Two posts ago I promised to follow up on “what is addiction?” by supplying the missing piece. Anyone who has experienced addiction or studied it knows that compulsion is that piece — the elephant in the living room.

Here’s a quick review:

A key aspect of addiction, as we experience it, is the urge to complete the act, scratch the itch, etc. You’ve probably heard a dozen phrases that try to capture that feeling, that moment. We know we’re not going to feel any better, maybe worse, or if we are going to feel better it won’t last long. We’ve gone through all the arguments and  counterarguments as to why we should not, cannot, do it one last time. We have done all we can to steer a path home that avoids the liquor store, to wait until our dealer is out, to provide a context that makes it unattractive or even impossible, like going to a meeting even. And then we lunge for it. The behavioural switch has been switched on — so it seems. And the alternatives and obstacles fade into the background. Just do it. Get it over with. There’s still 15 minutes before the liquor store closes. We can still find our dealer if we try.

counterarguments as to why we should not, cannot, do it one last time. We have done all we can to steer a path home that avoids the liquor store, to wait until our dealer is out, to provide a context that makes it unattractive or even impossible, like going to a meeting even. And then we lunge for it. The behavioural switch has been switched on — so it seems. And the alternatives and obstacles fade into the background. Just do it. Get it over with. There’s still 15 minutes before the liquor store closes. We can still find our dealer if we try.

This compulsive aspect of addiction arises over time. It’s not there for the first few weeks, or months, or maybe even years. And then it’s the main act. It’s the Achilles’ heal that resists every effort at mindful self-control. So it seems. And resisting the urge just wears us down — as per my descriptions of ego fatigue, in my book and other writings. The anxiety that mushrooms as we continue to resist becomes agonizing.

We can trace this psychological and behavioural sequence in ourselves or others. Both at the minute-by-minute scale — the way it builds over the course of an afternoon — and the month-by-month scale, the way it gets stronger the longer we continue using. But what’s going on with the brain in parallel?

The launching of an action (toward a goal) is governed by the striatum (or basal ganglia), a large structure with connections both “downward” to the amygdala and other parts important for emotion and “upward” to the prefrontal cortex, where expectations, plans and choices are activated. The striatum has a ventral (“southern”) terminal, which we often refer to as the nucleus accumbens. That’s considered the hot  spot for addictive cravings. But it’s also got a dorsal (“northern”) region. While the ventral striatum evokes anticipation, longing, and zeroing in on potential rewards (e.g., drugs, booze, porn), the dorsal striatum seems to be involved in automatic behaviours — what psychologists call Pavlovian conditioning, or stimulus-response (S-R) events.

spot for addictive cravings. But it’s also got a dorsal (“northern”) region. While the ventral striatum evokes anticipation, longing, and zeroing in on potential rewards (e.g., drugs, booze, porn), the dorsal striatum seems to be involved in automatic behaviours — what psychologists call Pavlovian conditioning, or stimulus-response (S-R) events.

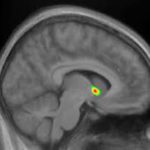

I’ve written about all this stuff previously, so I won’t get into more detail here. The main point is that only the ventral striatum (southern region: nucleus accumbens) becomes activated (bright yellow spots on the MRI) in early addiction — e.g., the first few months. But in later-stage addiction, activation increases in the dorsal striatum. For a while addiction neuroscientists thought that the addictive trigger got passed along, so to speak, from the ventral to the dorsal striatum. That could explain how addiction seems to evolve from being an active desire, motivated by an expected good feeling, to a habit, beyond conscious control and motivated by nothing at all — purely automatic. In fact, the disease model of addiction — the idea that drugs hijack the brain and destroy the will — got a lot of traction from this kind of neural model. See, folks, addiction means no more choice — it’s simply a compulsive act that can’t be stopped.

I’ve written about all this stuff previously, so I won’t get into more detail here. The main point is that only the ventral striatum (southern region: nucleus accumbens) becomes activated (bright yellow spots on the MRI) in early addiction — e.g., the first few months. But in later-stage addiction, activation increases in the dorsal striatum. For a while addiction neuroscientists thought that the addictive trigger got passed along, so to speak, from the ventral to the dorsal striatum. That could explain how addiction seems to evolve from being an active desire, motivated by an expected good feeling, to a habit, beyond conscious control and motivated by nothing at all — purely automatic. In fact, the disease model of addiction — the idea that drugs hijack the brain and destroy the will — got a lot of traction from this kind of neural model. See, folks, addiction means no more choice — it’s simply a compulsive act that can’t be stopped.

That turns out to be inaccurate. Recent studies, both with addicts and with those suffering from OCD (which has lots in common with addiction), show that the ventral hot spot, the nucleus accumbens, remains part of the flow of activity that moves us from a stimulus (a rumbling in the gut, a vodka ad, a

That turns out to be inaccurate. Recent studies, both with addicts and with those suffering from OCD (which has lots in common with addiction), show that the ventral hot spot, the nucleus accumbens, remains part of the flow of activity that moves us from a stimulus (a rumbling in the gut, a vodka ad, a  phone call from a buddy) to a response. The response. The data suggest that the ventral and dorsal striatum both get involved in the kind of compulsive actions that characterize addiction. But they seem to take up different phases of the moment-to-moment sequence, with the dorsal striatum staying active longer, holding the action “at ready” until it’s executed, and the ventral striatum contributing to the earlier phase, the blush of wanting and seeking.

phone call from a buddy) to a response. The response. The data suggest that the ventral and dorsal striatum both get involved in the kind of compulsive actions that characterize addiction. But they seem to take up different phases of the moment-to-moment sequence, with the dorsal striatum staying active longer, holding the action “at ready” until it’s executed, and the ventral striatum contributing to the earlier phase, the blush of wanting and seeking.

So the habitual nature of addiction is nothing like the habit of wiping your hands on a napkin or brushing your teeth. It’s not automatic in the same way. Addictive urges are far more complex. Even after years of addiction, those compulsive moments are packaged together with an emotional surge, a bouquet of emotions that are probably both positive and negative, a conscious sense of moving toward an expected reward, AND, finally, a more automatic sense of “must.”

What’s the point?

If the compulsive aspect of addiction remains part of a conscious stream of anticipation and preparation, then we have far more choice than we might have thought. Choice and will don’t just disappear with years of use.

Certainly the compulsive “just do it” urge increases over time, both over months and years and over minutes and hours. But the compulsion never replaces the impulse, the wish, the want, the conscious anticipation that we associate with the nucleus accumbens. Rather, the compulsion might be the final springboard to action, coming at the tail end of a series of thoughts and feelings that are conscious — and therefore controllable.

Leave a Reply to jeremy thompson Cancel reply