simple—re-engage the bridge of the ship, and get it to take on a new set of goals, goals that will synch up with the motivational engine.

Only two problems:

Problem #1. These goals for future wellbeing can only be achieved through long-term plans, not the short-term plans for immediate relief that have been central in addiction. And these long-term plans are supported by a different set of synapses than those that supported your addictive goals. Different but overlapping! As with the webbed fingers example, goals for future wellbeing and immediate relief have become fused together in addiction — but now these two synaptic patterns need to be allowed to separate. This requires thinking and feeling differently — a shift in perspective — at least for awhile. What fires together wires together, and what fires apart wires apart. The long-term plans and goals have to establish their own distinct connection with the motivational engine, with desire.

Problem #2. The goals for achieving short-term relief are highly compelling, very much in your face, hard to disengage from, because the dopamine pump continues to activate them — rapidly! I call that “now appeal” (technically, delay discounting)– and it’s a well-known obstacle to quitting. And by the way, it completely bypasses “the bridge of the ship,” the part of the prefrontal cortex necessary for perspective change.

So how do you shift the beam of desire from highly practiced short-term goals to much less practiced long-term goals — what might be called the assembly of a future self — and then reinforce the new roadwork? First, you need to avoid killing the motivational thrust that comes from you and only you. Yet becoming a “patient” (in a  disease-model-based treatment environment) is very likely to squelch that motivational thrust…. I mean, doing what you’re told is not the same thing as doing what you really want. Second, you need to act fast, strike while the iron is hot. Because the brain gets so quickly caught in the dopamine-powered pursuit of short-term relief — in now appeal — you have “catch” it when it’s looking toward something different. In other words, you have to catch it just when the “bridge of the ship” gets activated — so that desire and future wellbeing make contact. That’s when a different synaptic channel between the striatum and the prefrontal cortex can open up.

disease-model-based treatment environment) is very likely to squelch that motivational thrust…. I mean, doing what you’re told is not the same thing as doing what you really want. Second, you need to act fast, strike while the iron is hot. Because the brain gets so quickly caught in the dopamine-powered pursuit of short-term relief — in now appeal — you have “catch” it when it’s looking toward something different. In other words, you have to catch it just when the “bridge of the ship” gets activated — so that desire and future wellbeing make contact. That’s when a different synaptic channel between the striatum and the prefrontal cortex can open up.  Like an arc of static electricity leaping to a new target. And that channel is there, and it does light up. At least sometimes. Like when you wake up feeling zonked, shitty, shaky, with withdrawal symptoms revving up, looking at the deterioration of your face in the mirror, and running to the toilet — and for the next half hour you want like anything to quit. You want to choose a future. Right then, you want to quit.

Like an arc of static electricity leaping to a new target. And that channel is there, and it does light up. At least sometimes. Like when you wake up feeling zonked, shitty, shaky, with withdrawal symptoms revving up, looking at the deterioration of your face in the mirror, and running to the toilet — and for the next half hour you want like anything to quit. You want to choose a future. Right then, you want to quit.

So there’s a condensed lead-up. Now I wish I could provide a brilliant new design for optimizing treatment for addiction — one that sits like a crown on this neuro/experiential modeling. But I can’t. I don’t know enough, and I think that job really belongs to people within the treatment world, not “science writers” like me. But here are a couple of paragraphs, from the last section of my book, showing where this kind of logic might lead us. And again, my thanks to Matt Robert and Cathy O’Connor, who helped me see things from this perspective.

What alternatives might stem from a developmental approach to treatment, applying the power of momentary desire to a personal time-line for quitting? Most important, there is no single strategy, organization, method, or philosophy that commands center stage. Any approach that meets addicts when and where they’re ready to quit is well positioned to help them move onward. Community-based settings can fill this role most easily, because there is no fortress wall that needs to be scaled, no line-up at the door, and no financial minefield that needs to  be crossed. Nor, hopefully, are there rigid policies that preempt the addict’s personal incentive. When desire is ready to arc from the goal of immediate relief to the goal of a valued future, treatment can begin. Not by inducing desire—only frustration and suffering can do that—but by capturing and holding one’s vision of that future.

be crossed. Nor, hopefully, are there rigid policies that preempt the addict’s personal incentive. When desire is ready to arc from the goal of immediate relief to the goal of a valued future, treatment can begin. Not by inducing desire—only frustration and suffering can do that—but by capturing and holding one’s vision of that future.

Community-based groups, including SMART Recovery and progressive AA groups, can provide a kind of narrative scaffolding, a concatenation of stories about addiction and recovery, that can help addicts work on their own future “stories” — their personal narratives — addicts who are ready to move on. Group meetings are frequently inserted into institutional treatment as well, but whether they’re available when addicts really need them and can use them is entirely hit-and-miss. And while group processes can be helpful, they are certainly not always helpful, nor are they the only way forward. Treatment only requires the attention of one other human being who can hold, possibly distill, and hopefully extend the vision of a future self energized by an individual’s desire to change.

What will work best is whatever is available when the synaptic avenues of desire make contact with brain regions responsible for perspective change. This can be the presence of a friend who accompanies you to your first 12-step meeting, as was the case for Brian at the very point when he’d had enough. Or the attention of a therapist who really gets where you’ve been and where you want to go, as was the case for Donna at the fulcrum of her despair. It

What will work best is whatever is available when the synaptic avenues of desire make contact with brain regions responsible for perspective change. This can be the presence of a friend who accompanies you to your first 12-step meeting, as was the case for Brian at the very point when he’d had enough. Or the attention of a therapist who really gets where you’ve been and where you want to go, as was the case for Donna at the fulcrum of her despair. It  can even be the horrific embrace of a jail cell where you see your options with brutal clarity, as was true for Natalie. (To read these hair-raising accounts in full, I’m afraid you’ll have to wait for the book.) It can be a month on your uncle’s farm, a book that captures your heart when you think you’ve lost it, or the stuck window opened by meditation, romance, or antidepressant therapy when you’ve been buried in your cave for too long a time.

can even be the horrific embrace of a jail cell where you see your options with brutal clarity, as was true for Natalie. (To read these hair-raising accounts in full, I’m afraid you’ll have to wait for the book.) It can be a month on your uncle’s farm, a book that captures your heart when you think you’ve lost it, or the stuck window opened by meditation, romance, or antidepressant therapy when you’ve been buried in your cave for too long a time.

Quitting requires a merger, perhaps a collision, between desire and perspective — again, what fires together wires together — yet it doesn’t demand any particular brand of intervention.

Nevertheless, next week I’ll describe a radical treatment initiative that I think exemplifies a right-minded approach to recovery. And I hope that, through your comments, you might also provide some ideas for how to awaken the treatment world.

……

Leave a Reply to Dr. Basim Elhabashy Cancel reply