Three posts ago, I discussed the personality traits that make us most vulnerable to addiction. And I promised to say more about them.

Most experts agree that the two biggees are….

(1) an impulsive or risk-taking personality style

(2) an anxious, oversensitive personality style

Note once again that there is nothing like a standard “addictive personality” — contrary to popular belief. In fact, these traits are almost perfect opposites. In her upcoming (excellent!) book, Maia Szalavitz emphasizes a third gateway: an insidious combination of the two. Maia says this was the recipe for her own addiction, and I think that was it for me as well. So let’s call this third personality pathway…

(3) an impulsive or risk-taking style combined with oversensitivity

How do each of these trait structures predispose us to addiction?

Most experts emphasize the link between impulsivity and addiction. That’s pretty straightforward, but it’s especially problematic in adolescence, when every kid gets somewhat impulsive (except for the real nerds) because evolution designed us that way. Now trait impulsivity becomes a risk factor for all sorts of things: shop-lifting, uprotected sex, preventable accidents, etc. But when you’re an impulsive person at an impulsive stage of life, you’re especially likely to hold out your hand when powders or pills get passed around. “Hey, I want to try that!” Drugs and booze are risky, and risk-takers are first in line.

Most experts emphasize the link between impulsivity and addiction. That’s pretty straightforward, but it’s especially problematic in adolescence, when every kid gets somewhat impulsive (except for the real nerds) because evolution designed us that way. Now trait impulsivity becomes a risk factor for all sorts of things: shop-lifting, uprotected sex, preventable accidents, etc. But when you’re an impulsive person at an impulsive stage of life, you’re especially likely to hold out your hand when powders or pills get passed around. “Hey, I want to try that!” Drugs and booze are risky, and risk-takers are first in line.

But there’s another, subtler, causal connection. Research links the impulsive/risk-taking trait package with inborn differences in the dopamine system, and this path to addiction was touted by Kenneth Blum as the reward deficiency syndrome. Due to normal genetic variability, some people have fewer or less sensitive dopamine receptors of a particular type (e.g., the D2 receptor in the nucleus accumbens, the brain region underlying reward seeking). According to Blum, these people need more dopamine to feel excited or engaged. I’ve written about this in detail elsewhere, but the idea is simple. If you need more dopamine to satisfy your underpopulated D2 receptor system, the easiest way to get it is to take drugs.

Now, if you know (maybe unconsciously) that you need more of a charge than others to feel good, then it makes sense to train yourself to seek and find risky situations. So, you may end up “hypersensitive” to high-impact rewards because that’s really what  you live for. People who are extreme in their impulsivity also lack normal levels of social anxiety. So they don’t care much about how others react to their excesses. Then we are verging on the antisocial/psychopathic personality style. And those people can be bad news in all kinds of ways.

you live for. People who are extreme in their impulsivity also lack normal levels of social anxiety. So they don’t care much about how others react to their excesses. Then we are verging on the antisocial/psychopathic personality style. And those people can be bad news in all kinds of ways.

What about the anxious, oversensitive person? We become anxious about how others react to us, sensitive to rejection, and perhaps obsessively concerned about how we are acting, not only based on genetic patterns (e.g., not enough serotonin) but also based on our family environment. If you are raised  by parents who are unpredictable, touchy, volatile, or anxious themselves, then you have every reason to become anxious in social situations — and a genetic blueprint that favours anxiety will help you get there. Why would such people be more likely to find drugs appealing and, eventually, addictive?

by parents who are unpredictable, touchy, volatile, or anxious themselves, then you have every reason to become anxious in social situations — and a genetic blueprint that favours anxiety will help you get there. Why would such people be more likely to find drugs appealing and, eventually, addictive?

I can speak to that personally. My mom was volatile and somewhat of a perfectionist. There was a lot of love between us, but I learned to worry about how I was behaving — and my behaviour was far from perfect. What looks like social anxiety from the outside can feel like self-criticism and self-doubt on the inside. That was me, and like many others who feel this way, it led me to depression even before I got to boarding school — where  I learned just how nasty life could get. Depression and anxiety are highly correlated with addiction for good reason: drugs make you feel different, either calmer or more uplifted, they give you the sense that you can control your mood by ingesting something, and you become less reliant on social approval because you’re standing right next to the feel-good tap. Particular drugs help (“self-medicate”) in particular ways. For me, it was the soothing caress of opiates; for others it can be the bright reassurance of meth or coke. For some, it’s both.

I learned just how nasty life could get. Depression and anxiety are highly correlated with addiction for good reason: drugs make you feel different, either calmer or more uplifted, they give you the sense that you can control your mood by ingesting something, and you become less reliant on social approval because you’re standing right next to the feel-good tap. Particular drugs help (“self-medicate”) in particular ways. For me, it was the soothing caress of opiates; for others it can be the bright reassurance of meth or coke. For some, it’s both.

What about #3, the combo? Maia Szalavitz speculates that being a risk-taker and an anxious perfectionist was the recipe for her addiction. Same with me. From the age of 3 or 4, I was the kid who would climb up the rose trellis and  stand on the roof, crowing. I was constantly cajoling my cousin, Nancy, to explore the ravine with me, though it was strictly off limits. To present my mom with the nicest possible bouquet, I picked every flower in our neighbour’s backyard. I slid down the ice slide right in front of my teacher, because I’d literally forgotten that she’d just told me never to do it again. That sent me on my first visit to the principal’s office — in Grade One! Then, as a teen, I wanted to try booze, and weed, as soon as they were offered. And I spent my last year of boarding school dreaming about our upcoming move to San Francisco, where the streets were said to be awash in LSD and other exciting chemicals.

stand on the roof, crowing. I was constantly cajoling my cousin, Nancy, to explore the ravine with me, though it was strictly off limits. To present my mom with the nicest possible bouquet, I picked every flower in our neighbour’s backyard. I slid down the ice slide right in front of my teacher, because I’d literally forgotten that she’d just told me never to do it again. That sent me on my first visit to the principal’s office — in Grade One! Then, as a teen, I wanted to try booze, and weed, as soon as they were offered. And I spent my last year of boarding school dreaming about our upcoming move to San Francisco, where the streets were said to be awash in LSD and other exciting chemicals.

But I think this is the most interesting part: my penchant for anxiety, depression, and self-criticism joined forces with a deeply rooted attraction to risk-taking. Take the pill, try the needle, why not? And then, wham! I suddenly feel like I’m the conductor of the symphony of my moods. Depression, be gone! With the help of my allies in the chemical kingdom, I’m the one in charge.

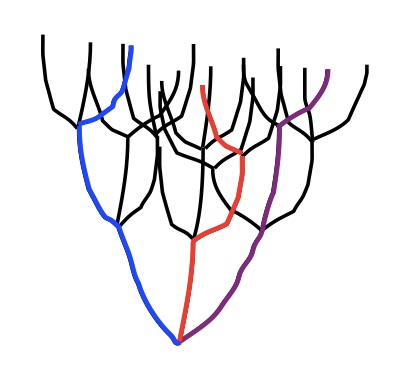

What this shows is that personality development brings divergent traits and proclivities to a point. Development takes the parts and welds them into a whole. And if that whole starts to coalesce around the attractions of substance use, there’s going to be a rough road ahead.

Leave a Reply to BobbyG Cancel reply