The talk I gave in Amsterdam had the title, “A Brain Disease or What?” This post is about the or what? But in attempting to define addiction, I come up with three words, rather than one:

The talk I gave in Amsterdam had the title, “A Brain Disease or What?” This post is about the or what? But in attempting to define addiction, I come up with three words, rather than one:

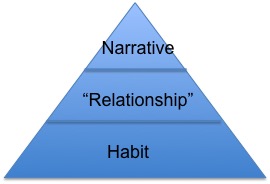

Habit

Relationship

Narrative

…and these words have to work together to explain what addiction is.

The idea that addiction is a deeply ingrained habit is relatively simple — at first. In fact that is the default definition generally posed against the disease definition. And habit is no stranger to the mind or the brain. We don’t reinvent our perceptions and

The idea that addiction is a deeply ingrained habit is relatively simple — at first. In fact that is the default definition generally posed against the disease definition. And habit is no stranger to the mind or the brain. We don’t reinvent our perceptions and  conceptions; we refine and consolidate them over time. And the brain works by creating circuits which are fundamentally self-reinforcing. It doesn’t seem much of a stretch to see addiction as a habit of seeking an expected reward and going through various motions to obtain it. It’s just that, with high motivation and endless repetition, this habit is deeply ingrained.

conceptions; we refine and consolidate them over time. And the brain works by creating circuits which are fundamentally self-reinforcing. It doesn’t seem much of a stretch to see addiction as a habit of seeking an expected reward and going through various motions to obtain it. It’s just that, with high motivation and endless repetition, this habit is deeply ingrained.

But many also see addiction as a relationship, for example between you and your drug, your beer, or your porn collection. That’s almost correct. Except that addiction isn’t a real relationship because it doesn’t consist of two interacting partners. The drug doesn’t adjust to you. You adjust to it. And adjust and adjust until the supposed relationship, in your mind, is locked in. So I’d say that addiction is the concept of a relationship.

That’s not special in itself. The study of child-parent relationships in mainstream psychology has mostly fallen under the banner of attachment theory. Attachment theory is all about the child’s concept of the relationship with, let’s say, the mother. A  secure attachment means the child expects the mother to be available when needed…emphasis on “expects.” An avoidant attachment means the child expects the mother to be unavailable. It’s not just mother’s behaviour that matters; attachment styles are predicated on child temperament as well as maternal behaviour. It’s children’s expectations that maintain their “attachment status” throughout life. An ambivalent or resistant attachment style means the child needs the mother excessively, expects disappointment, struggles against the need, and pushes away at the same time as pulling. Sound familiar? So if we think of addiction as a concept of a relationship (which I’ll call “relationship” in quotes), it seems to match an ambivalent/resistant attachment style. I want you, I need you, you’re not going to be there for me (about six hours later), you don’t help me enough, there’s no one else I can go to for the help I need.

secure attachment means the child expects the mother to be available when needed…emphasis on “expects.” An avoidant attachment means the child expects the mother to be unavailable. It’s not just mother’s behaviour that matters; attachment styles are predicated on child temperament as well as maternal behaviour. It’s children’s expectations that maintain their “attachment status” throughout life. An ambivalent or resistant attachment style means the child needs the mother excessively, expects disappointment, struggles against the need, and pushes away at the same time as pulling. Sound familiar? So if we think of addiction as a concept of a relationship (which I’ll call “relationship” in quotes), it seems to match an ambivalent/resistant attachment style. I want you, I need you, you’re not going to be there for me (about six hours later), you don’t help me enough, there’s no one else I can go to for the help I need.

Let’s put these first two elements, habit and “relationship,” together. “Relationships” are certainly habitual. They build on themselves over time. Many teenage or even adult children continue to berate their parents for not paying enough attention to them or not understanding them or not giving them enough, whether the parent does everything or nothing to change this conceptualization. And habits are relational. My habit of brushing my teeth involves a relationship with my toothbrush, and my dentist. So far so good.

Let’s put these first two elements, habit and “relationship,” together. “Relationships” are certainly habitual. They build on themselves over time. Many teenage or even adult children continue to berate their parents for not paying enough attention to them or not understanding them or not giving them enough, whether the parent does everything or nothing to change this conceptualization. And habits are relational. My habit of brushing my teeth involves a relationship with my toothbrush, and my dentist. So far so good.

Then what about narrative, the third element of the triad? I’ve written a fair bit about this, especially in the last chapter of my second book on addiction. We are constantly telling ourselves who we are, what we’re like, where we’ve been, where we’re going, etc. The life narrative is very much like what we might call our identity. It is not our personality — our underlying nature — but the way we construe ourselves. I’ve argued that changing one’s narrative is a potent way to move beyond addiction. I act like this because, Omigod, I was really suffering and this was the only solution I could find. So I’m not just a piece of shit; I’m a desperate seeker. But I don’t want to be doing this, and I don’t have to be doing this, and the future is changeable even if the past isn’t. The magical thing about narrative, or story, is that it is told. It doesn’t stay inside; it’s communicated with others, who can help us to hear it, hold onto it, reflect on it…and change it. Changing the narrative allows us to focus on the “relationship” more clearly, and to refashion beliefs about what that relationship entails, especially, what to expect. And it can change our habits, first by unearthing them, exposing them to the light, and then by a determined effort to choose B rather then A in situations we recognize as pivotal.

It may be that our narrative sits on top of our “relationship” (with what we’re addicted to) which rests on a set of habits. A hierarchy? I can see currents of change — deep change, “recovery” — moving down the hierarchy, from narrative to “relationship” to habit, or possibly up the hierarchy. Maybe both directions at the same time.

But there’s something huge missing from this analysis, and that is the role of compulsion. We have to go all the way back to habits and think about them again. Some habits, maybe most habits, are unconscious, and they trigger thoughts and behaviours before we can say “stop!” Compulsion is, for some, the defining feature of addiction. Next post, I’m going to look at how compulsion works and what to do about it.

But there’s something huge missing from this analysis, and that is the role of compulsion. We have to go all the way back to habits and think about them again. Some habits, maybe most habits, are unconscious, and they trigger thoughts and behaviours before we can say “stop!” Compulsion is, for some, the defining feature of addiction. Next post, I’m going to look at how compulsion works and what to do about it.

Leave a Reply to Chad Davis Cancel reply